Our Chains of Vulnerability

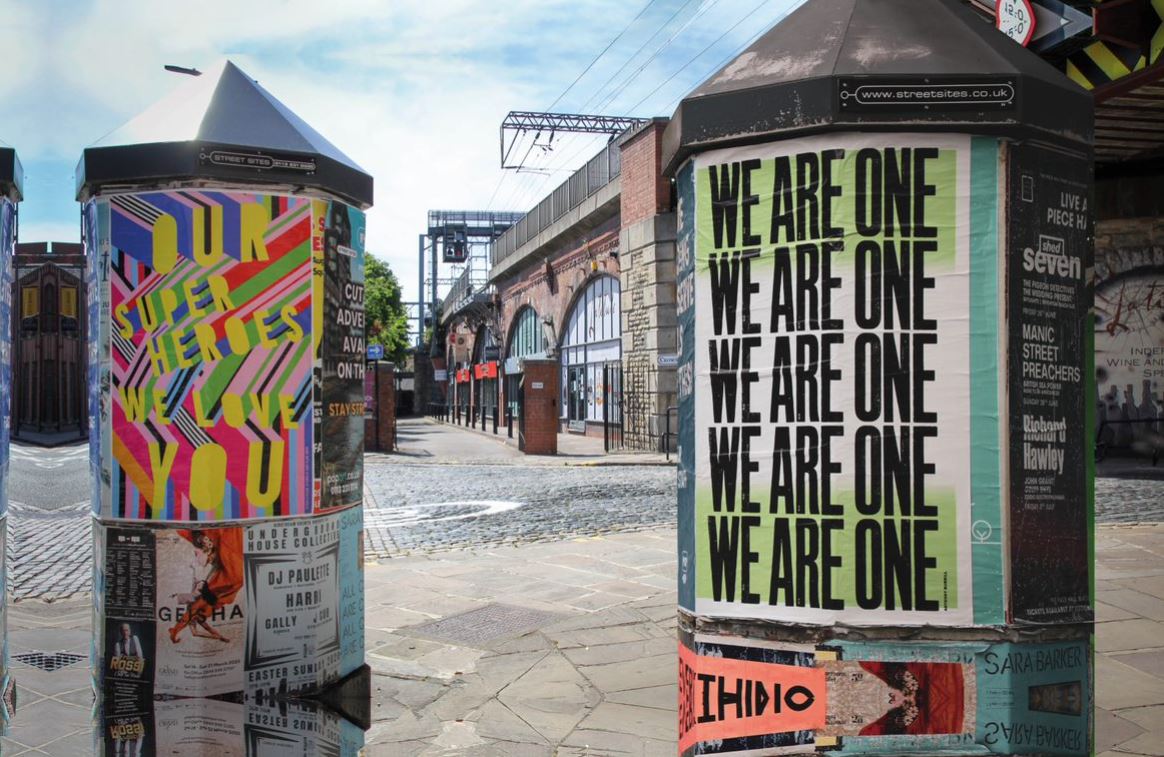

It was to the sound of pots and applause that, at precisely 8 p.m., the confined populations of many of the countries hardest hit by COVID showed their gratitude to the health workers and, more broadly, to front-line workers. This ritual consecrates the more or less lasting heroism of professionals whose social usefulness is nowadays made more vivid, but who, until then, were undervalued in a society that did not know how to express its multiple vulnerabilities. How, beyond this popular demonstration and in a quest for resilience, is it possible to rethink our dependence on others but also, more broadly, on our environment and planet?

