Possible Future Scenarios

A science-based approach

Over last century, we observe an increase in mean temperatures and in sea levels. Over 1880-2012, the mean surface temperature has increased by 0.85°C. To understand this evolution and the underlined dynamics of the atmosphere, the oceans, the biosphere and the poles, models of the Earth system have been developed. These have been validated by reproducing past evolutions.

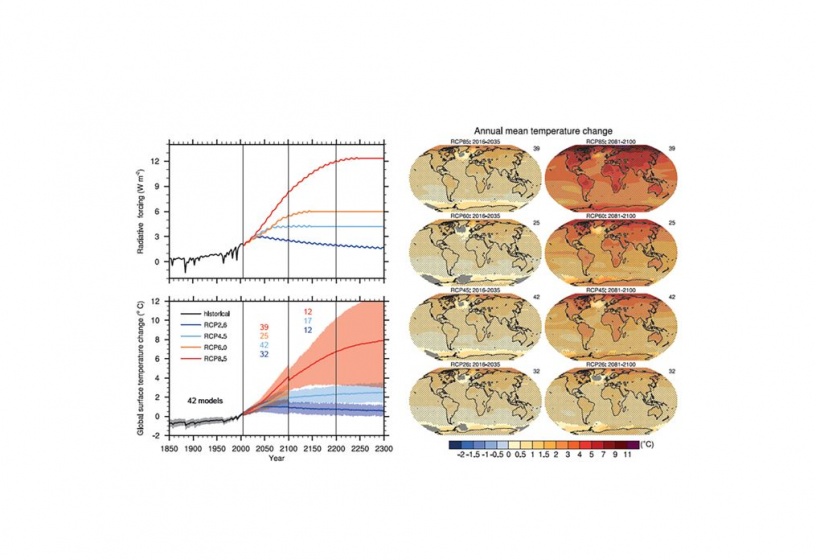

The need for clear results has fostered the dialogue between communities. Scenarios representating different futures have been developed, like the Representative Concentration Pathways (RCPs). For the optimistic “RCP2.6”, models show a global warming of 1.0°C by 2100, with reference to the mean of 1986-2005. But for the pessimistic “RCP8.5”, the global warming is here of 3.7°C by 2100. Nevertheless, these mere number hide risks. Locally, warmings may be much warmer, in high latitude for instance. Besides, these numbers are annual trends. Seasonal and daily variations are also modified. The temperatures we are use to will be shifted, non-homogeneously, with much higher temperature peaks.

Surging seas mapping

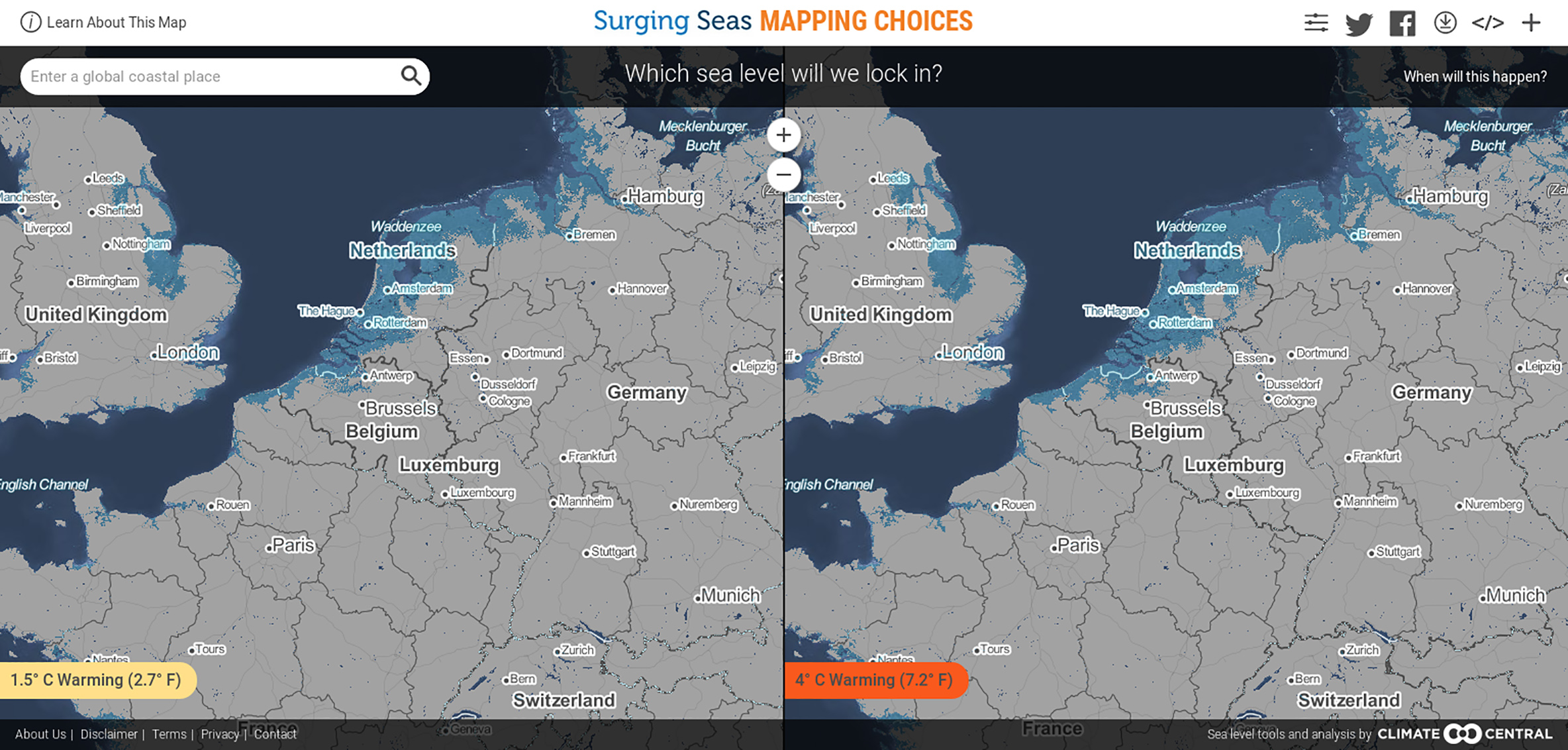

Some regions will then see their rainfalls diminish, which may create or stimulate existing geopolitical tensions about access to water. Other regions will see their floods worsen, causing the associated costs to increase. Events such as heat waves or hurricanes are expected to become more frequent and more intense. Fisheries and agriculture would have their burden, with a decrease of the global food production. As for the biodiversity, entire ecosystems are endangered. One must also deal with unequal sea level rise within different regions. Entire islands are at risk to be submerged, forcing their population to become climate migrants. This elevation threatens whole territories, including key cities built on shores.

To combat climate change, the Paris Agreement aims at keeping global warming below 2°C, or even 1.5°C, by 2100 above preindustrial period. Even though this target will not be easy to achieve, we must not fail. The Earth keep changing after 2100, and it is very likely that not all climate changes are totally reversible

Christophe Cassen

Research Manager at CIRED in the field of the technicoeconomic modeling and in charge of the scientific collaboration with SMASH.

Yann Quilcaille

finishes his PhD thesis in climate sciences at CIRED and LSCE. He analyzes the climate consequences of transformation pathways.