Tattoos: Clichés are Hard to Break

On the shoulder, on the arm or on the ankle... tattoos are a must in the streets! But what is its status in the workplace? Globally appreciated in creative environments, it is not certain that it will be perceived with as much enthusiasm in a meeting of a more conventional company. This is what a recent study by IMS Luxembourg questioned: are unconscious biases persisting towards ink carriers?

A recent craze, a thousand-year-old practice

Tattooing has been present in the world since the Neolithic period, as witnessed by mummified skins and archaeological records. The oldest trace of tattooing was found on the body of Ötzi, the Iceman, dating from about 3300 BC. When he was discovered, he had no less than 61 marks all over his body. Other tattooed mummies have been found in Greenland, Mongolia, Eastern China, but also in Egypt, the Philippines, or the Andes. On the other hand, this practice was lost in the Middle Ages, probably because Christianity, then all-powerful in European society, explicitly forbade body markings.

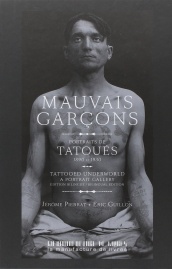

If it was until recently reserved in our latitudes to a minority of people, signaling their belonging to certain social groups such as the LGBTI community, the hippie movement, or men in certain professions deemed "virile" (sailors, for example), interest towards tattoos has gradually widened within our societies since the 1970s. In 2018, the Dalia polling institute revealed that more than 40% of the population was concerned within the 17 countries studied. In the survey conducted last March by IMS Luxembourg to assess tattoo perceptions in the professional world in the Grand Duchy, 39% of respondents said they had at least one tattoo. The figures are clear: tattoos are now popular! And today, Italy, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and Germany are at the top of the list of tattoo-friendly countries. However, if it is no longer associated with marginalised communities in most Western societies, its democratisation remains affected by perception and representation disparities.

Prejudices that stick to the skin

The tattoo associated with lack of education, reliability, or rebellion? Or, on the contrary, associated with self- confidence or creativity? If these stereotypes seem outdated, they are still at work, especially in the corporate world. The literature on the subject is far from exhaustive. Still, Andrew Timming, professor of human resources management at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology, has studied the issue. In particular, he explored in an article "What Do You Think of My Ink? Assessing the Effects of Body Art on Employment Chances" (Wiley, 2017) the influence of tattoos on the assessment of applicants' employability in companies. In particular, his study drew on existing literature on the social psychologies of stigma and prejudice. He studied the various reactions when candidates were presented with simple photos. The conclusions indicate that tattooed and pierced candidates are more often perceived in a pejorative way by potential employers than candidates without the same characteristics.

In the Grand Duchy, the survey results conducted by IMS Luxembourg show that both employers and employees believe in the existence of many stereotypes against ink holders. For example, 57% of employers think that tattooed people can be considered rebellious. Other clichés also seem to persist, such as the idea that tattooed people come from more disadvantaged backgrounds. Moreover, many employees (9%) and employers (15%) believe that this stereotype is still true today. On the other hand, the actual discrimination in employment seems to be weak. This is what Timming observes in his work, a finding that appears to be confirmed by the results of the IMS Luxembourg survey: these show that more than 83% of tattooed people have never experienced any discrimination in their professional sector. The remaining 17% of the tattooed people said they felt a change of perception from their colleagues or superiors but no direct discrimination. How can we explain this apparent gap between the significant existence of stereotypes and the real discrimination against candidates and employees?

Front line jobs particularly concerned

It is difficult to afford to show your tattoo in certain professions. This is what a large majority of employees (70%) and employers (76%) consider as one of the most widespread stereotypes. And they are not far from a certain reality! A more recent analysis by Professor Timming found that discrimination is more prevalent when close customer contact is involved. The more candidates apply for a customer-facing position, the lower their chances of being selected. The reasons given are not related to skills but to promoting a specific image of the company. It would be the jobs of customer interface, particularly visible, where the organisation's representation is strong, which would be the most affected by discrimination in employment because of tattoos. These conclusions provide a general understanding but should be taken with caution. The sector or the company's profile will obviously play a role, sometimes even the opposite. Companies looking for a younger or more non-conformist clientele, for example, will tend to value these body inscriptions, thinking that they can deduce qualities in the candidate.

