Growing Uncertainties

Being an insurer means mastering risk, anticipating it to be better prepared. With climate change, or should we say climate disruption, the equation has never been so complex. Last year, there were no fewer than 274 disasters and 81 billion dollars worth of damage attributable to these extreme events. How is the sector, which is more central than ever, coping with this new situation?

Extreme weather events are skyrocketing and so is the damage

The weather events in various parts of Europe this summer were striking in their magnitude. July, in particular, was the second hottest month ever recorded on the continent. As a result, major forest fires broke out in Turkey, Greece, Portugal and France. In addition, heavy rainfall hit northern Europe and parts of Italy, causing deadly floods. These two types of events are, it should be remembered, the result of global warming, which, as scientists point out, also greatly disturbs the water cycle.

In Belgium and Germany, more than 200 people lost their lives and the damage is estimated at several billion euros. In Belgium alone, the bill already amounts to two billion euros and is likely to increase further, as some reconstruction costs have yet to be assessed. Here in Luxembourg, the Grand Duchy was heavily affected in July. Fortunately without making any victims, the torrential rains caused no less than 6 500 homes and 1 300 cars to be damaged, with damage estimated at 125 million euros. A record in the history of Luxembourg insurance.

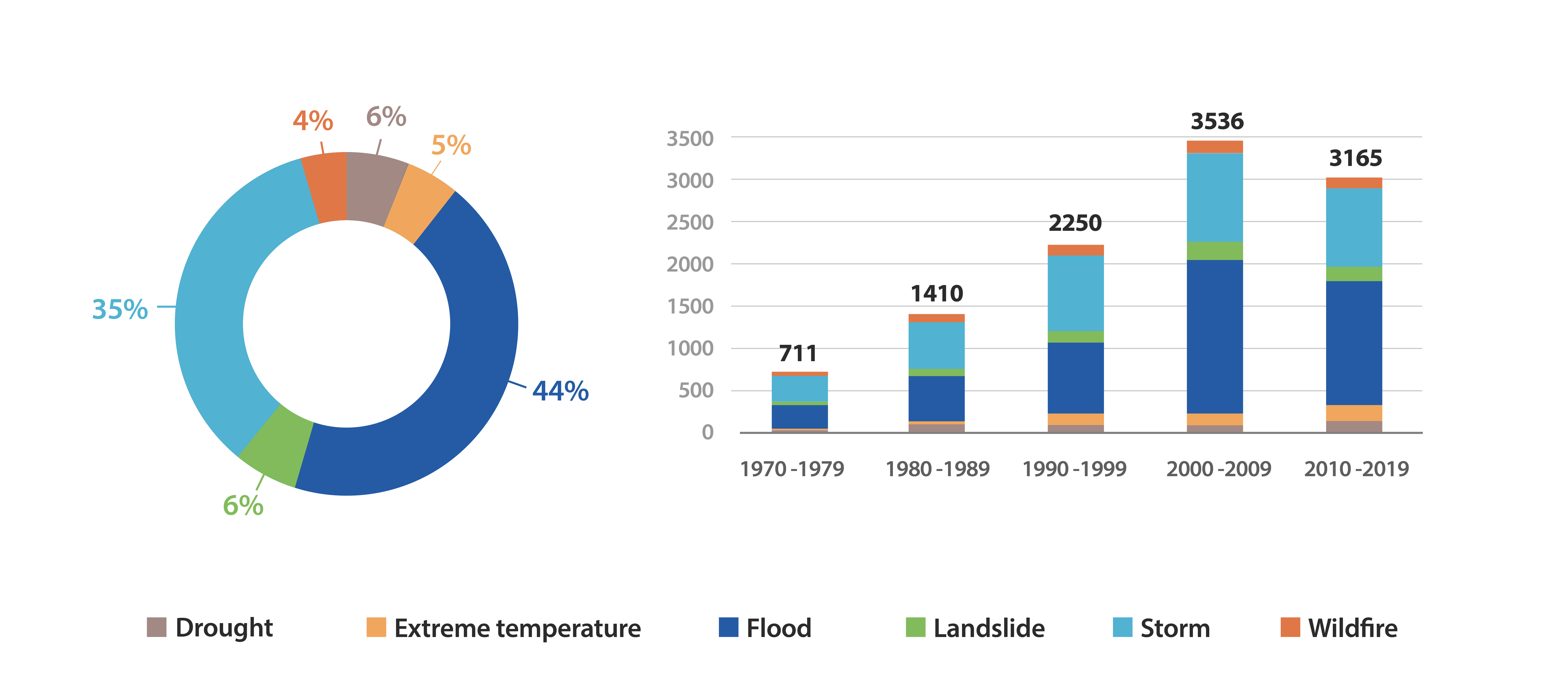

This summer is just one of the markers of a major trend. The meteorological manifestations of climate change continue to strike with greater frequency and intensity: cold spells, torrential rain, storms, droughts leading to uncontrollable forest fires, etc. The scale of the damage is, year after year, ever greater. According to the World Meteorological Organization, meteorological events caused economic losses of 1,381 billion dollars over the period 2010-2019, compared with 942 billion between 2000 and 2009 and 852 billion over the period 1990-1999.

It is storms and related events that are adding to the bill. According to Swiss Re, over the period 2011-2020, storms cost insurance companies 218 billion dollars worldwide. In comparison, floods generated 67 billion in losses. It should be noted, however, that floods remain the main source of disbursements in Europe with 20 billion dollars against 16 billion for storms.

Swiss Re's latest Sigma report found 174 natural disasters in 2020 alone, causing nearly 8,000 deaths and 190 billion dollars in economic losses. A dark year, marked by Australia fighting unprecedented fires, America facing a record hurricane season, the American Midwest devastated by a powerful "derecho" phenomenon, massive monsoons in Asia and the overflow of the Yangtze River, the second most costly flood on the continent. In total, the sums insured have reached 81 billion dollars and the trend is set to continue.

