If there is one topic that is not – or very little – talked about in Luxembourg, it is the over-indebtedness of private individuals. The strength of the country’s internationally recognized financial centre, the growth rate of its GDP, its renowned lofty salaries and high quality of life can be deceiving: few are those who expect over-indebtedness to be more than a marginal topic, let alone a real societal issue.

However, an important share of Luxembourg households is considered indebted (54.6% in 2014), and their median debt value is particularly high (89,800€ in 2014 versus 73,400€ in 2010). The Information and Counsel Service for Over-Indebtedness (SICS) registers several hundred requests for support each year; nearly 550 support requests were received by the Ligue Médico-Sociale and the asbl Inter-Actions in 2017. According to a study led in Luxembourg by the CEPS (Center for the study of Populations, Povery and Socio-Economic Politics), in 2008 3% of households were overindebted. This number rises to 4.1% when credit card expenses that could not be reimbursed within the last three months are accounted for.

More recently, the Luxembourg Central Bank, which regularly undertakes studies on the over-indebtedness of households in the Grand-Duchy, was raising the alarm on the question of the sustainability of debt. It notably highlights that young and unemployed households are more exposed to the risk of over-indebtedness, and that compared to neighbouring eurozone countries, Luxembourgish households appear strongly indebted in absolute terms. This difference can easily be explained: the high cost of living, particularly of real estate, is a driving factor. In 2013, over 38% of Luxembourgish households held mortgage debt, against 23% across the eurozone. In a ranking of 326 cities worldwide, the Luxembourg capital is in 37th position, amongst the most expensive cities.

"This topic raises high financial stakes, but also ones of societal responsibility for these organisations"

It remains complicated to obtain more global and representative data to better apprehend the scope of tis issue in the Grand-Duchy. The numbers on household over-indebtedness provide an idea of the debt of individuals, but doesn’t really inform about the situations of over-indebtedness per se. Similarly, the data supplied by the SICS only represent a visible minority of cases, because people affected by over-indebtedness seldom turn to these services, out of shame or denial about their situation.

Over-indebtedness is thus a genuine reality affecting a wide range of stakeholders. Banks and credit intermediaries are not the only organisations confronted with this issue. Even though the financial sector is involved in the first instance, private employers, actors in the field of professional insertion, service providers (telephone, energy…), as well as the socio-medical ecosystem are also actively concerned. This topic raises high financial stakes, but also ones of societal responsibility for these organisations.

A multidimensional reality

What does over-indebtedness really mean? In Europe, there is currently no consensus around a common definition, which notably explains the difficulty to measure this phenomenon at the supranational level: each country has its own indicators and legislation on the topic. In Luxembourg, the state of over-indebtedness is characterised in the law by the “undeniable impossibility for the debtor domiciliated in the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg to meet the whole of their professional debts due or falling due”.

