Walter Stahel: The origin of “cradle-to-cradle”

“The circular economy has been omnipresent in society, but it is silent and invisible”

INTERVIEW

Sustainability MAG: Back in the 1970’, you coined the term “cradle to cradle” and are since recognized as a pioneer in the field of circular economy. What key conceptual change did you want to introduce?

Walter Stahel: In 1973, I joined the Battelle research centres in Geneva; 1973 was the year of the oil price shock, which led to rising unemployment in Europe. It occurred to me that the economy should use the plentiful and economise the rare resources, by substituting manpower for energy. From my work as an architect, I knew that refurbishing buildings needs more labour, earns the architect higher fees and results in cheaper housing than demolishing and rebuilding. It also creates much less construction waste and needs considerably fewer resources, as the load bearing structure – accounting for 80 percent of the embodied resources – is mostly preserved.

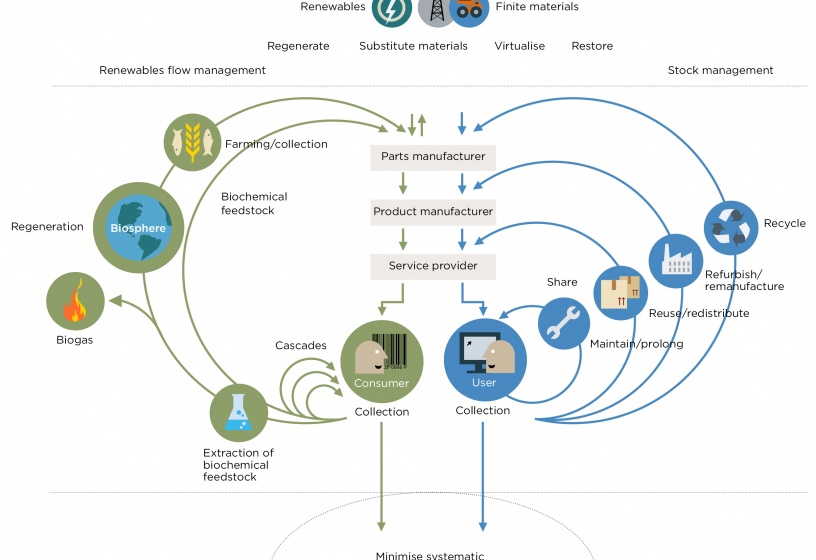

I suspected that this substitution of manpower for energy was also true for other industrial sectors and submitted a research proposal on “the potential for substituting manpower for energy” to the then Commission of the European Communities in Brussels, to verify this hypotheses for the French automotive and building sectors. The resulting 1976 report by Genevieve Reday and me fully confirmed my thesis and detailed the vision of an economy in loops, today called circular economy, and its impact on job creation, economic competitiveness, resource savings and waste prevention. In 1981, I published the report in the USA as a book under the title of “Jobs for Tomorrow”.

In the early 1980s, policymakers involved in waste policies put forward the idea of a product responsibility “from cradle to grave”. I pointed out that “cradle to grave” is simply a marketing upgrade for gravediggers, because it still relies on end-of-pipe solutions, and insisted that the really sustainable solution was to use durable goods in a loop economy from “cradle back to cradle” in order to prevent waste. In 1989, German experts unsuccessfully tried to block my study on “Long-life goods and recycling – waste prevention strategies for products” for the Ministry of the Environment of Baden-Württemberg, upholding that waste prevention was only possible by recycling waste in manufacturing processes, not in product utilisation. This shows how revolutionary my 1976 report to the European Commission had been.

Only in 2016 – forty years after my research – a Swedish politician and a Stockholm professor of economics undertook to verify the societal, macroeconomic impact of a shift to a circular economy. Using an extended Input/Output model, they analysed a dozen European countries and found in each case a substantial reduction of CO2 emissions by about 65% as well as an increase in employment of about 4% – a clear substitution of manpower for energy also on national level.

