Sailing for Zero-Emission

Meet Jean Zanuttini, President of Neoline Project

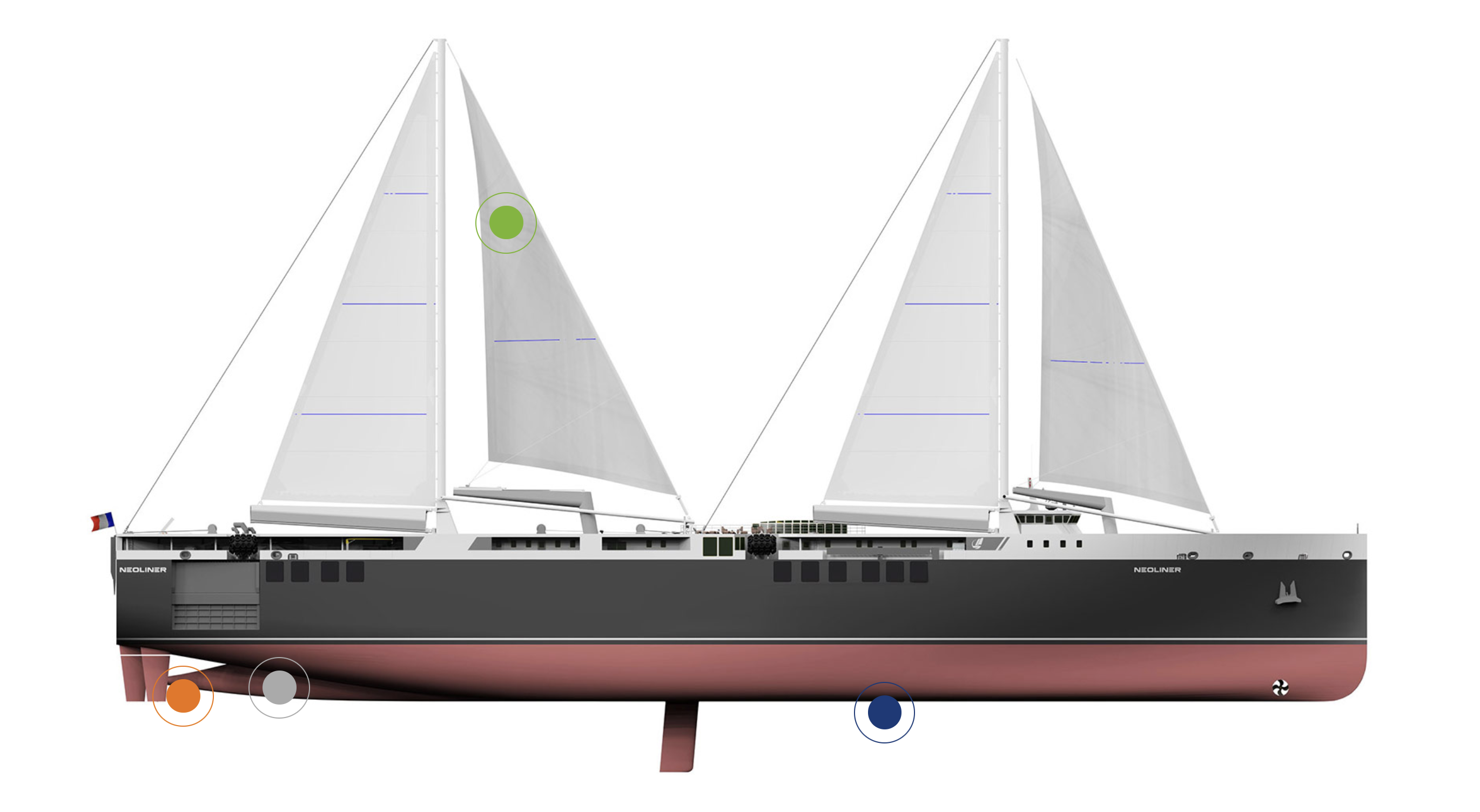

4,200 square metres of sail area, 136 metres in length, an innovative weather and routing system - this is what the cargo ship of tomorrow, or more precisely, the Neoliner, looks like. In two years' time, this new kind of ship will be sailing between Saint-Nazaire and Baltimore, via Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon and Halifax. Looking for green logistics, many brands have already reserved their seat on board. Jean Zanuttini, who is at the head of the adventure, shares his ambition with us.

INTERVIEW

Sustainability MAG: What is the ambition of the Neoliner?

Jean Zanuttini: The objective is to demonstrate that it is possible to use wind as the main source of propulsion for a ship, while providing an operationally viable transport service. The challenge is to prove that we can, today, with current technologies, make the use of wind on board ships viable. It is really an operational and industrial challenge and, in the background, necessarily a financial one, since it is a profit-making project.

How does the Neoliner differ from other existing sailing ships? What is its main technological innovation?