Evolution of climate disasters and their economic impacts

Climate change is changing the way risk is managed

Unsurprisingly, climate change is resulting in increased risks for the insurance business. The sector approaches climate risk more precisely through the following three parameters: geophysical and hydrometeorological hazard, exposure and vulnerability.

Geophysical and hydro-meteorological hazard is the probability of an extreme natural event such as a storm or forest fire. It is constantly increasing as climate change becomes more apparent. Indeed, the occurrence of natural disasters has never been as high as it has been since the 2000s.

Exposure is defined as the quantity of assets exposed at a given time, such as buildings or vehicles. Rapid urbanisation is a major factor in increased exposure to risk. Mapping helps to highlight this development. In California, the city of San Diego has experienced an urban expansion of more than 800% over 60 years and, whereas in the 1940s fires did not reach any dwellings, more than 5,000 were destroyed over the decade 2000-2010. Overall, Swiss Re estimates that urbanisation will account for 10% of the increase in property insurance premiums by 2040.

Vulnerability is the final element taken into account by an insurer to assess risk. It is the sensitivity of an asset to a climatic event, to be affected by it. In order to assess this criterion, it is necessary to take into account the characteristics of the asset, such as the quality of a building for example, the shape of its roof, or to cross-reference it with its exposure by assessing its geographical location (close to a river that often floods...).

The risks linked to natural events are constantly increasing and it is changes in the three parameters mentioned above that are the cause. Indeed, the multiplication of extreme climatic events, combined with urbanisation and the artificialisation of land over ever larger areas, lead to an increase in the number of claims. These combined effects, reinforced by, in some cases, an increase in the population (sometimes very significant, as is the case in the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg where, according to Statec figures, the population has grown by 74% since 1980), lead to an ever greater disbursement of assets covered by insurance companies.

So one risk can hide another. In addition to direct damage, there are also secondary risks linked to extreme weather events: forest fires can spread particles to neighbouring towns and have an impact on the health of the inhabitants. A flood can cause damage to critical infrastructures such as medical or IT structures, etc., triggering other risks. This intricacy is increasingly studied by the sector and, as the head of the Axa Group's foresight department points out, "climate change is undoubtedly the matrix of other risks".

