Behaviours that do not follow our logic

Zoom on 12 cognitive biases

Facts are stubborn. They remind us of our planet's ever more critical state, warnings of the growing dangers awaiting. They urge us to act as quickly as possible. Faced with this injunction of an implacable logic, our behaviours, however, remain too often unchanged. Why ? Neuroscience provides part of the answer by analysing the many cognitive biases that are at work in our information processing.

Our tendency to adopt irrational behaviours was brought to light by psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in the 70's. While studying our individual economic decisions, they introduced the notion of cognitive biases. Their finding: our rational and logical thinking can be hampered by “deviations” in the cognitive processing of information. Our brain cannot process all the information. These shortcuts, generally unconscious, are necessary. Still, they are very often sources of errors in judgment.

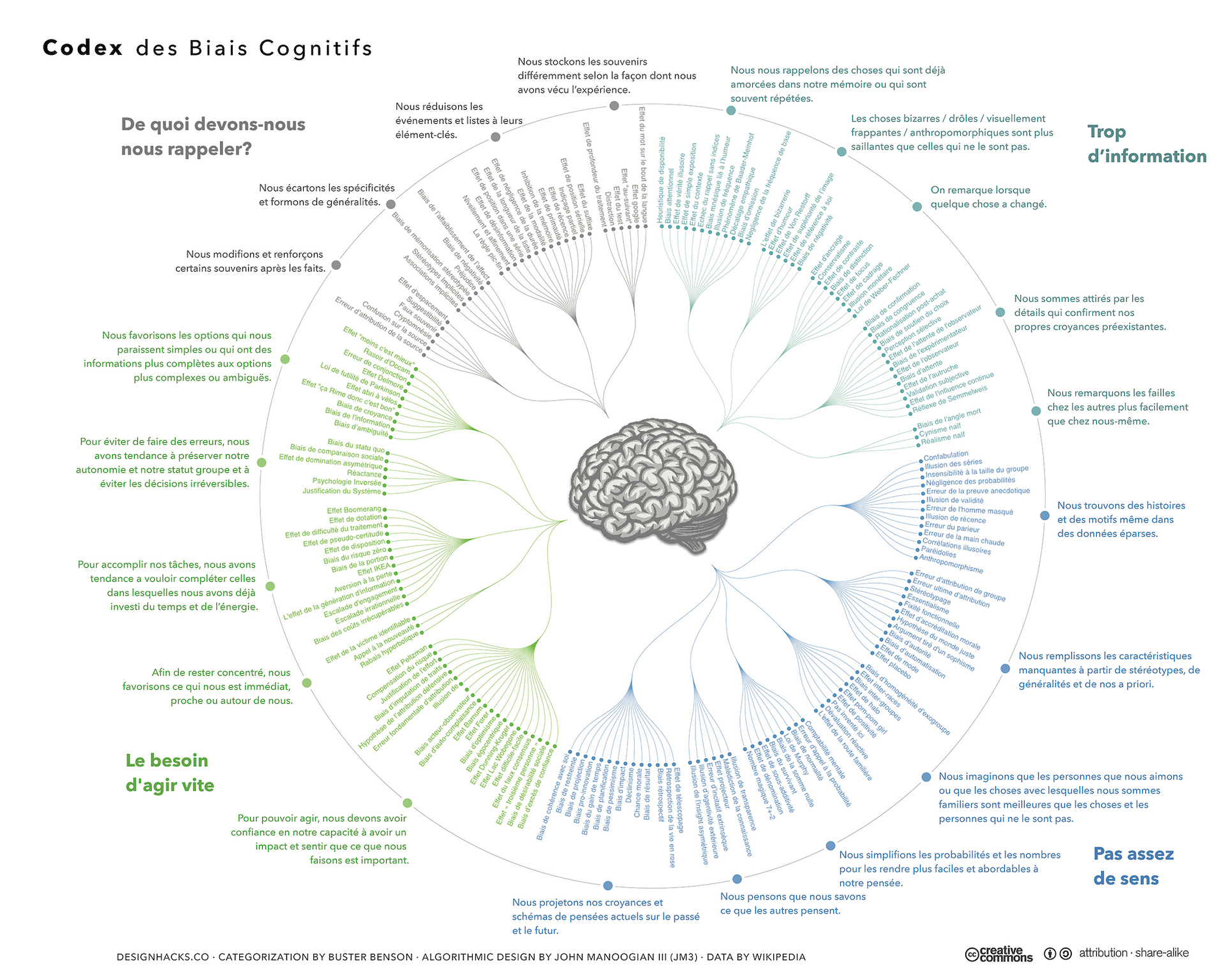

Since then, research on these mechanisms has multiplied, giving rise to the identification of a wide range of biases (see Cognitive biases codex page 58). Some of them particularly hinder us in our move to action when it comes to preserving the environment. Let’s have a look at them.

1. The Present Bias

We tend to favour the present moment. This happens to the detriment of a projection into the distant future. In other words, short term wins over long term. This explains our tendency to procrastinate, and our difficulties in changing habits. This represents a major obstacle in terms of climate change where you have to know how to project yourself beyond your daily life, onto more distant horizons... even if they are getting dangerously close!

2. The Optimism Bias

It is a surprising belief: everyone assumes that they are generally less at risk than others. This blissful optimism certainly does not help us in our perception of the dangers associated with changes in our environment.

3. The Normalcy bias

Events will unfold in the future as they have conventionally happened in the past. This very reassuring hum of normality leads us to underestimate the possible occurrence of catastrophes.

4. The Status Quo Bias

Leave the situation as it is, lest the alternative cause problems. This aversion to change unfortunately keeps us in very risky positions. Faced with the urgency of the environmental situation, this bias slows down our ability to respond effectively. It pushes us to maintain the operating system in place.

5. The Conformity Bias

This tendency to think and act as others do hampers our ability to drive and effect change on many issues. Conversely, this bias will become an ally of the environmental cause when the majority of individuals have integrated action in favour of our planet into their behaviour.