Generally speaking, there are negative or positive associations between tattooing and some professional sectors or jobs. It is then our unconscious biases that impact our perception. But what seems to be particularly at work here (in cases where tattooing is avoided in close contact with customers or more widely in representative professions) is the anticipation of stereotypes, known or not, in others. What we imagine others will think. These are the meta-stereotypes. These meta-stereotypes can have such a powerful effect on our thinking that they have a distorting effect on our ability to perceive the social world with clarity. For example, nearly three out of ten tattooed people say they are embarrassed to show their tattoos in some professional situations. A figure that rises to two-thirds among non-tattooed people (who would be embarrassed to show it if they wore one). These people anticipate the gaze of others, and sometimes in the wrong way, which creates situations of self-censorship. The same is true for some recruiters who might sometimes wrongly assume a certain embarrassment in their clients and not select a tattooed candidate.

Intimate representations in the corporate context

More fundamentally, the tattoo, embodiment of messages with multiple contents, raises the border between the intimate and the professional world. Indeed, it is a flood of inscriptions and symbols of an eminently personal nature bursting into the corporate sphere. The individual presents himself in new ways.

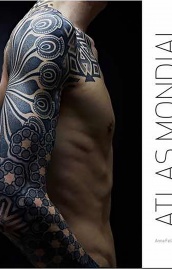

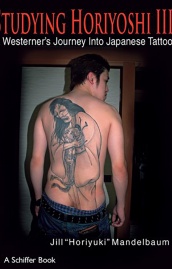

If taditionally, many societies around the world use and inscribe the tattoo at the heart of a collective process as a marker of belonging to a group, the tattoo fever that has been observed more recently in Western societies, is a sign of a very personal expression based on the individual's singularity. A souvenir of a trip, of a loved one, a first job, a diploma... These ink marks express personal values or represent family or love ties, or sometimes symbolise a change in life.

|

|

It is difficult to reduce them to a simple beautification process. According to social scientist David Le Breton, this "private and public object" is a "common element of self- construction in a world where it is important to attract the eye with a socially significant feature". These words underline the importance of individual affirmation that lies in this modification of one's appearance. It contributes daily to shaping the identity of its wearer, notably through the eyes of others.

The tattooed decide to share, to reveal or not this part of their identity. Many ink wearers choose to place their tattoos on concealable areas to play with the multiple identities that characterise us all and leave the intimate outside the professional sphere. Often they adjust to circumstances, whether in the family or professional environment, and adapt to what is expected of them, or at least what they imagine to be the constraints of their social environment. These people will not give voice to any part of their self-expression to 'fit in' with the social framework they want to maximise their chances of fitting in. Yes, body marking, when it is visible, often exposes intimate aspects to the professional world. It can then be perceived in the eyes of others as an open door on the private life of an individual. What limits should be imposed or self- imposed? Everything depends, of course, on the context and the message carried by the tattoo. Most employers who can tolerate a tiger's head or butterflies would probably be less inclined to accept imagery with political, religious, or inflammatory symbols. More than the medium - which is now more commonly accepted - it is the message that is at stake.

However, both for these borderline cases of problematic personal expression and facilitating the logical acceptance of the majority of tattoos, very few companies establish a policy and address the issue in their internal regulations. This is notably the case in Luxembourg, where 89% of respondents to the IMS survey said they made no mention of it. Thus, the subject is largely ignored even though it is, above all, to formalise a question of mutual respect which is essential to living together in the workplace.

To be read also in the dossier "Ink carriers in the workplace":