New technologies for insuring climate risk

Insurers are refining their risk management and models using the latest technology. Data analysis is central to risk assessment and the triggering of claims and can now be collected quickly. The increased use of sensing devices such as drones or satellites allows for more accurate and real-time data transmission. Thanks to this data, new insurance products are being marketed. Among them, parametric insurance, although it has existed for about twenty years, is developing particularly thanks to the use of new Earth Observation technologies. This generation of insurance makes it possible to automatically trigger compensation in the event of the occurrence of an event, on the basis of exceeding a contractually predefined threshold. This avoids the sometimes very long process of estimating the damage, often based on the intervention of experts, which applies in the context of 'classic' property insurance. In concrete terms, in the example of a fishing village in Asia affected by a hurricane, the monitoring tools inform the insurer almost in real time if certain rainfall levels have been exceeded. (If this is the case, the insurer immediately pays out the expected amount to the insured, in an objective manner, regardless of the damage suffered. This type of product addresses the problem of making the money available quickly so that those affected can get back on their feet without delay after a disaster.

Towards more prevention

A risk that does not materialise is obviously the ultimate goal. The work of an insurer therefore includes prevention, in the interest of the insured and the company itself. Using the data collected, insurers work to prevent the risk before it occurs. For example, new warning systems can alert policyholders to the possibility of an extreme weather event and provide them with preventive advice on their health and property. New Earth Observation technologies are also used here. Using historical data to anticipate rainfall and temperature trends, an insurer can, for example, recommend that a farmer adapt his plantations to climate change or choose a particular roof shape that is more resistant to weather conditions. Munich Re, for its part, has developed an application to assess exposure to climate risks by cross-referencing the location of the insured property with the various scenarios developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). In the field, some insurers such as Zurich finance flood prevention programmes through awareness campaigns, raising the height of houses, etc. Even further upstream, Axa has chosen to opt for solutions based on nature by financing the reforestation of mangroves which protect against flood risks.

The social issue behind the increase in premiums

The sharp increase in climate risk raises a major question: that of the increase in premiums, or even the difficulty of insuring certain more vulnerable territories or types of risk. In its latest report, Swiss Re estimates that weather events will increase the risk for property insurance by 33-41%, generating 149 to 183 billion dollars in new premiums. "We expect that in advanced markets, an increase in the frequency and severity of natural catastrophe events will add 30-63% to insured catastrophe losses. In some key markets such as China, the UK, France and Germany, the increase could reach 90-120%," the reinsurer warns. This observation is confirmed by the French banking and insurance supervisory authority ACPR which, at the end of its 2020 climate pilot exercise, points to the expected increase in claims and insurance premiums: "Throughout France, climate change would imply an increase in claims linked to natural disasters of 2 to 5 times for the most affected departments and premiums would increase by 130 to 200% over 30 years to cover these losses.

This forecast raises questions about the acceptability of the traditional insurance model in the face of such a price surge. Such a prospect leaves one pensive when one knows that, at the global level, the disadvantaged populations are hit hard by these risks and will find it financially impossible to insure themselves.