6. The Confirmation Bias

We often only recall information that supports what we think. This trend, identified through numerous studies, encourages us to value the messages and transmitters that go in our direction. This phenomenon explains the persistence of climate change denial despite the accumulating scientific evidence. It is particularly present in the context of social networks and leads to the polarisation of opinions.

8. The Techno-solutionism

The prevalence of this bias is significant: it is the idea that all problems will find a solution thanks to current or future technologies. A belief that shifts the responsibility onto science and research and exempts the average citizen from acting in their own way.

9. The Cognitive dissonance

Our brain sometimes plays tricks on us by refusing to see certain realities to avoid questioning our firmly established beliefs or practices. Taking into account contradictory information would otherwise create dissonance, which is challenging to deal with.

10. The Bystander Effect or Dilution of Responsibility

The analysis of the murder of Kitty Genovese, killed in front of numerous witnesses who remained unresponsive, made it possible to identify this very surprising bias. It designates a phenomenon of inhibition of the helping behaviour in an emergency situation when other witnesses are present. This is known as dilution of responsibility because the individual will try to evaluate the response of the other person before acting, which will at least postpone or even block his/her intervention. This wait-and-see attitude is a strong explanatory factor for the lack of change in environmental protection behaviour.

11. The Learned Helplessness Bias

We have sometimes felt that our actions in favour of the environment had an extremely limited impact given the magnitude of the issue, and that the situation continued to worsen despite our change in behaviour. Icebergs continue to melt, biodiversity continues to decline, pollution is increasing... This lack of control generates a feeling of 'acquired' or 'learned' helplessness, as well as a resigned and defeatist attitude. It tends to recur even in subsequent situations where the individual's behaviour has a strong impact.

12. The Commitment Bias

Once engaged in one direction, the individual has difficulty changing gears. This desire to continue along the path initially chosen, even in the face of increasingly poor results, is a major obstacle to change.

Cognitive biases are broken down into four components here: What should we remember, Too much information, Need to act fast, Not enough meaning.