When it comes to the loop economy, the benefits in terms of environmental impact are first understood. However, you place a particular emphasis on the social aspect…

My conceptual change was to study the utilisation of stocks in a regional economy, while economics is concerned with the optimisation of manufacturing flows up to the point of sale. Analysing the utilisation of stocks enabled me to “discover” that a circular economy uses more and skilled local labour and less energy, produces less CO2 emissions and results in less expensive objects than manufacturing; the environmental benefits and resource savings were a broad and welcome consequential benefit, but not the driver of my quest.

Today, the benefits of the circular economy in terms of a reduced environmental impact stand in the limelight because we have not made real progress in reducing waste volumes, nor resource depletion or greenhouse gas emissions. Neither have we reached full employment in most industrialised countries; in the era of Industry 4.0 and ageing populations, the circular economy offers opportunities for silver workers to use their skills and knowledge in preserving existing stocks and values through the service-life extension of existing systems and objects.

For industrialised Western countries, the remaining circular economy challenge is to achieve zero waste by doing away with “mixed waste” and “secondary resources”, through technologies to recycle atoms and molecules of purity comparable to virgin resources. The knowledge of de-polymerising plastic polymers, de-vulcanising rubber goods, de-linking metal alloys could be the basis of the mining sector of the future. A vast potential for job creation.

You underline the necessary shift to a “performance economy”. Why should companies change?

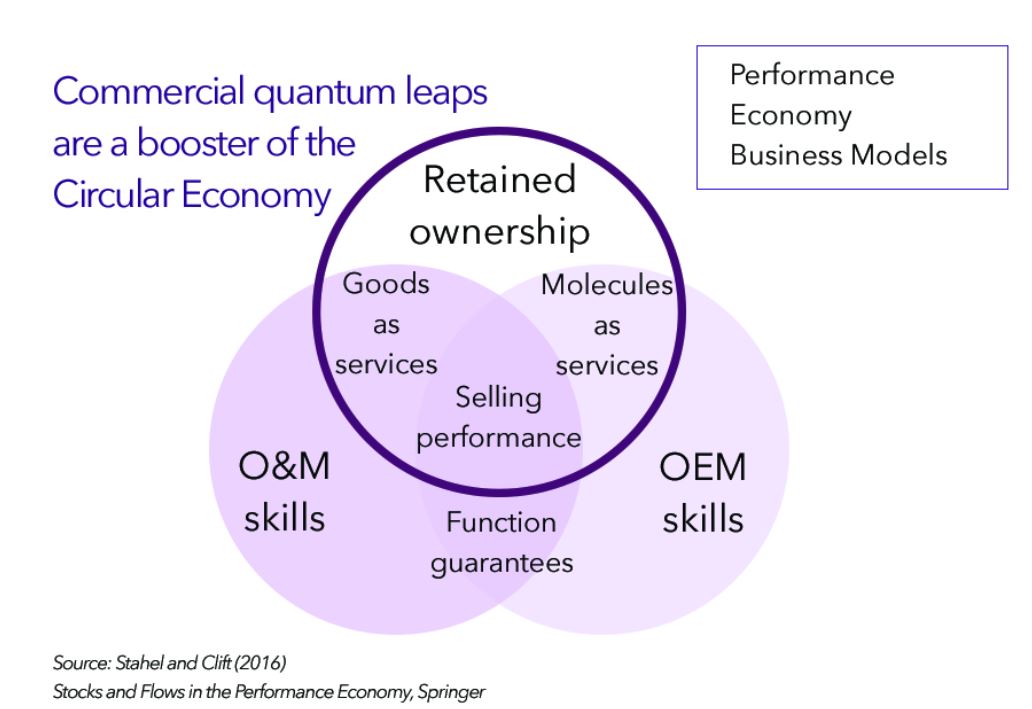

Because the performance economy is the most competitive and sustainable form of a circular economy. By retaining the ownership of their products over the full service-life, economic actors internalise the liability and costs of risk and waste, which gives them strong financial incentives to prevent losses and waste in order to increase profits.