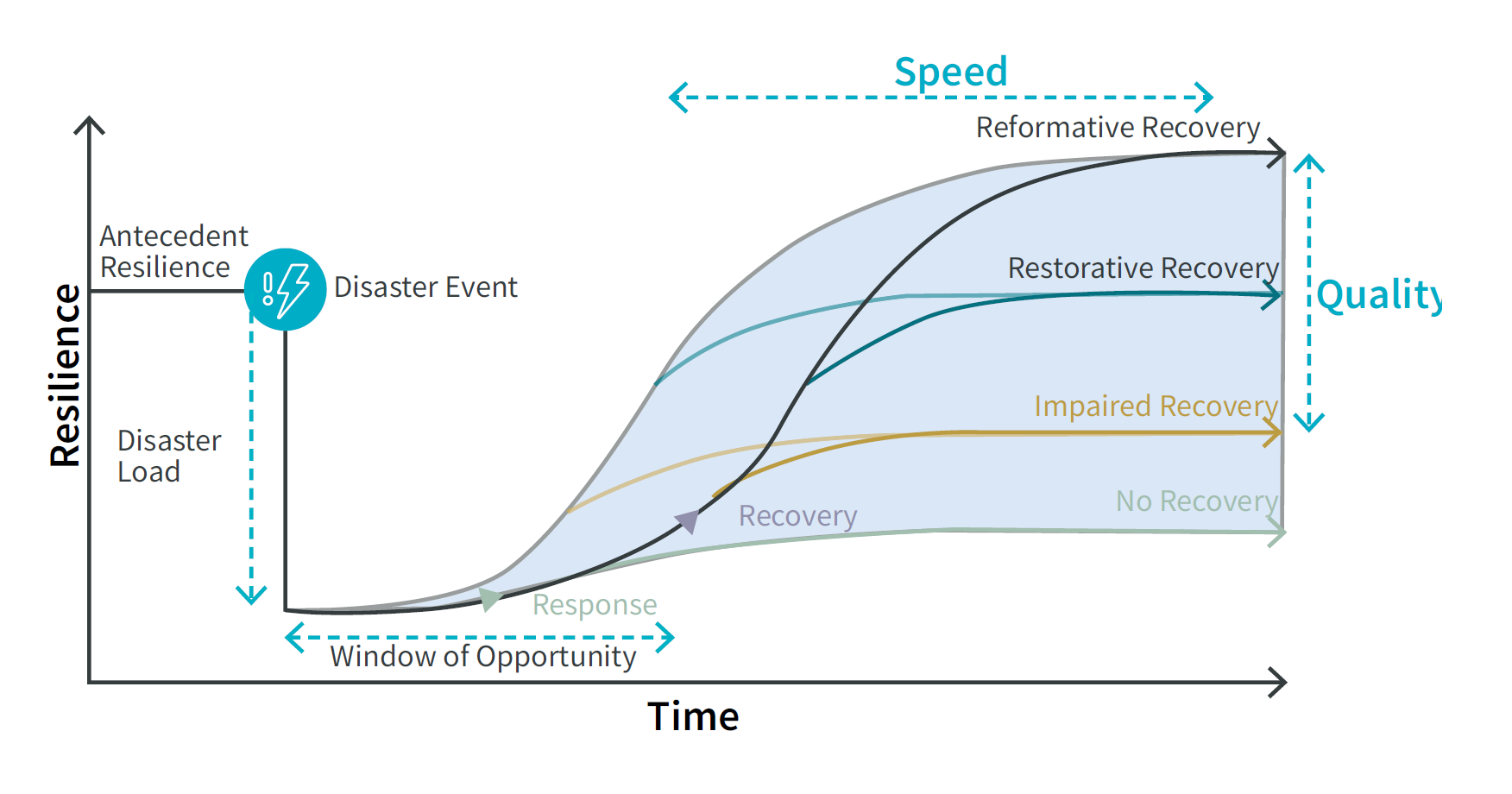

However, the role of insurance is key to a territory's ability to bounce back after a major shock such as an extreme climatic event. It is crucial for the affected populations to be compensated as quickly as possible in order to hope for a return to their previous socio-economic level. This is what a joint study by the Centre for Risk Studies in Cambridge and Axa XL highlights: the speed and quality of a territory's recovery after a major natural disaster is strongly conditioned by its level of insurance coverage. Countries with better coverage, such as Japan, Australia or Western Europe, wait on average less than a year before seeing their territory return to the level before the shock. They often even take advantage of this to rebuild better, allowing for a stronger recovery. Those, such as Bangladesh, Nepal or the Philippines, will have to wait more than four years and will generally not return to pre-disaster levels. A telling example is the comparison between the 2010 earthquake, from which Haiti has still not recovered, and the floods that hit Germany in 2013, affecting 600,000 people with 80,000 displaced, following which the country managed to recover economically and socially within a year.

As the graph below illustrates, an insurance system that allows for rapid disbursement of funds is crucial to the resilience of a territory.

