A Strategy that Hits the Target!

Updated on February 15, 2026

What connection can there be, between a fly depicted at the bottom of an urinal and a Nobel Prize in Economics? Indeed, the link is indeed not clear…

But if we add that this trick – which was launched for the first time in the nineties at the Schiphol airport in the Netherlands – enabled a reduction of more than 70% in cleaning costs, it becomes clearer.

Since then the fake flies inspired others and have become more popular in toilets of many public places across the globe as well as in Luxembourg. The example can make you smile, but these effective solutions at a very low cost are not trivial and men are far from being the only potential target…But what exactly is it about? Behavioural suggestion, marketing trick, benevolent manipulation, soft incentive? A little bit all at the same time: we speak more generally of “nudges”, a word that draws upon our natural irrationality in terms of choice. Human beings see their decisions affected by heuristics (thought processes built upon our emotions, the environment or the context to take extremely quick decisions) which create “cognitive biases” when they dysfunction. For instance our brains tend to prefer immediate satisfaction over long-term well-being. It’s the short-term valuation bias that in particular allows to explain that many people say they are in favour of defending the ecology without changing their consumption or sorting habits. But, there are many others: the social norm, the search for conformity, risk aversion, the availability bias (tendency to value recent examples or events in the press or in our lives). All in all, over 185 biases have been identified to date. As many tracks to explore to stimulate civic-mindedness, cleanliness or interest for the planet.

At the crossroads between behavioural economics and cognitive psychology, the nudge has been popularized thanks to two American researchers, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, with their publication “Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth and Happiness” published in 2008. The authors establish the principle that indirect suggestions can have a greater impact than constraints. That is what they call the “libertarian paternalism”. Paternalism because the individuals’ choices are guided towards decisions that benefit the community, libertarian because free will is not violated.

The nudge’s strength lies thus in its capacity to generate an action without any regulatory or moralizing rhetoric. It allows to swing naturally from intent to action. Therefore a windfall! In particular for public institutions in their attempts to encourage respect for the environment, better health or civic-mindedness such as seen at the Schiphol airport. The examples are as numerous as they are diverse. In 2011, the Stockholm metro for instance transformed the stairs of one station into a giant piano to encourage users to exercise a little. The result: the curious users abandoned the escalators to listen to the music under their feet!

"The nudge’s strength lies thus in its capacity to generate an action without any regulatory or moralizing rhetoric. It allows to swing naturally from intent to action"

A few musical steps for a little work out in Stockholm.

A nudge at the service of sustainable development or green nudge can also be an efficient and "soft" tool when the transition from good intentions to ecological actions turns out to be complex. For instance, placing green footprints on the floor heading for municipal bins, has proved to be efficient in many cases with a decrease of up to 50% of waste thrown on the ground nearby. Similarly, the American city La Verne (California) is known for having succeeded in improving their waste sorting by telling every resident on a daily basis the amount of sorting carried out by other residents. In the same way, some hotel chains succeeded in limiting overconsumption as well as unnecessary laundry cleaning by indicating in the rooms messages like: “75% of the people having occupied this room before you, used their towels several times”. In many situations, referring to other people’s behaviour refers back to the social norm and turns out to be more efficient than simple calls for the preservation of water or the environment. And the results are not long in coming! David Halpern, Director of the Behavioural Insights Team, explains that electricity bills that introduce an element of comparison with "virtuous" neighbours lead to consumption reductions of 2 to 4%, a result that could only be achieved otherwise with a 20% increase in electricity prices. Thaler and Sunstein clarify in their reference work “a desirable behaviour can be encouraged, at least to a certain extent, if the public’s attention is drawn to what the others do”.