Faces for Anonymised Cohorts

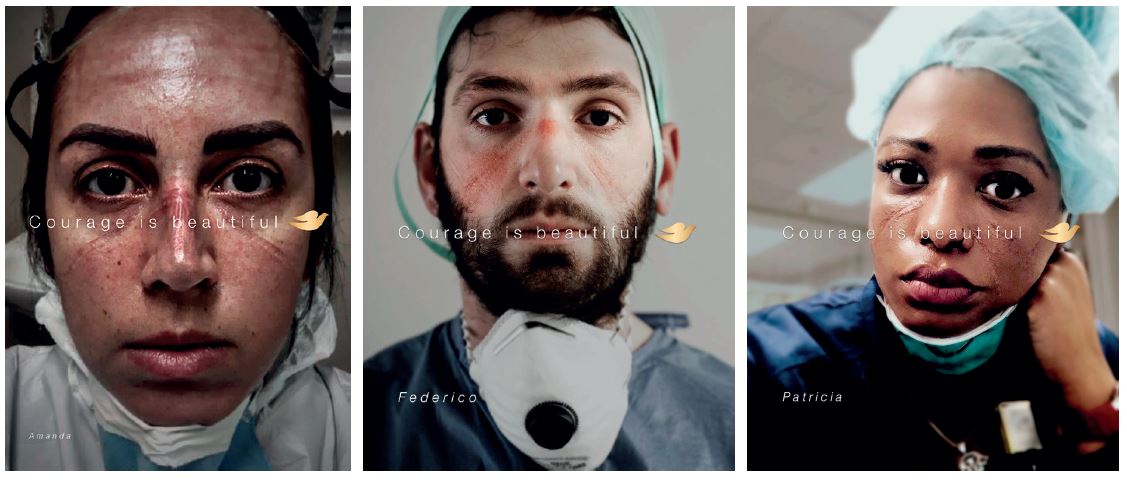

With the health crisis, many artists have sought to bring out of the shadows the women and men who devote themselves, in the banality of everyday life, to saving others or meeting their basic needs. In the United Kingdom, the approach has even been systematised through the hashtag #PortraitsforNHSHeroes, a movement initiated by the artist Tom Croft and which tries to fill an evident lack of recognition for these professions. The observation seems unanimous, and initiatives have multiplied to put faces to vocations. This is also the meaning of Dove's communication campaign. The brand, which has been working for a long time on the question of representations, pays tribute to the nursing staff and invites us to look at beauty through the prism of courage. A new set of values is being honoured, and these faces are designated as the new heroic profiles of our times. This new iconography is a sign. Well, this notorious reversal in representations, so well grasped by Banksy, is it transitory, or does it express a more lasting change, capable of moving the lines, as the artist suggests by naming his work "Game Changer"?

The Dove campaign launched during containment. The brand, which regularly questions our representations, integrates care in its definition of beauty.

Historically Invisible Professions

While the social utility of front-line jobs is today striking, it has so far mainly and systematically been discredited. Apart from a few professions, such as doctors and specialists, for whom very specific skills and advanced scientific and technical knowledge are required, the vast majority of care professions suffer from a chronic lack of recognition in our society. Nursing assistants, life assistants, cleaning agents, the battalions that occupy these functions are generally underpaid and made up of particularly disadvantaged populations. With the pandemic, gestures have been made such as in South Korea, where the government has set up a special voucher policy, or in Italy, where a bonus of 1,000 euros has been granted to care workers for the watch of their children. The crisis has highlighted the precarious conditions of these workers, especially the long commuting distances. Specific initiatives have also come from the private sector to support these populations. For example, the Hilton hotel chain, in partnership with American Express, has made one million overnight stays available to healthcare workers in the United States. These patches remain ephemeral but reflect the striking evidence of precarious conditions in the care sector, and the profound distortion between wages and social utility.