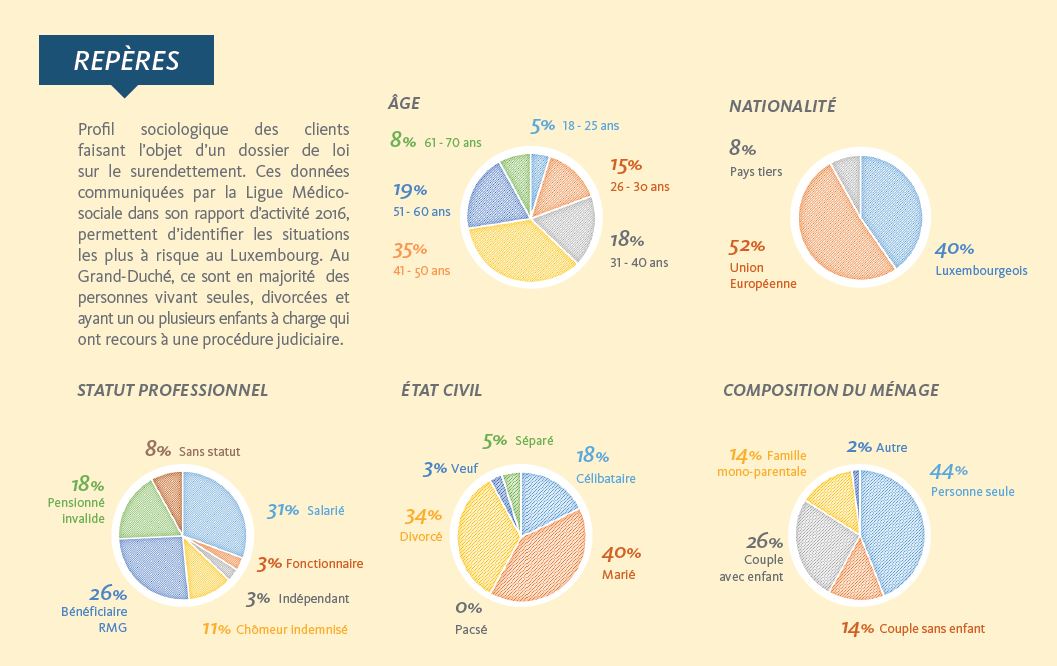

At first sight, there is a tendency to represent a stereotypical image of the over-indebted individual: an unemployed person reaching his rights-end, a single stay-at-home mother, a father overwhelmed by gambling debts. However, whilst these situations can exist, they do not represent the diversity of situations, and are little more than clichés.

Here, it is important to distinguish the difference between active and passive over-indebtedness. The former is the result of the accumulation of loans (mortgage, car loans, consumer loans…) which will, after reaching a certain threshold, lead to the incapacity to cover all reimbursements. On the contrary, passive over-indebtedness arises from a life accident and the loss of a stable income. This potentially affects all swathes of population and the factors can be varied: illness, job loss, retirement.

Thus, there is no single representation of the overindebted person, but a multitude of situations. This is illustrated by the 2016 beneficiaries of Crésus, France’s federation of associations fighting over-indebtedness: 58% were employees, against only 11% of unemployed persons and 6% of beneficiaries of the lowest welfare income (minimas sociaux).

Unexpected consequences

Social and familial isolation, deterioration of mental health, addiction, the suicide of close relatives, the loss of a job, limited access to health care/terms one would not immediately associate with the problem of over-indebtedness. Nonetheless, the latter’s consequences on individuals are manifold and can lead to tragic situations. Indeed, in France, every day 3 people resort to suicide because they can no longer repay their loans. Over-indebtedness and financial difficulties are thus the cause of a quarter of all suicides.

David McDaid, expert from the London School of Economics, affirms that “over-indebtedness multiplies the chances of developing depression, anxiety and obsessive compulsory disorders”. This can easily be explained: the pressure exerted by creditors and bailiffs, whether over the phone or by mail, reinforces the daily anxiety caused by an almost permanent state of poverty. Feelings of guilt and shame add to this precarious emotional state, impacting social ties and contacts with family and loved ones. The over-indebted individual, in addition to grappling with financial difficulties, thus ends up in a state of permanent isolation, low self-esteem and anxiety.

Did you know?

More than 13 million Europeans are unable to pay off their loans.

(Eurobarometer, 2005)

Corporations are implicated

Beyond its dramatic human consequences, over-indebtedness entails important economic and financial costs for companies. As an employer, an organisation ought to think about those of its employees who might be struggling with financial difficulties. An over-indebted employee is likely to miss more workdays, and the stress induced by his/her situation can affect his/her productivity at work. The human resources departments are directly affected, for instance when creditors resort to wage withholding.

For Nancy Marinelli, social worker at Arcelor Mittal’s Health and Work department in Luxembourg, over-indebtedness thus accounts for 30% of her workload. She attests that “this spiral does not only affect those less well off, but also employees and executives whose financial balance was upset”.