The speed of the intervention as well as the quality of the aid makes it possible to hope for a rapid return to the previous situation, or even to overcome the disaster.

The insurance sector has a very strong societal role here, as the entire economic fabric is at stake. Faced with the increase in climate risk, the difficulty of certain market players to insure regions that are too exposed and the corollary increase in premiums that is expected, the industry is at a turning point and must question its model. It is essential not to drive people away from insurance and thus precipitate a rise in social and economic insecurity. The fundamental question of solidarity in the face of climatic risks has never been so acutely asked.

In some countries, funds exist to deal with natural disasters. This is the case in Belgium, for example, where a disaster fund is paid into at regional level by all insured persons. In Luxembourg, specific aid is provided for people or companies affected by these events: the Solidarity Division of the Ministry of Family, Integration and the Greater Region and the Ministry of the Economy are responsible for their respective areas. In France, a natural disaster compensation mechanism, 'catnat', instituted by the legislator in 1982 following the 1981 floods, responds to this problem of lack of coverage. Despite this, the delays in compensation can be long and throw families into precariousness and this risk pooling model is far from being generalised to all countries.

Insurers are now calling for more public-private partnerships in order to offer the widest possible coverage at affordable prices. This is why some initiatives, at the state level or between countries, are being launched to address these issues. The SEADRIF (SouthEast Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility) initiative is one such initiative. Launched by some countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), in partnership with the World Bank, SEADRIF offers a platform to prepare for and respond to natural disasters in the countries concerned: flood risk modelling, parametric insurance, regional reconstruction capacity, etc. The association proposes a series of solutions and prevention methods to minimise the risks and consequences of natural disasters.

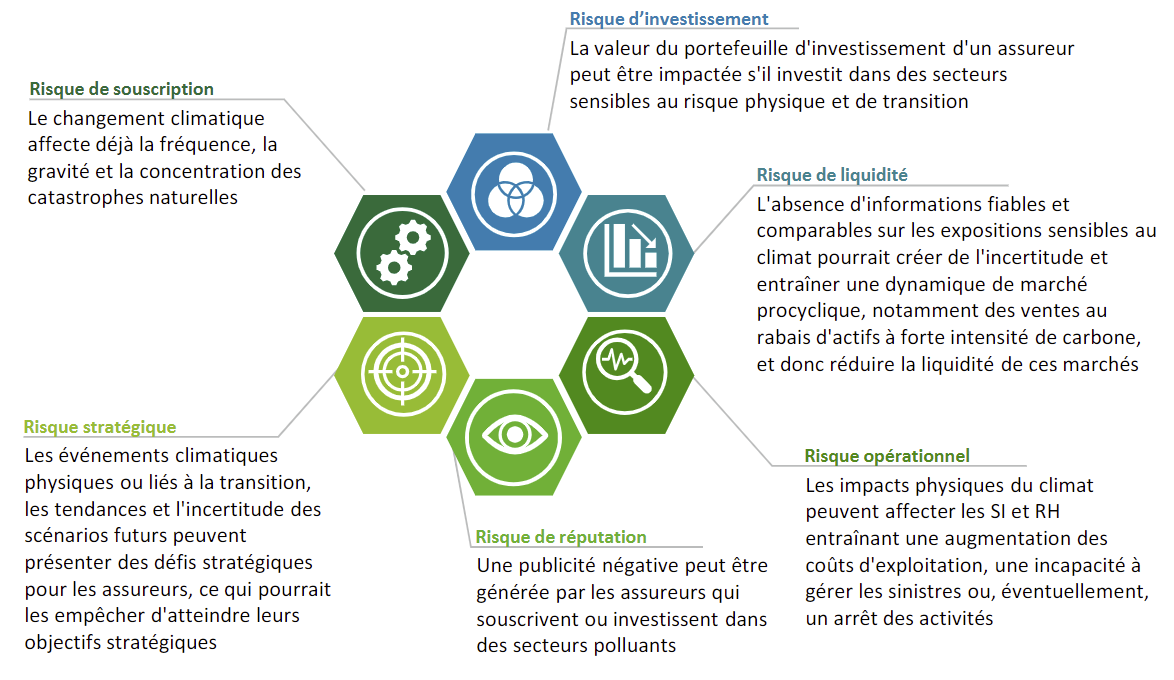

Beyond the underwriting risk, insurers are exposed on all sides by climate change