One incentive to change is competitiveness: compliance and transaction costs of buying resources – both virgin and post-recycling – are constantly increasing as new regulations and legislations are adopted by a number of national and international bodies. Think of conflict minerals, water rights, child labour and environmental impairment in mining and recycling activities. As retained ownership eliminates most of these compliance and transaction costs, the competitiveness of the business models of the Performance Economy will continuously increase over time, but escapes simple cost-benefit comparisons between manufacturing and leasing/rental strategies.

Another incentive is future resource security: if a company retains the ownership of its products, including the embodied resources, the goods of today are the resources of tomorrow at yesterday’s commodity prices. It can remanufacture and upgrade the existing stock of goods, or have it recycled to recover the materials. If the prices of materials go up, the company may have a considerable cost advantage over competitors relying on the purchase of new resources.

However, providing performance as a qualitative service over the longest possible period of time with the least material and energy input demands “re-thinking” corporate strategies in a holistic way.

Precisely on this point, how can companies embark on this journey?

By exploiting synergies between sufficiency, efficiency and systems solutions in the use of existing stocks of goods and their embodied resources, in combination with socio-techno-commercial innovation.

Companies exploiting the business models of the performance economy need to master at least two of the following three capabilities: original equipment manufacturing (OEM) skills, operation and maintenance (O&M) skills, and retained ownership (see figure). Traditional OEM and marketing excellence will not suffice. The key is innovation.

Do you have in mind instructive examples in this area?

Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) are a proactive strategy to finance public infrastructure without public funds, based on the pay-for-use principle (tolls). The “Viaduc de Millau”, for example, is the result of a 78-year contract, signed in 2001 to design, finance, build the toll bridge and operate it until 2079, without any costs to the French state, including a maintenance contract which runs until 2121. The bridge was designed and built in three years – 250 meters above the river – using a novel construction method, which also aims to minimise operation and maintenance costs.

Public procurement demand to buy performance will increase as nation states recognise their financial and intellectual limits and rely more on sustainable innovation from start-ups. The birth of Space X and its reusable Falcon 9 rocket, which is able to land on the launch pad from where it has taken off, is a direct result of NASA’s change in procurement policy. A few years before the end of its space shuttle programme, NASA decided to buy only commercial launch services instead of hardware, specifying the mission unique requirements.

Recently, the performance economy has been pushed to new peaks by the Internet of Things (IoT), where most profits come from exploiting the function and use of goods, not their manufacturing. Guaranteeing the performance of objects over time will maintain corporate revenue streams and profits, but a new set of skills will be needed.

This new model marks the rise of profusers, as you call them...

Precisely. “Profusers”, or Profound-Users, are owners managing their physical stocks or capitals to maintain their value, and thus key actors of the circular lake economy. “Profusers” can be individuals or companies with a profound resolve and knowledge to make objects last through caring and appropriate operation and maintenance skills. No manufacturer produces objects that last 100 years, but innumerable objects of this age—from buildings to vehicles—exist, courtesy of individual profusers. Similarly, and coming back to the NASA, their space shuttle system was not built to operate for 33 years, but NASA, its public owner-manager, or profuser, made it last that long.

Hundred years ago, the norm was owners repairing – or having repaired – their goods, many maintaining themselves cars, houses and household items. During eras of abundance, this knowledge faded away but can be reactivated. Technical, even planned obsolescence can be overcome by inventions and the sharing of knowledge, skills and tools. New commercial firms and social forums, such as www.iFix.com and repair cafés in Europe and Australia, empower profusers to a degree which had ceased to exist in industrialised countries.

“Profusion” is a term for lasting wealth, plethora, capital, treasure. I have used profusion to express the sustainability in a circular lake economy, which preserves the quantity and quality of stocks. Profusers pursue similar objectives to fleet managers selling objects-as-a-service; the difference is that profusers are normally owner-users, such as collectors of vintage vehicles, whereas fleet managers are owner-operators, such as railways, airlines, serving customers.