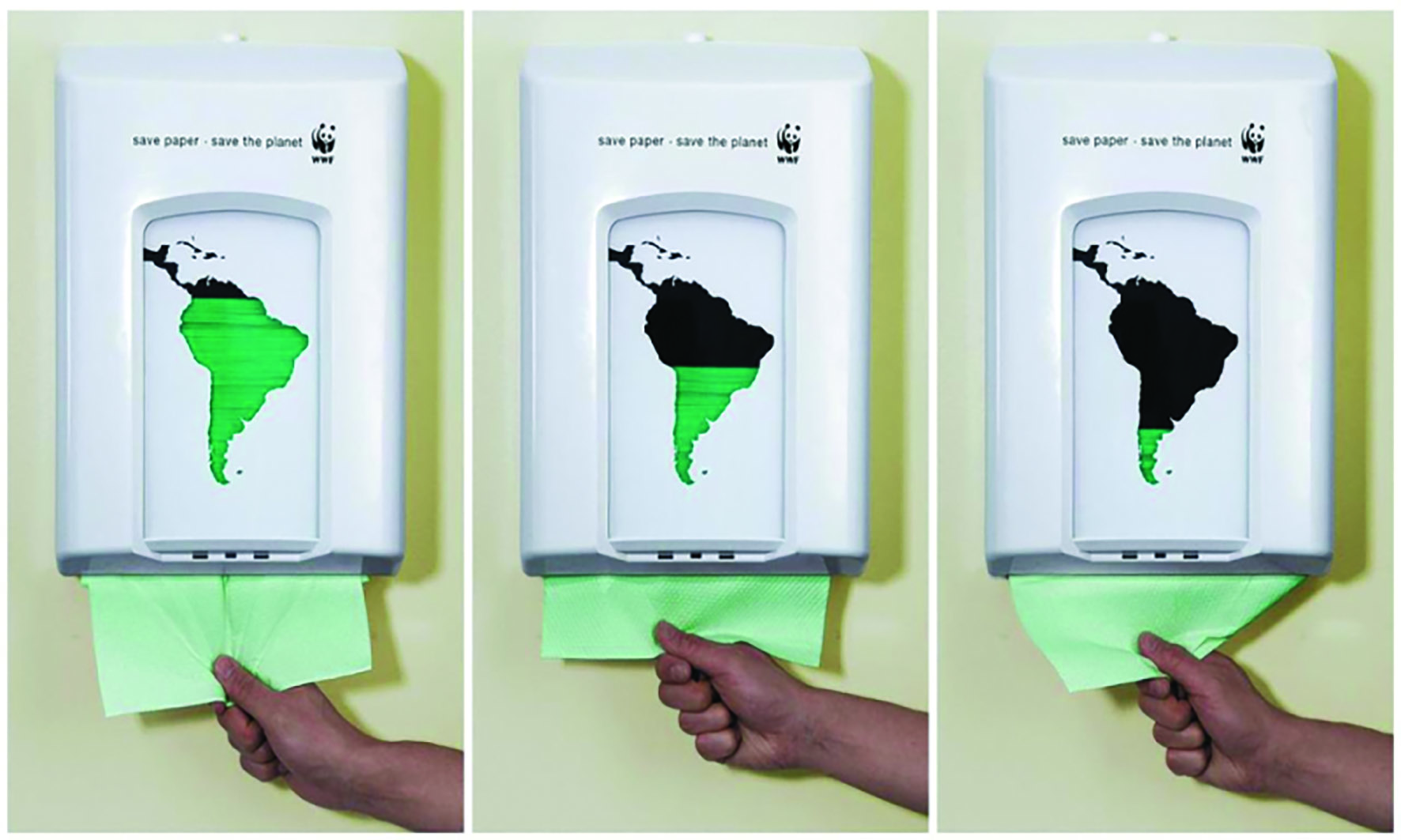

Credit: WWF

Green Nudge, an efficient tool used by WWF in its campaign "Save paper, save the planet".

Among enlightened managers and other heads of marketing, this piece of advice hasn’t fallen on deaf ears opening up new horizons to pack away the carrot and the stick and use indirect incentives (called “marketing nudge”). For example, many online booking sites are using this trick by “innocently” ensuring competition between each other. “6 people are currently watching this offer”, “establishment booked 28 times in the last 24 hours”, “last booked one hour ago” … These push us, admittedly with a little help, but this time towards our credit card…

Such a strategy can raise ethical questions in particular on the definition of the “desirable behaviour”, and the possibility to provide false or made up data with the sole aim to urge consumers in a given direction. For some, this is a form of citizen manipulation that the end can never justify.

The nudge’s evil twin : the sludge !

