Planetary Emergency: Aiming for Climate Neutrality

420 ppm. This is the record level of carbon dioxide (CO2) currently measured in the atmosphere by the World Meteorological Organisation. It represents 3.276 trillion tonnes of CO2. This level, unseen for three to five million years, corresponds to a time when global temperatures were 2 to 3°C higher than today and sea levels stood 10 to 20 metres above their current height. As temperatures continue to rise and the effects of climate change grow increasingly severe, the need to reach climate neutrality has become more urgent than ever.

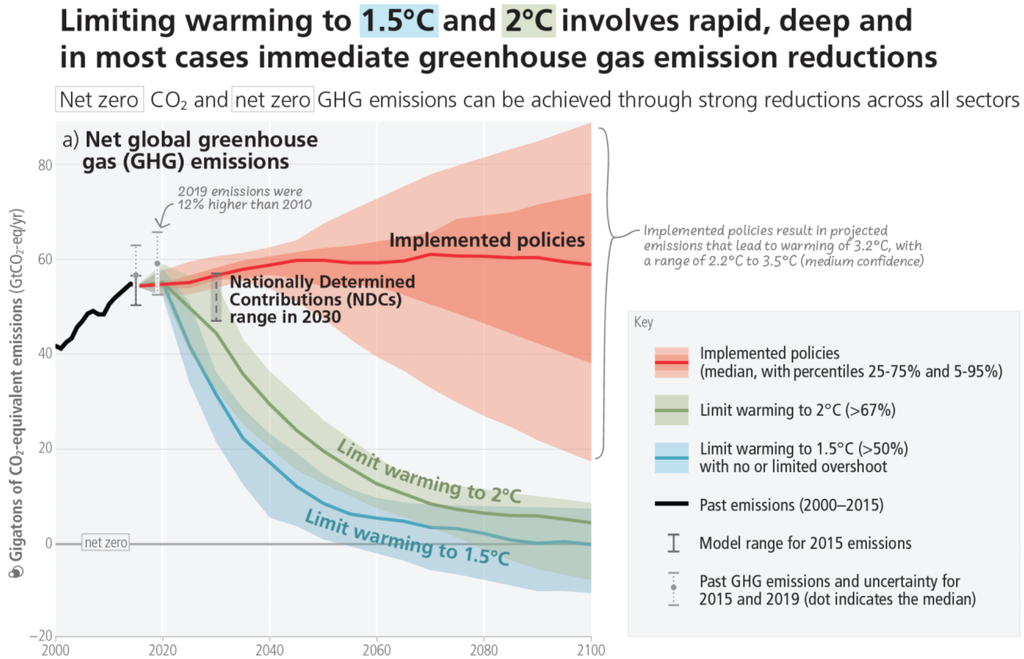

Limiting global warming requires nothing less than a profound transformation of our energy, industrial and economic systems. This is why climate neutrality has become a central goal in climate policy worldwide. Included in Article 4.1 of the Paris Agreement, it refers to achieving a balance between human-generated emissions and the amount of greenhouse gases absorbed by carbon sinks during the second half of this century.

In practical terms, reducing emissions is not enough. We must also remove CO2 from the atmosphere to offset the residual emissions that cannot be avoided. This approach has become all the more essential now that the 1.5°C threshold was breached in 2024, reinforcing the need to minimise the risks linked to a warming trajectory that is already underway.

This 1.5°C threshold is a physical boundary, clearly defined by the international scientific community and supported by hundreds of studies compiled by the IPCC. Climate scientist Johan Rockström particularly emphasises this point. According to him, surpassing this limit triggers global tipping points, placing billions of people at risk of irreversible upheaval. Based on early 2025 estimates (Friedlingstein et al., 2024), the remaining global carbon budget — that is, the amount of CO2 humanity can still emit, to retain a one-in-two chance of bending the trajectory to stay below 1.5°C — is between 160 and 310 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent. If we aim for a reasonable probability of success, this budget drops to around 150 gigatonnes, which is roughly equivalent to four years of current global emissions. At this pace, we must either reduce emissions by 15 percent each year or remove massive amounts of carbon from the atmosphere to achieve climate neutrality.

As Johan Rockström puts it, "whether we like it or not, we have already used up a major share of the remaining carbon budget…/… We no longer have a choice: we must scale up carbon removal dramatically, transform agriculture into a net carbon sink and accelerate the phase-out of fossil fuels."

Limiting warming to 1,5 and 2°C involves rapid, deep and in most cases immediate greenhouse gas emission reductions.