Such an economic model supposes that this new “product-as-a-service” offer concomitantly meets a new demand. Are you confident that consumers will rapidly change their habits?

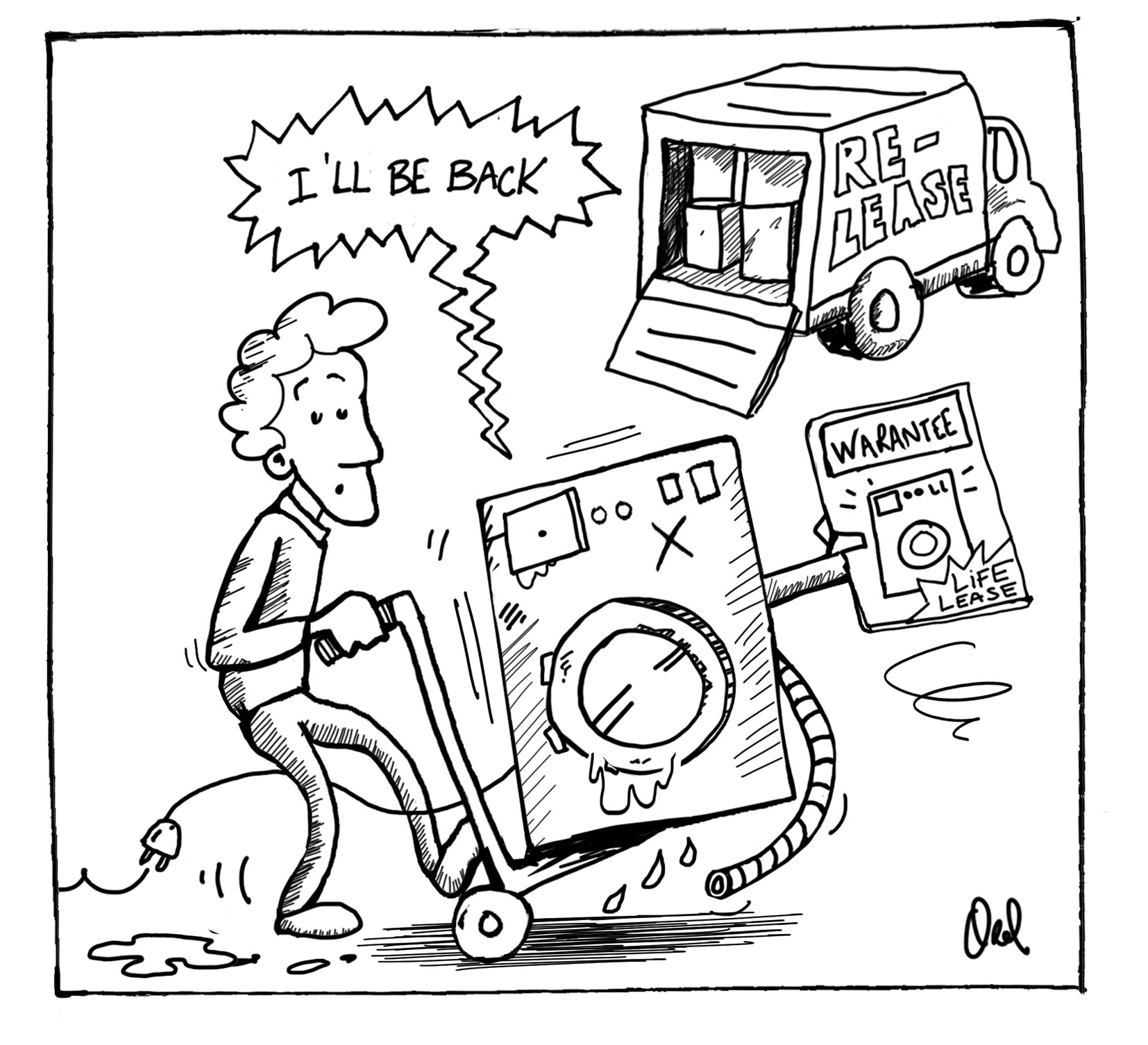

I foresee a drastic change in consumers habits in our industrialised societies. Buying objects which increase in value makes sense for individuals, buying objects which rapidly lose their value does not. Buying a house makes sense over time, buying a washing machine may not. Objects-as-a-service turn consumers into users, give them a great flexibility in use and open sufficiency options.

