Interview with Naomi Oreskes

"We need to keep a vigilant eye on the desinformation game"

In this captivating interview, Naomi Oreskes, historian of science and professor at Harvard, insists on the urgency of understanding the mechanisms of disinformation at play in our society. The deliberate instillation of doubt by some industries poses a major obstacle to the essential collective actions such as the fight against global warming.

Interview

Sustainability Mag : Naomi, your academic career began as a historian of science, but then you delved into a truly distinctive research field, agnotology. Could you tell us more about this research field?

Naomi Oreskes : Agnotology is the study of ignorance and how it is socially constructed and perpetuated. My journey into this field began during my research into the history of oceanography. I stumbled upon scientists who had been studying climate change since the 1950s, uncovering a rich history of climate research that had been mostly overlooked. What truly stroke me was the wealth of scientific evidence supporting climate change, far more substantial than what was portrayed in early 2000s American media. This incongruity between scientific knowledge and public perception piqued my interest and led me deeper into the realm of agnotology. I realised that understanding how ignorance is manufactured and manipulated is just as critical as advancing scientific discoveries.

In essence, I embarked on a journey to uncover the roots of societal ignorance and its impact on crucial issues like climate change.

That's a fascinating journey indeed. In your best-selling book, "Merchants of Doubt" (2010), you've shed light on how corporations manipulate science to foster ignorance. Could you provide insight into how science is wielded to cultivate ignorance in society?

Certainly. "Merchants of Doubt" delves deep into this troubling phenomenon, revealing various instances where science has been misused or misrepresented to sow the seeds of doubt. We explore pivotal moments from the 1970s, '80s, and '90s when scientists were forming a consensus on several critical issues.

For instance, they confirmed the health risks associated with tobacco, the environmental harm caused by acid rain, and the impending threat of global warming.

What is particularly intriguing is that those challenging this scientific consensus were not typically scientists within those respective fields. The four key people we studied - the four original "merchants of doubt", were Cold War physicists, but had little or no expertise in climate science, atmospheric chemistry, or anything to do with public health. In short, they were outside the relevant expert scientific communities. And their motivations were ideological, not scientific, which led them to align initially with the tobacco industry, later with libertarian groups advocating against government intervention in the market. These individuals framed government interventions as encroachments on personal freedom, effectively stoking fears of sliding into totalitarianism - a theme we delve into further in our latest book "The Big Myth."

Our research in "Merchants of Doubt" primarily focuses on two key aspects: the mechanisms employed to cast doubt on science and the motivations driving these actions. Essentially, our book explores the "how" by illustrating various means, both legitimate and illegitimate, used to sow doubt. Often, these "merchants" exploited science's inherent uncertainties, even though science thrives on acknowledging and addressing uncertainty. They took an aspect of science that should be a strength - its transparency in identifying areas for further investigation - and twisted it into a weakness, suggesting that if we don't know everything, we know nothing. This strategy is insidious because it exploits a kernel of truth to erode public trust in science.

Other tactics employed were far less honest, such as presenting established scientific facts as unknown - like attributing climate change to volcanic activity or suggesting that cloud feedback would halt global warming - claims that were repeatedly debunked.