It is actually a combination of innovations. The first one is that we are using a very large-size, large-capacity rig, with 4200 square metres of sail, which can be folded down to go below decks. This is an important element in order to be able to use commercial sailing ships on all types of routes. We have chosen to opt for larger sail surfaces in relation to the size of the ship, as this is central to the economic model and to reducing impact. Anti-rift systems have also been added under the hull, facilitating windward movement, and are themselves retractable for port entry. Moreover, the energy management on board will allow us to test many modes of operation and we also plan to test hydro generation. The idea here is to generate electricity on board via the propulsion propeller and to recharge the ship’s batteries. This will lay the foundations for an energy mix that can be optimised to try to achieve zero emissions in the long term. We are working to demonstrate the feasibility and relevance of maritime transport that is highly decarbonised. We are not talking about much more than a 10 or 20% reduction.

On your pilot ships, this reduction in emissions is expected to be 80% to 90%?

Absolutely. We estimate that the reduction in emissions is between 80 and 90%, when compared to a service operated by a vessel of similar size, travelling at 15 knots. The reduction in speed plays a major role. By going from 15 to 11 knots, we halve the energy requirement. This is enormous. The rest of this reduction in emissions is of course due to the wind, which we use primarily.

What is the time horizon for achieving this zero emission goal you have set yourself?

We think that we will be able to approach zero emissions about 10 years after the first ship. To achieve this, we intend to increase the capacity of the battery pack threefold. By using slightly newer and higher capacity batteries, we will be able to consider doing the entire port stay with zero emissions in ports where we can plug in at the quayside.

All that remains is to regulate the use of the diesel engine during the maritime phases. It is currently designed to produce electricity on board and, from time to time, to avoid being late if the wind is too weak. On this subject, we are working on ways of recovering energy on board other than wind energy: hydro generation, but also solar energy, wave energy with pitching, etc. The use of a system such as a wind generator is a good idea. The use of a hydrogen or methanol type system could complete the system. We could imagine a fuel cell of modest power but one that would work all the time and allow us to have an energy back-up that would have to come from the ground and be decarbonated in the long term.

So you see, we have already eliminated 80-90% of the needs and we are working on the remaining 10 to 20%.

Will we be able to talk about punctuality or will we have to deal with the vagaries of the weather?

The meteorological revolution allows us to rethink the use of wind on a massive scale. It allows forecasts to be made for a week or even two and can be coupled with systems for simulating optimal trajectories in order to capture a maximum of wind energy while ensuring the punctuality of the ship. In the event of delays, there is always the so-called hybrid fuel propulsion, designed to reach 14 knots. It is in fact this insurance that now allows the crew and the captain to take the risk of using wind power without jeopardising punctuality.

This imperative of punctuality could be questioned at its core. Why should we conform to current logistical standards? Ultimately, can we not imagine a lesser demand from shipper clients in terms of deadlines to be met?

When we started the project, with Michel Péry, who has a complete career in the merchant navy, including 26 years of command, and myself, who sailed as an officer for 7 years, punctuality was the focus of our discussions. We had to be able to say to the shippers: "We will take more time, but we will be punctual". All of them expressed a real tolerance for the duration of transport, especially the maritime transport part. We have never lost a single customer because of a transit time that was announced as being too long. However, they all confirmed that the subject of punctuality was central.

There are undoubtedly routes that are favourable to velic propulsion or certain types of velic propulsion?

As far as geographical areas are concerned, areas away from the Equator and tropical areas are going to be on average more favourable to wind propulsion. The North Atlantic, depending on the season, the North Pacific and the Roaring Forties are interesting areas because the wind is strong and constant. On the other hand, some places are much more difficult, such as the route to Asia (monsoon phenomenon), the Red Sea or the Mediterranean, because there is often too much wind, or none at all. So it is much more relevant to use wind propulsion when there is a good sailing distance between ports. If there is less wind at one moment, it is not a big deal because it will be balanced out on the following days. On the other hand, in coastal sailing with a stopover every day or two, you have to adapt to the weather conditions and the engine must be used. We have seen this with European coastal shipping, we have carried out simulated tests and immediately the share of the vessel's engine is reduced to around 50%.

Does this raise questions about the generalisation of the velic model, if we think about serving major ports such as Singapore for example?

Yes, and that's not the only question. Sailing ships cannot carry as large a load as the large conventional container ships we know. Going beyond 200 metres for a sailing ship is very complicated.

We therefore propose more direct routes with smaller ships between regional ports. This model is advantageous in terms of inland transport because the Interland is better served. This new approach meets a need. For smaller and medium-sized players, they need systems that give independence and resilience. Velic is one of them because it doesn't require you to go to the pump to get energy, and it doesn't have any risk or negative externality. So there are a lot of benefits. Of course, the disadvantage is that there is a drop in the productivity of the work tools compared to conventional models: the ship is more expensive to buy, slower and transports a little less in relation to its length. What we are trying to demonstrate is that this lower productivity does not mean that profitability is lower too.