Besides, manufacturers and fleet managers selling goods-as-a-service can technologically upgrade the goods in use or adapt them to changes in fashion rapidly, even more so if upgrades can be done digitally. Witness computer software. The “time-to-market” for innovations in a performance economy is thus drastically reduced compared to replacement sales. This option would also be open for objects sold to customers, if they were designed accordingly – but is it in the interest of manufacturers? Microchips for instance could be designed for reprogramming, which could drastically reduce WEEE waste volumes and increase the profitability of chipmakers selling the chips-as-a-service, but at the same time negatively impact the sales of hardware manufacturers.

Illustration: Aurélien Mayer

One of the key recommendations featured in the Third Industrial Revolution study recently conducted in Luxembourg is the implementation of a new taxation system. Such a measure would follow the internalization of costs associated with externalities and favour the shift to a circular model. You are yourself calling for a “sustainable taxation”. Can you explain the benefits of such a measure?

The three reasons to promote sustainable taxation are inherent in the nature of human capital, of the circular economy and the importance of caring to promote a sustainable society.

The Circular Economy is about managing stocks or capitals, assets: natural (including biodiversity and bioeconomy), human (people and skills), cultural (both physical and intangible), manufactured capital (the circular industrial economy) and financial.

Of the stocks listed, the natural and human capitals are the only renewable resources; but human capital is the only one with a qualitative component. If people cannot use their capabilities and skills in the labour market, these are lost and people become unemployed, eventually unemployable. The perishable qualitative component of human capital gives governments a moral obligation as well as a self-interest to promote the use of human capital before any other resource.

By nature, the circular industrial economy substitutes manpower for energy and preserves the value of stocks and embodied CO2-emissions, so policymakers can promote it by adapting the framework conditions accordingly: do not tax renewable resources including human labour, but tax loss of natural stocks, waste and emissions instead (taxation as if human labour mattered); levy Value Added Tax (VAT) only on value-added activities (the value preserving activities of the circular economy should be exempt); give carbon credits to emission prevention, for instance through reuse and service-life extension activities, to the same degree as to emission reduction measures.

Caring activities are labour intensive, be they looking after human, natural, cultural or manufactured capital. They include education and training, healthcare and caring for the elderly and handicapped, clearing dead biomass in forests to reduce the risks of wildfires, cleaning drainage pipes to reduce flood risks; decontaminate natural assets (rivers, lakes and oceans), looking after cultural heritage, including technology and science artefacts in museums or also maintaining the value of, and technologically upgrading, manufactured objects (infrastructure, buildings, technical systems and goods).

Not taxing work – human labour – will foster, and reduce the costs of, all caring activities, many of which are the responsibility of, and paid for by, Nation States. Abolishing taxes on labour would allow paying lower salaries without reducing net income and welfare. The first European country to adopt this logic is Sweden; at the end of 2016, the Swedish Parliament passed a law which reduces VAT on repairs to 12%, from 25%, and allows individuals to deduct the labour costs on repair from their income. On 2 February 2017, the EU commissioner in charge of taxation has called on member states to push forward with shifting taxes from labour to natural resources, carbon and energy, which is a radical change; but as taxation is a privilege of EU member states, the European Commission can only motivate national governments to act.

What do you think are the prospects for circular economy at a worldwide level?