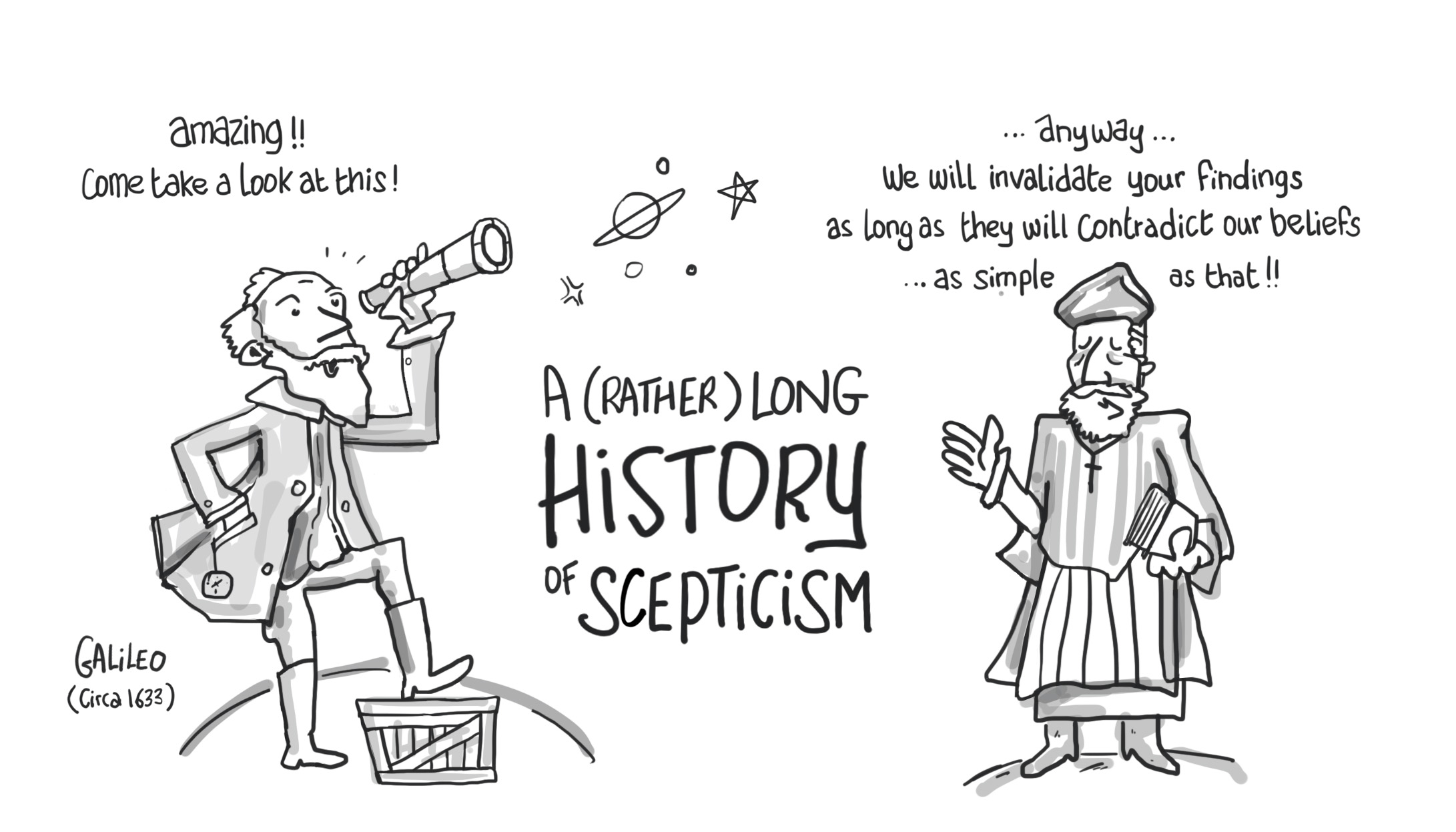

Historically, how would you describe the trend towards questioning established scientific findings?

Scepticism towards scientific discoveries is not a new phenomenon and has a long history. It often arises when scientific knowledge challenges deeply entrenched political, religious, or personal beliefs. Historical instances like Galileo's clash with the Catholic Church, resistance to evolutionary theory, or the persecution of geneticists in Soviet Russia exemplify this pattern.