The physical risk is the risk of damage that is directly linked to the natural disaster, leading to compensation, as mentioned above. In addition to this direct exposure (underwriting risk), insurers are impacted at different levels. This is what the audit and consulting firm Deloitte identifies in its publication "Climate risk: understanding it in practice in insurance" of May 2021. It points out that the multiplicity and importance of claims can lead to operational risk through increased operating costs. It also highlights a strategic risk, due to the uncertainty of achieving objectives. There is also a reputational risk through negative publicity against insurers who do not take a sufficiently responsible environmental approach. This can even lead to a legal risk if commitments are not met.

Finally, the transition to a decarbonised model, if it is to be rapid or if it is not sufficiently anticipated, can lead to liquidity risk in the event of a massive resale of carbon-intensive assets.

A risk particularly observed during the COP26 discussions is the investment risk. This is because each insurer invests the premiums received in different financial assets, including equities, debt securities and other forms of finance. These investments are sensitive to physical risk, of course, but also to so-called transition risk. As defined by the Luxembourg Central Bank in its 2021 "Financial Stability Review", transition risk refers to "the potential impacts on financial stability of a rapid or abrupt transition to a less carbon-intensive economy in order to limit the impacts of climate change. This transition may be accelerated by regulatory or legislative changes, technological developments, but also consumer preferences and social pressure.

As a result, insurers, like other financial market players, are increasingly scrutinised for their ability to anticipate but also to promote the transition through investment choices that are in line with their commitment to environmental responsibility.

Climate change impacts all risks

A role in accelerating the transition to a more sustainable world

The best prevention is to attack the roots of the climate problem by encouraging the transition to low-carbon activities and, more generally, to activities with no negative environmental impact. Insurers, with trillions of dollars in premiums collected worldwide (6,287 billion dollars in 2020), have a role to play through their financial investment policies. Collectively, they represent an important lever for redirecting flows towards a more sustainable economy, in line with the Paris Agreement. Today, a portion of these investments is unfortunately still invested in carbon assets, but initiatives are showing a strong shift in this area. Numerous insurers such as Aegon, Allianz, Munich Re and Zurich have joined a group of 43 investors gathered around an initiative under the auspices of the United Nations Environment Programme, the Net-Zero Asset Owner Alliance. With a portfolio of 6.6 trillion dollars in assets, these companies are committed to decarbonising their investment portfolio by 2050. They are adopting a strict approach based on the Science-based Targets method, including intermediate targets for 2025.

In the run-up to COP26, insurers have reaffirmed their intention to accelerate their transition and to protect nature more effectively. Allianz, for example, announced that it has partnered with the International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, to promote climate-smart investments aligned with the goals of the Paris Agreement in emerging markets. For its part, Axa has announced its intention to invest 1.5 billion euros to support sustainable forest management. The company has also announced that it will not make any new direct investments in listed equities and corporate bonds in developed markets in oil and gas companies operating in the so-called "upstream" sub-sectors (i.e. the exploration and extraction part and all related activities).

To accelerate the transition, industry players are also committing to their underwriting policies. Eight of the world's largest insurers and reinsurers, in partnership with the United Nations, have come together in the Net-Zero Insurance Alliance (NZIA). They are committed to moving their individual underwriting portfolios towards net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050, within a maximum temperature increase of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels by 2100. For example, more than 30 insurance companies are now refusing to insure mining operations, making it much more difficult to operate a coal mine.

By reforming their underwriting and investment policies, insurers can make a difference. The change must be rapid and effective if it is to achieve a drastic reduction in greenhouse gas emissions. Faced with the magnitude of the climate challenge and the uncertainties of a world facing multiple crises, the sector is seeing its role strengthened more than ever, but also its model widely challenged. Today, it is undertaking an in-depth reform. Quickly enough?