There is an issue of discontinuity which lacks understanding. Less industrialised countries are ruled by a circular economy of scarcity and poverty, by necessity. In industrialised countries with saturated markets – when the number of new goods coming to market is comparable to the number of similar goods going to waste – the circular industrial economy is by choice to cope with abundance and to reduce waste. We are missing strategies which enable us to shift from a circular economy of scarcity to one of abundance, without passing through a consumer society based on emotions and fashion and its waste problems.

China, India, Africa, South America are some of the major regions facing this issue. India, for example, relied for decades on shared public transport and a car industry based on two models, Ambassadors and Fiat 1100, which at the end of their lives were returned to the factories for remanufacturing, technological upgrading and remarketing. With the arrival of domestically produced modern cars, emotions and fashion have replaced function and scarcity. The car manufacturers’ responsibility ends at the point of sale; nobody is in charge of optimising the systems solution of infrastructure, cars and human health; India is faced with constantly increasing volumes of vehicles, air pollution and end-of-service-life car waste. Hindustan Motors, (re)manufacturer of the Ambassador, closed down in 2016.

At the same time, people in European countries, faced with problems of saturation, increasingly give up car ownership in favour of car sharing and public transport, renouncing emotions and fashion for function and efficiency.

As you just stressed, it seems like the circular economy principles are now gaining momentum in our industrialized countries. Do you look to the future with optimism?

Of course, “the future is where I intend to spend the rest of my life”, to quote Einstein, and I think it will be bright, because the champions of the circular economy are many. There are hundreds of reuse champions, but we don’t recognize them as being part of the circular economy, such as second-hand markets including auction houses and eBay, and antique dealers who “buy junk and sell antiques”.

The champions of repair are the innumerable SMEs maintaining equipment, vehicles, goods, garments, infrastructure and buildings, but also non-commercial formatself-help groups in the sharing society, such as hundreds of repair cafés and dedicated websites.

Champions of reuse and remanufacture are the aviation and the vehicle industry as well as the actors of the Performance Economy selling goods as services. These include service industries and the virtual economy, manufacturers like Xerox and Caterpillar as well as fleet managers, such as airlines and shipping lines, armed forces, taxis and hotels.

The economic and technical knowledge and know-how of the circular economy clearly exists in SMEs and fleet managers; the challenge is to transfer this wisdom into all classrooms and boardrooms in order speed up the transition from a throughput to a circular and performance economy. Countries which succeed in doing this rapidly will take the lead in sustainable competitiveness. Industrial sectors which succeed in combining the preservation of existing stocks with quantum leaps in technology and science will become industrial leaders. Political leadership will accelerate the transition from the present to the future without sinking the ship.

Maybe I am less optimistic about sharing and caring as the basis of a sustainable society, where abuse leads to developments like the Tragedy of the Commons. Society needs ethics for sharing values and punishment for abuse, needs to find a holistic path that allows all to benefit from the digital revolution and democracy while integrating Big Data and Artificial Intelligence.

In the virtual world of Internet, social networks, smart phones, wearable IT and ultimately the ‘Internet of Things (IoT), everyone has become a producer of data, e.g. through wearable and driveable electronic devices, the data of which are gathered by global giants like Google, Apple or Amazon and commercialised in the global ‘Big Data’ markets. Where are the dwarfs to contain the new Gullivers? Toffler’s “ prosumer” has reached a dimension, which its inventor probably never imagined, but in which authorship and property rights, basically protected through national laws, are mostly ignored. Policymakers so far have not come to grips, neither with the prosumer (producer-consumer) of the digital nor the profuser (profound-user) of the physical world. Yet understanding how they can contribute to a more sustainable society may be key to our sustainable future.

Walter Stahel

is a Swiss architect, graduated from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zürich. Founder and Director of the Product-Life Institute Geneva, he is the author of The Performance Economy and, with Orio Giarini, of The Limits to Certainty, facing risks in the new Service Economy.

To be read also in the dossier " Circular Economy: Closing Loops":