From a pricing point of view, how does your offer compare? Are you competitive?

In some cases, we are able to match our rates. Compared to ships of equivalent size, we manage to offer roughly equivalent transport rates, taking into account pre-carriage, which is really interesting for shippers. On the other hand, for freight that is very massive, such as containers, we are more expensive. In this case, the possible savings that we offer for pre-carriage do not make up for the difference in scale effect.

On the other hand, there is a certain predictability of prices that works in your favour?

Absolutely, this is an argument that we try to put forward to shippers. Our costs are almost independent of fuel contingencies, since only 7 to 8% of our costs are linked to fuel, whereas our competition is more like 40%-50% or even more. When the price of fuel doubles, this has a very limited impact on our model, whereas the others have no choice but to pass on the extra cost to their customers. It's an argument that doesn't have a huge response at the moment, but we think it will have an impact in the future.

Many brands have already signed agreements with your company. Can we already talk about commercial success even before the ship is in the water?

In any case, it is a sales success. Beneteau and Manitou export from the West to Baltimore, and about 30% of their exports go to the United States. It's a very important market for them as well as for us, as it has provided us with a consistent and properly remunerative backlog. Even though we are not specialised in containers, we anticipated that there would be an appetite for them as well and this was proven in 2020 despite the lockdown. We were not sure that the appetite would allow us to fight the extra cost, but the proposal of a structured offer over 13 days around two ports that are not central for container shippers, has allowed us to recover a piece of their flow to complete the France-USA load. Our challenge for the future is to complete the return from the USA to France, which presents its own challenges.

First generation Neoline pilot ship measurin 136m in length.

What is the fill rate for the first one?

Let's just say that it is now completely full, in the France to Americas direction, in terms of commitment letters and firm contracts.

So it's a great success on the shippers' side, but what are the last hurdles to be overcome before the big launch?

The maritime sector is not easy when it comes to private financing because, even if it is successful, it remains risky. The asset we are proposing to finance is less productive than the ships that exist today. But what is a decarbonised system from a financial point of view? It is a system that we are absolutely certain will cost more at the beginning and that we are promised will cost less afterwards. That's why it's more difficult to convince people, it takes time to create trust.

Should the public authorities give more support to the sector?

On a day-to-day basis, the people we work with at the institutional level are extremely involved and I must say that they develop a great deal of energy to try to ensure that the project can succeed. I thank them very much for that.

But at the political level, in the broader and nobler sense of the term, the idea would be to give ourselves the means for an ambitious energy transition. The real question is: "How do we finance these enormous efforts?" When we look at the industrial revolutions or the booms that may have occurred in a particular technology in the past, they were accompanied by extremely incentive-based public funding mechanisms... The current policies support us, but it is important to realise the difference in magnitude between what can be done today at the public level in accordance with the rules of the art, and what in my opinion should be possible given the challenges ahead. We will have to make the wine industry more widespread, and to do so, the investments will have to be very heavy.

And yet, it is right now that the game is up for the extension of the sector?

We know that the term "future generation" is no longer appropriate. More and more people are realising that the challenge is no longer to reduce emissions by 10 or 20%, but to reach zero as soon as possible. This means that velic systems have a strong case for themselves, whether as auxiliary or main propulsion systems. This growing awareness of the urgent need to act is extremely positive. Some people are working on it and making progress, such as several bankers or the European Investment Bank, with whom we are collaborating.

You mentioned a pilot ship, aren't there others in the pipeline?

Our intention is to launch a second one fairly quickly. Ideally within a year of the launch of the first one, so that we have a departure every two weeks. We would like the service to start in mid-2024. Thereafter, more specialised versions could be introduced, as well as larger versions.

Can we imagine that in 10 years' time maritime freight will be under sail? Fully?

Wind may play a role in all commercial ships, but I don't think it will be the main propulsion system everywhere, because there is no longer a single solution. The solutions that we have for main propulsion are really interesting for secondary lines and medium-sized players, because it really gives them a lot of freedom. On the other hand, for highly industrialised players, wind can only play an auxiliary role as long as the hub logic and large ships that accompany globalisation predominate.

Basically, the question behind this is that of relocation and reindustrialisation. We know very well that a post-carbon world is a world where we produce more locally, while maintaining useful exchanges of course. The objective is to stop cutting French wood to send it to China and bring it back in the form of parquet slats to sell it 50km from where it was initially cut. If in the future the focus is indeed on what needs to be transported, then the ships will be smaller and it is possible that most of them will be mainly wind-powered.

But before this logic changes, I think we should expect transport systems that are still extremely massive on major routes and that can only use wind as an auxiliary power. On the other hand, it is a positive trend that wind will clearly be used on secondary lines, which already represent a real market. As an entrepreneur, this is fine with us.

To be read also in the dossier " Decarbonised revolution on the seas"