Moreover, over-indebtedness issues generate categories of financially vulnerable clienteles. Banks, but also service providers (telephone, energy…) are constantly exposed to unpaid bills and must set up debt collection services. In Europe, payment delays amount to 90 billion euros and represent 10.8 billion euros in lost interests every year. In Luxembourg, over 1000 companies went bankrupt in 2013; amongst them, 20% were caused by payment delays and defaults. This phenomenon particularly impacts small and very small ventures. In France, yearly unpaid debt averaging 56 billion euros (2% of the country’s GDP) are reversed in the losses and profits accounts of French companies.

What about the rest of Europe?

Over-indebtedness does not equitably affect all European countries. Indeed, within the EU, no legal text defines common regulation about credit institutions or the handling of over-indebtedness cases. Some statistics do however exist, allowing us to gauge the situation at the European level. As such, according to a 2005 Eurobarometer, 13% of households across EU member states struggled to face the reimbursement of their credits and other commitments. Similarly, we now know that over 13 million European citizens cannot meet their debt.

Amongst the most affected countries, Denmark must be mentioned, as its household debt reaches 300% of revenues; but also the United Kingdom, where credit regulation is more permissive than in other states. In the latter, the “payday loans” thus emerged, granting short-term loans used to make ends meet, often accessible on the internet and with interest rates reaching 100%. The consequences are disastrous: in the United Kingdom, 1 in 6 Britons can no longer reimburse his/her debt and household indebtedness has reached unprecedented heights (127 million euros in 2012). These frightening figures keep climbing, not without recalling the pre-2008 situation: the current trajectory tends toward similar debt to GDP ratio observed in the years preceding the financial crash. The question of a new bubble arises, built on student loans, all-time high consumers credit and mortgages and threatened by the perspective of Brexit and its associated economic and financial implications.

Whilst Luxembourg is not spared by over-indebtedness, it is not confronted with the ravages raging in other, less prosperous European states. The country is thus still able to anticipate and act to keep the problem in check: to do so, it needs to further develop financial education, provide means to improve prevention mechanisms and raise awareness across the population, unravelling the taboo around the over-indebtedness issue.

Student debt, a critical issue across the Atlantic

Amongst all stakes linked to the problem of over-indebtedness, that of student debt is scaling up, especially in the United States where the load of student loans is a serious concern. Over 1,000 billion US dollars of student debt burden 44 million American citizens, as 70% of students finish their studies with important loans to repay. The figures rose sharply throughout the last decade (+145%), not without consequences. In a recent study surveying 3000 American students, 39% considered dropping out to avoid additional debt. In 2015 and 2016, almost 4 million students left university with debt and without a degree, exposing themselves to higher risk of unemployment (+2 points) and lower salaries (-35%).

Assistance from the federal government was rolled out, notably under the Obama administration which launched the “Student Loans Forgiveness Program” or “Pay as you earn Program”. It allows students to reimburse their loans according to their revenues, as opposed to at a fixed monthly rate; it also allows debt to be erased after 20 or 25 years. This system is however criticized for only benefitting the middle and upper classes. The individuals most exposed to financial difficulties, usually only borrowing smaller amounts of money, would not be the main beneficiaries of this aid.

Student debt, a critical issue across the Atlantic

Amongst all stakes linked to the problem of over-indebtedness, that of student debt is scaling up, especially in the United States where the load of student loans is a serious concern. Over 1,000 billion US dollars of student debt burden 44 million American citizens, as 70% of students finish their studies with important loans to repay. The figures rose sharply throughout the last decade (+145%), not without consequences. In a recent study surveying 3000 American students, 39% considered dropping out to avoid additional debt. In 2015 and 2016, almost 4 million students left university with debt and without a degree, exposing themselves to higher risk of unemployment (+2 points) and lower salaries (-35%).

Assistance from the federal government was rolled out, notably under the Obama administration which launched the “Student Loans Forgiveness Program” or “Pay as you earn Program”. It allows students to reimburse their loans according to their revenues, as opposed to at a fixed monthly rate; it also allows debt to be erased after 20 or 25 years. This system is however criticized for only benefitting the middle and upper classes. The individuals most exposed to financial difficulties, usually only borrowing smaller amounts of money, would not be the main beneficiaries of this aid.

To be read also in the dossier "Lives on Credit":