Women as Caregivers

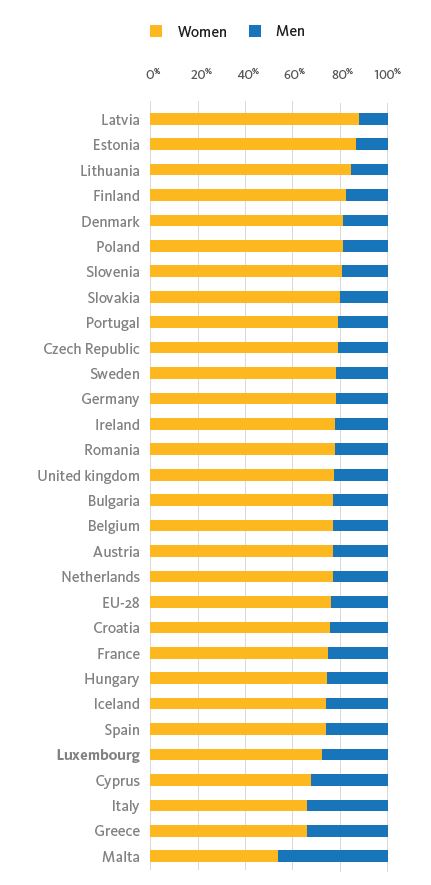

The sociology of caregivers came to light with the COVID crisis. Care, it is evident, is a mainly feminine activity. The figures are striking in this respect: according to the European Institute for Gender Equality, 76% of care workers are women in Europe (and 65% in Luxembourg). They also account for 93% of the staff in maternal assistance and teaching assistance, 86% of the staff in the care and personal assistance services, and 95% of those in cleaning and domestic help. In total, among the 49 million workers in this field in Europe, 76% are women. It is also essential not to underestimate the undeclared share of care provided in the domestic sphere and also outside the family setting. According to the International Labour Organisation, "in normal circumstances, women perform a daily average of 4 hours and 25 minutes of unpaid care work against 1 hour and 23 minutes for men."

This over-representation of women in the field can be explained by our system of representations of a field of care limited to the domestic sphere and traditionally attributed to women. Pascale Molinier, in her book Le travail du care, describes the reasons behind the difficulty of considering care activities as a profession in their own right. She points out that it is traditionally understood that the skills required are not based on particular techniques or knowledge enabling productive work, but rather on an innate aptitude which is naturally present in women.

The feminine nature of these occupations is explained by the porosity between the tasks performed in the domestic setting and those required to practice the professions of care. The care to be provided in the private sphere, for a child or a dependent parent is, in fact, most often carried out by women. But as Fabienne Brugère points out in her book L'éthique du care, "care is not mothering". There is not a feminine nature that assigns it to care and, more broadly, to caring for others. The American specialist Joan Tronto emphasises this point by showing that, even if these qualities are rarely highlighted, men of course "have a disposition for care". The professions of police officers and firefighters are clear examples of this. Caring is, therefore, far from being the preserve of the female gender.

Deepening the Reading Grid

Gender is not the only explanatory variable for understanding who the caregivers are. The entry keys are multiple, and it is interesting to use intersectionality to analyse the subject. Beyond the marker of gender, indications such as social class and origin are also important. According to the recent paper Intersectionality and global health leadership: parity is not enough, co-written by Zahra Zeinali, insists on the need to take these variables into account for the nursing staff. "It is imperative that we look beyond parity and recognise that women are a heterogeneous group… /… We must take into account the ways in which gender intersects with other social identities and how it stratifies to create unique experiences of marginalisation and disadvantage."

The situation is particularly marked in Luxembourg, where, of the approximately 13,000 employees carrying out an "activity for human health", almost 8,000 are not Luxembourg residents, and 5,600 are cross-border commuters. Last may, the Council of the European Union pointed out this specificity as a potential risk for the country. "Luxembourg has one of the most efficient health systems in the EU. Nevertheless, with 49% of doctors and 62% of health workers being non-Luxembourgish professionals, the system is well above the critical threshold of vulnerability", the conclusions of the report indicate.