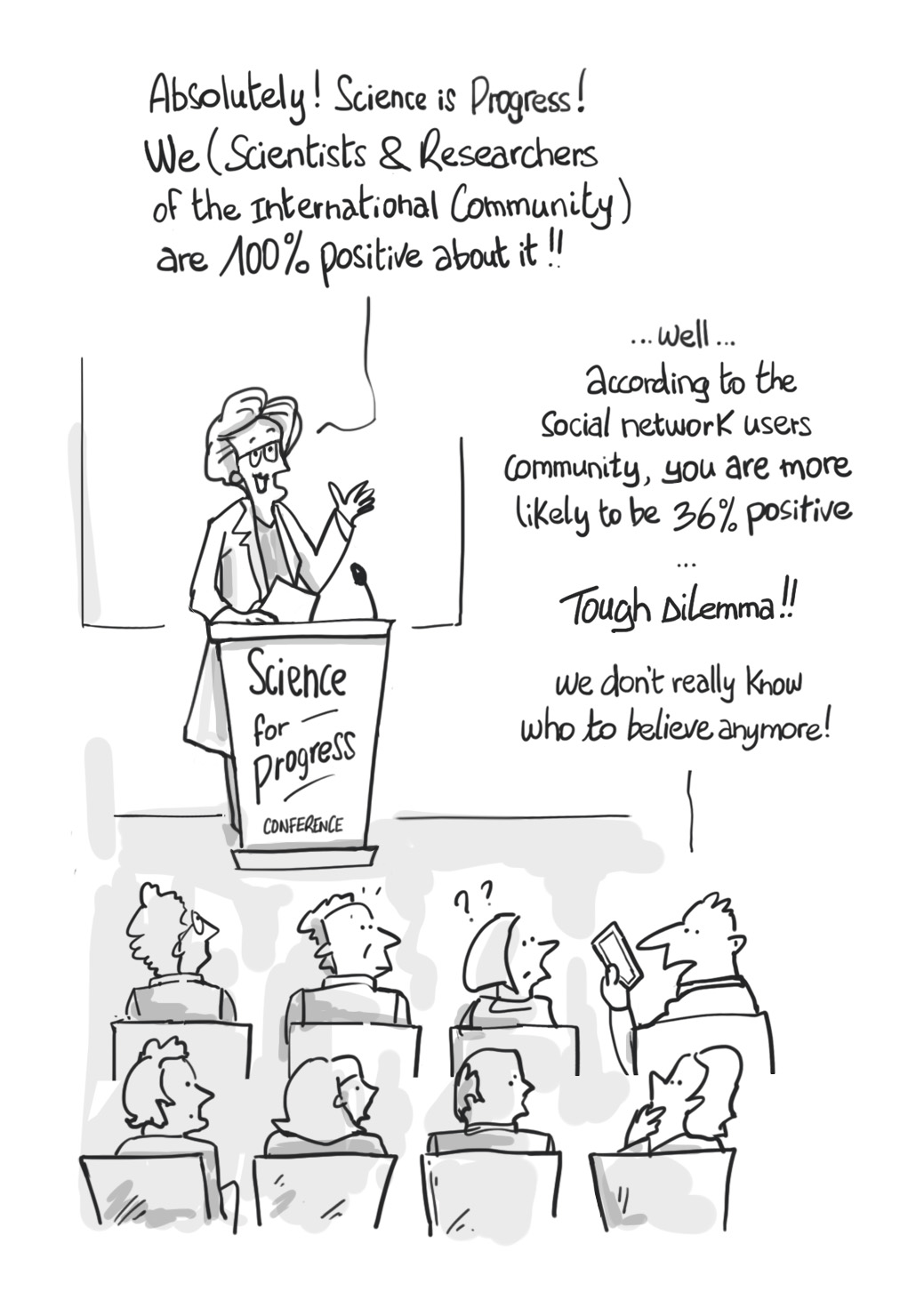

What distinguishes today's scepticism is the context in which it unfolds. In current democratic societies, scientists increasingly face harassment and scepticism, often politically motivated, and sometimes well-funded by groups external to the scientific enterprise. Social media amplifies the rapid spread of opinions, sometimes lacking nuance and accuracy, further complicating matters. For scientists, especially those of my generation and older, being cast as adversaries is a jarring experience.

This is particularly striking because democratic societies have historically supported science. Throughout the 20th century, American and European governments, along with foundations, provided substantial backing for scientific endeavors, fostering prestige and support within the scientific community. Hence, encountering harassment and scepticism in democratic societies is unsettling, as it runs counter to the historical alignment between science and democracy, at least in the last century or two. Sociologist Robert Merton argued that science and democracy naturally align due to their shared values of open inquiry, the free exchange of ideas, and a willingness to question and criticise. That may have been an oversimplification, but there was something to it. In any case, many scientists grew up believing it was so. The current wave of antagonism towards science in democratic societies therefore feels different and profoundly shocking to many scientists. Personal experiences, such as receiving threats, provide a deeper understanding of the challenges scientists face today.

You mention the role of social networks in amplifying doubts about science. How would you characterise this?

Social media didn't create the challenges we face with science harassment and disinformation; these have been around as long as humans have communicated. However, social media has intensified these problems in several ways.

The most obvious impact is the rapid spread of disinformation. As we talk, industries like the gas sector are flooding social media with climate change denial. Social media makes it quicker and cheaper to spread disinformation widely. Disinformation often spreads faster than the truth because sensational claims grab attention. The "merchants of doubt" don't need to prove that climate change isn't happening; they just need to sow enough doubt to discourage action. This strategy appears simpler, as it creates confusion rather than substantiating a point. It is remarkably easy to confuse people, a phenomenon amplified by the internet and social media.

Another critical aspect is the behavior of social media companies themselves, which, in my view, have been grossly irresponsible. They are aware of these issues and have set up task forces, but their efforts have clearly been insufficient. Some platforms seem to show a deliberate disregard for the consequences of their actions. For instance, during the COVID pandemic, the Center for Countering Digital Hate found that a substantial portion of vaccine disinformation could be traced back to a dozen individuals or organisations. Solving this problem should be relatively straightforward, but in most cases, social media platforms have refused to act decisively, likely due to financial interests.

How would you define truth in today's context?

Good question! If I had the answer, I would write that book and then I would retire because, you know, it is a question as profound as those posed by Aristotle and the Bible. Obviously, we are not going to solve that problem here today. Truth, in a pragmatic sense that most scientists employ, is the pursuit of understanding the natural world as it truly exists, not as we wish it to be. Science revolves around collecting evidence, testing theories, and building hypotheses that align with this evidence and our observations of the world.

One way to test the accuracy of our scientific knowledge is whether it empowers us to achieve tangible results in the world. Drawing from American pragmatist philosophers like Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, we test truth in real-life situations.