Eric Singler, chief executive of the research and consultancy firm BVA, in charge of the "nudge unit" defends the nudge’s strong deontological dimension and underlines its need to be based on transparency and co-construction. The nudge complies with ethical principles that are inherent to its efficiency: its goal is to encourage positive behaviours without constraining or limiting the available options and it doesn’t in any case draw on the non-deliberative faculties of the individual (for instance appealing to impulses)

“With great power comes great responsibility”: like the mantra that reads the fate of young Peter Parker, alias Spider-Man, the use of the nudge presents ethical as well as political challenges and obligations. Therefore be careful, misusing the insights from behavioural economics and thus creating “sludges” can work in the very short-term as any mass manipulation or arbitrary constraint; but, turns out to be counterproductive over time. Indeed, this leads to a loss of user confidence towards a product, a brand or a management style which is difficult to redress. Internally, forcing overconformity will invariably harm team creativity and work commitment.

The nudge’s evil twin : the sludge !

Eric Singler, chief executive of the research and consultancy firm BVA, in charge of the "nudge unit" defends the nudge’s strong deontological dimension and underlines its need to be based on transparency and co-construction. The nudge complies with ethical principles that are inherent to its efficiency: its goal is to encourage positive behaviours without constraining or limiting the available options and it doesn’t in any case draw on the non-deliberative faculties of the individual (for instance appealing to impulses)

“With great power comes great responsibility”: like the mantra that reads the fate of young Peter Parker, alias Spider-Man, the use of the nudge presents ethical as well as political challenges and obligations. Therefore be careful, misusing the insights from behavioural economics and thus creating “sludges” can work in the very short-term as any mass manipulation or arbitrary constraint; but, turns out to be counterproductive over time. Indeed, this leads to a loss of user confidence towards a product, a brand or a management style which is difficult to redress. Internally, forcing overconformity will invariably harm team creativity and work commitment.

In Luxembourg, the examples are quite uncommon for now, but one in particular has been noticed by football fans during the 2018 World Cup. The Service Hygiène (Sanitation Department) of the city, in the framework of its “anti-littering” campaign, has installed its first ballot bin or voting bin at the Champ du Glacis to encourage visitors to participate in maintaining the cleanliness of the site. The voting bin which has been popularized in the United Kingdom is an urn-shaped ashtray, equipped with two separate compartments allowing to answer a question by throwing in cigarette butts. Visible and fun, the ashtray stimulates smokers to show civic-mindedness and allows non-smokers to visually follow the survey’s progress. Once the urn is full, the city services just have to empty it and potentially can change its question. When we know that one cigarette butt alone can pollute 500 litres of water and take 15 years to totally degrade we do better understand what is at stake.

The success of said ashtrays – there was an overall decrease of about 30% of cigarette butts on the floor – encouraged the city to mainstream the initiative during the 2018 Schueberfouer and thereafter at the city’s main bus stops. In total twelve voting bins are now placed in the city and 18 more could be placed soon at key busy sites. “Besides the conventional means of communication, we wanted to use more innovative awareness raising actions, by taking care of not moralizing, while getting people to reflect on what they do and change their behaviour” tells Gilles Rob, manager of the General Services Environment – Sanitation Department of the City of Luxembourg. The questions are regularly changed and the city has even been asked by non-smokers whether it was possible for them to participate in the voting. The voting bin is a good example of how nudges can be used to influence without rushing the behaviour and to produce positive results when conventional methods have proven to be little efficient.

In Luxembourg, messages are multiplying to avoid cigarette butts on the floor. What is coral? / Do cats have milk teeth? / How do bees communicate?

Thaler’s work on behavioural economics earned him the Nobel Prize in Economics in 2017 "for having inserted psychologically realistic assumptions in the analysis of the economic decision-making process”. The loop is closed. Thaler explored and verified experimentally many cases where the rationality of our decisions is challenged in particular in our way of consuming. For Richard Thaler, this Nobel Prize was a sort of “moral reward” having more value than any other prize. The first comment of the lucky winner on the pretty penny that goes with the prize was: “I will try to spend it in the most irrational way possible”!

Also to be read in the dossier "Nudge":