This trend applies to almost all care occupations, and in many countries, these occupations are often left to immigrant workers. A recent study of the cleaning sector in Luxembourg, conducted by the LISER Institute, confirms this phenomenon by pointing out two particularly prominent markers: gender and nationality. While 83% of employees are women, Portuguese and French nationalities make up 76% of the workforce, with no less than 38% being cross-border workers. Also, precarious family and social situations characterise the profession, which is the combination of activities, short-term contracts and part-time work that are well above the national average. These are, therefore, the keys to intersectionality that allow us to grasp the complexity of the subject.

Vulnerability Trades

One reason why these professions have been systematically made invisible is that they touch on a very sensitive point: namely, our profound vulnerability. Indeed, as Fabienne Brugère perfectly explains in our interview, our societies have been built around the myth of the individual as master of his or her own destiny and in denial of our multiple fragilities and our great interdependence. The current paradigm poses individual responsibility as the only key to happiness, success as the pure result of personal will. And this approach has been self-fulfilling, since the individualisation of society has, unsurprisingly, led to a decline in relationships of social assistance. The net of family solidarity, for example, has clearly been eroded with various phenomenon linked to the individualisation of life courses, such as the geographical break-up of families. This decline in intergenerational care within homes thus implies the outsourcing and commodification of care. Our world is reduced to a sum of individuals in a frenetic quest for happiness. And our society, through advertising or personal development programs, has organised itself to remind us of this. The unit of account is the individual. Edgar Cabanas and Eva Illouz describe the implications of such a phenomenon in their recent book Happycratie. "And it is, they say, jeopardising any construction of collective action."

Our experience with the health crisis reveals our inability to face up to it without strong collective coherence.

Towards an Ethic of Care

This is not the case for the ethic of solicitude, more often referred to as the ethic of care. Indeed, this moral reflection, which has its origins in the Anglo-Saxon world, places interdependence and "caring" at the heart of the approach. It invites us to think about human relationships in relational rather than individualistic terms.

This movement, marked in its beginnings by the analysis of the philosopher Carol Gilligan in her book A Different Voice, invites us to take into account a way of thinking about morality that stems from women's experience of care and which is largely ignored in our societies. It is about hearing the voice of our vulnerabilities and interdependence.

The challenge is enormous because there are many frailties. Our experience of the pandemic has indeed been particularly instructive from a health point of view. But we need to move beyond merely reacting to an imminent danger and move towards an awareness of our systemic vulnerability. The hugs of police officers in response to terrorist threats followed by insults, once the state of emergency is over, are particularly revealing in this regard. What will happen to the applause on the balconies?

It is a question of taking a long-term view because we are facing challenges of unprecedented magnitude. From an ecological point of view, one extreme event follows another to sound the alarm. The well-established observation of our transition to the Anthropocene era is precisely that which poses human action as a determining factor on the environment on which we depend. Our interdependence is glaring, and it is urgent to think here of a non-utopian care society that takes care of our world and us living together. Faced with the obsolescence of many of today's professions and the galloping automation of our means of production, it is indeed conceivable, as Jeremy Rifkin points out, that, in the context of a forthcoming industrial revolution based on clean energies and means of communication, tomorrow's professions will mainly become human and care-oriented with added value. Jobs of great social utility located precisely where the machine cannot replace humans.

Our experience with the health crisis reveals our inability to face it up without strong collective coherence. We must take this opportunity to build our resilience together, by making our interdependence the "foundation stone of our social pact", as Emmanuelle Duez strives to say, calling for a collective approach to resilience, whether at the level of society or the company. It is a question of really making society, of adhering to a project where attention to others is prevalent, where interdependence and universal responsibility are called for. This is reminiscent of the wisdom of Southern African Bantu Ubuntu, a notion that was invoked during post-apartheid national reconciliation and by Nobel Peace Prize winner Desmond Tutu in his book Reconciliation: The Ubuntu Theology: "Someone who is Ubuntu is open and available to others" because he is aware that he "belongs to something bigger".

To be read also in the dossier "Towards a Society of 'Care'?":