If our scientific knowledge enables us to develop an effective vaccine, it suggests that our understanding has grasped an aspect of the natural world that is sufficiently accurate to yield practical outcomes. but it is operate effectively. This aligns with William James's idea of testing truth in the making, validating it through real-world actions. My views are more or less aligned with that idea. If I were to deny gravity and jump from a fifth-floor window, the consequences would likely confirm the truth about gravity, regardless of my beliefs, and even though we can argue about whether what I really experienced was gravity or the bending of space-time.

How can agnotology help climate action?

When people recognise they have fallen victim to disinformation, it often ignites a powerful emotional response - anger. This anger can serve as a potent motivator for change.

When individuals believe there is just a lot of confusion surrounding critical issues, it can be disempowering. They might think, "I'll wait until they figure it out" and continue with their current habits, like consuming hamburgers or driving gasoline-powered cars. However, when you can unveil the deliberate nature of disinformation and its source in vested interests seeking to preserve their political and economic dominance, it becomes profoundly empowering.I have seen the impact of this revelation. People attending my talks sometimes audibly gasp when they realise the extent of the manipulation. It is an exciting moment when you can visibly witness people's understanding and motivation shift.

In your latest book “The Big Myth”, you argue that the promotion of the free-market ideology has hindered sensible policies addressing climate change or social issues. Is this a “myth” that societies based on the American model can escape?

Over the last four decades, a prevailing ideology has favoured the deregulation of markets and the reduction of protections for workers, consumers, and the environment. Although this has led to a certain amount of prosperity, it has prevented a proper accounting of the real costs of economic activities, such as climate change.

The challenge lies in dealing with these "external costs." For example, when I buy gasoline, I pay for production and profits but not for the climate damage caused by burning it. These costs are now in the trillions annually, recognised by institutions like the International Monetary Fund.

The solution is well-known among economists: internalise external costs with tools like a carbon tax, requiring governmentintervention because only governments can collect taxes. This highlights the core issue - the prevailing ideology emphasising individual responsibility and freedom has led to the belief that we can individually solve these complex problems. Yet, in the case of climate change, only governments can implement some of the key solutions.

In Europe, you will find a greater willingness to engage in this conversation. However, in the United States, things get trickier, mainly due to the entrenched anti-government ideology on the right.

How does disinformation impact the functioning of democracy and hinder progress ?

In a democracy, having good information is paramount. It is the bedrock on which we make choices. Imagine thinking climate change is a hoax; you wouldn't support a carbon tax, now would you? That is why disinformation is so devastating. It clouds people's judgment, and those who spread it know what they are doing. Remember the tobacco industry? They knew their product was deadly, but they concocted a web of deceit, casting doubt on the science. They were mongering. Now, think about how that affected people's decisions. If folks thought smoking was not so bad, they would keep lighting up, and the industry knew that.

Disinformation doesn't stop at individuals; it can warp entire societies. It corrodes the foundations of democracy. When people don't have good that is exactly why it is done. Democracy relies on an informed electorate. Disinformation undermines that fundamental principle.

So my friend, we need to keep a vigilent eye on the disinformation game, especially in critical matters like climate change. It is not a matter of misinformation; it is about the calculated deception that harms our democracy and hinders progress.

How do you envision tomorrow’s role of science in society?

The role of science in society tomorrow, that is quite the puzzle. You see, I have argued this before, and I will say it again, we need not just natural science but also social science. Many of these complex problems we are grappling with, scientists - and when I say scientists, I mean those in the natural sciences - often mishandle them. They lack an understanding of the social dimensions, the cultural and political forces at play. Over my lifetime, I have seen scientists facing resistance to their work and thinking, "Well, it's just misinformation. We'll provide clearer information,and all will be well." But when you are up against disinformation, more facts won't cut it. You've got to step back and examine the broader cultural landscape.

This is precisely why I'm a historian. Historical legacies endure, shaping the way we think, even if they happened centuries ago. They influence personal and communal identities, as well as national identities. historical

narratives and identities. Italians, French, Germans - they all have their distinct national identities.

Natural scientists often overlook these factors because they are not trained to consider them as causal elements. That is why we need a encompassing concept of science, akin to the German notion of Wissenschaft, where knowledge production encompasses cultural knowledge. Historians are part of German academies, while in the United States, when we talk about science, we mostly refer to the physical and natural sciences. a more Wissenschaft-lichte notion of science. It would be a step toward comprehending how natural scientific knowledge can effectively interact with the intricate social and political realities we face.

Naomi Oreskes

Renowned biologist and historian of science, Naomi Oreskes is the author of the bestseller “Merchants of Doubts” (2010). Her research on the role of science in society and the role of disinformation in blocking climate action, is highly recognised. Her latest book "The Big Myth" published in 2023, takes us into the mysteries of the production of doubt and ignorance.