These carbon removal techniques are referred to as CDR, short for Carbon Dioxide Removal. They are also known as negative emissions solutions. According to IPCC projections, achieving the target would require the removal of between 5 and 16 billion tonnes of CO₂ per year by 2050. However, in 2023, the global removal rate was only around 2 billion tonnes per year (Smith et al., 2023).

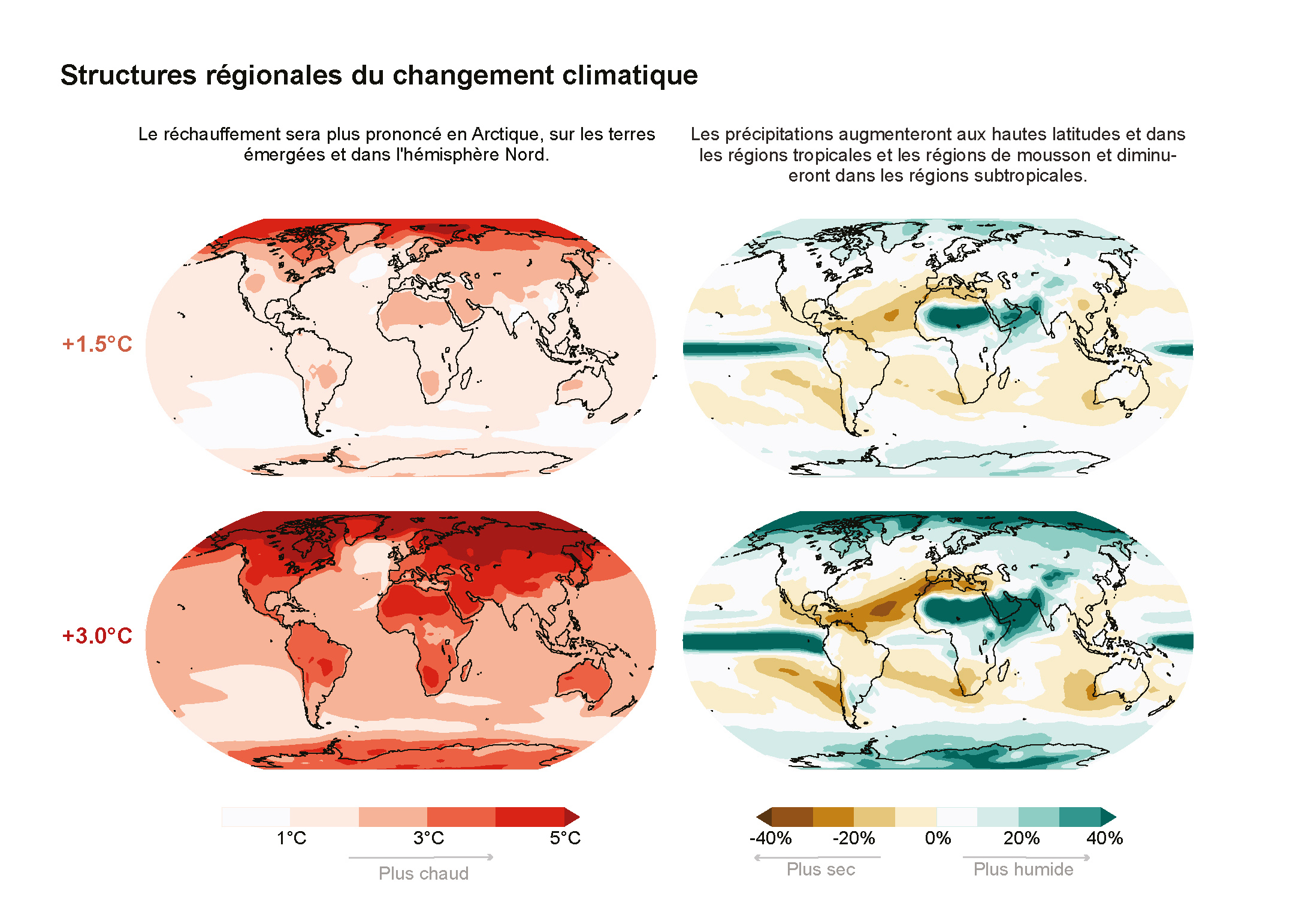

Climate change is not uniform, and its regional characteristics intensify in relation to the level of global warming.

It is essential to stress that these technologies must never be used as an excuse to delay or avoid cutting emissions at the source. As underlined by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development, we must not rely solely on carbon removal solutions. Doing so would risk slowing down efforts to decarbonise value chains and would place excessive pressure on natural ecosystems and resources.

The scientific consensus is clear: climate neutrality will only be achieved through a combined and rigorous approach that includes both substantial emission reductions and effective carbon removals.