The Fall of Hyper-standardisation

Did you know that there are more than 4,500 types of potatoes and over one thousand types of bananas on the planet? If few people can boast of having tasted more than ten varieties of one or the other, it is because today's global food system depends solely on about 150 edible plants, while there are 30,000 different kinds. In other words, we currently enjoy only 0.5% of our plant diversity! Not without consequences, society has gone through the green revolution to achieve a real standardisation of production, consumption and tastes. The current food system is reaching its limits and needs to reinvent itself to ensure the continuity of livelihoods. Seeking resilience, what models should we move towards tomorrow?

Green revolution: the race for yields

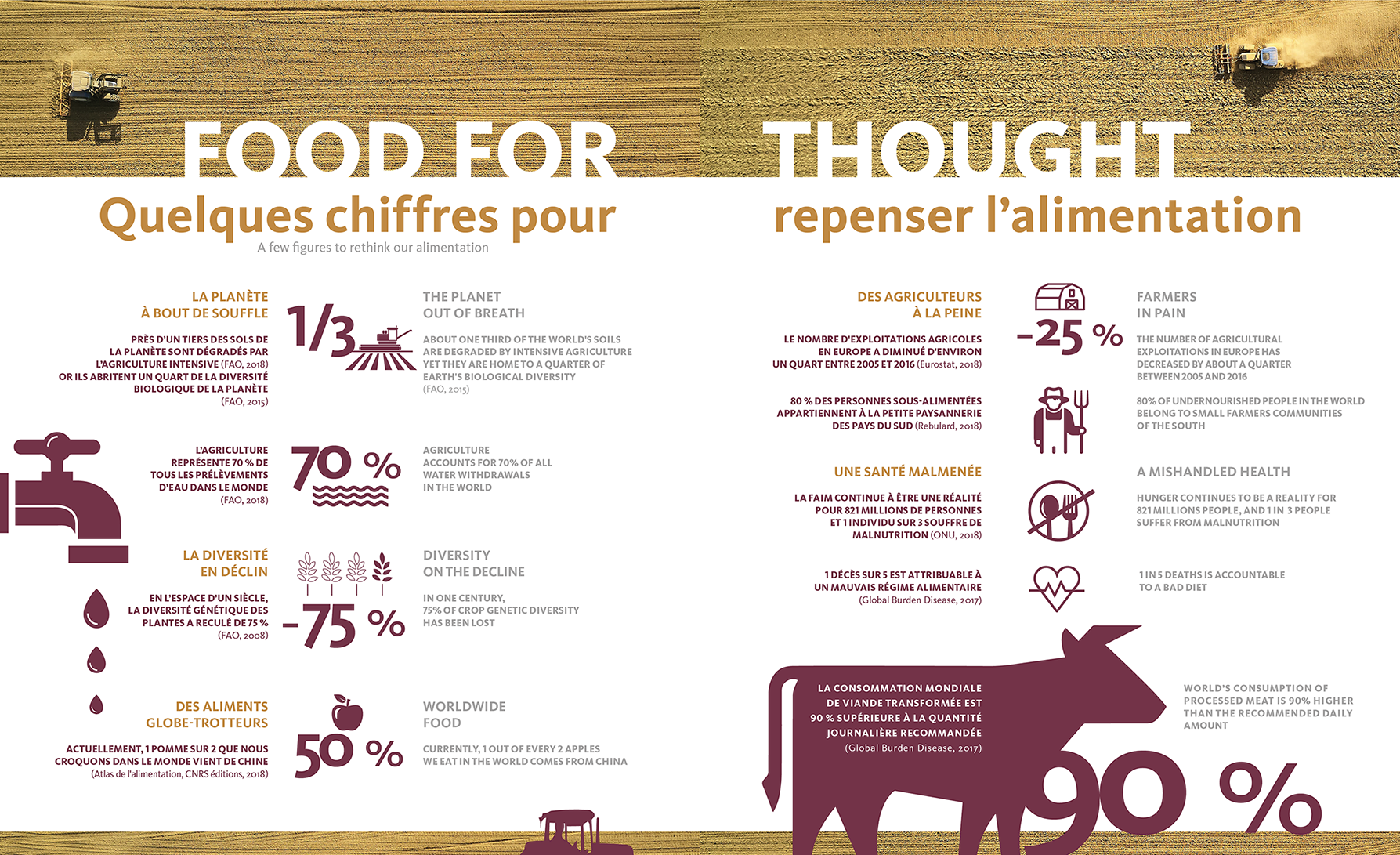

The world’s agriculture experienced dramatic increases in productivity between 1960 and 2010. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), rice yields increased by 126% and cultivated areas by 41%. For corn, the figures rose to 174% and 55% respectively. These impressive gains result from the meeting between the motorisation of agriculture and four major technical evolutions: the selection of high-yield varieties, the increased use of irrigation, the extensive use of mineral fertilizers, and the development of phytosanitary products. Within one generation of farmers, productivity has soared, reaching a ratio of 1 to 100 on some farms. It was this green revolution that gave birth to the industrialised food system we know today. As a result, Eurostat reports that the number of farms in Europe fell by about a quarter between 2005 and 2016. Over the last decade, no fewer than 4.2 million entities were wiped off the maps in the Member States to make space for vast, specialised, highly productive farms. 85% of these entities were small structures of less than 5 hectares running on mixed crop-livestock farming systems.

Far from the abundant aisles of produce from all over the world, far from the vast fields and lines of greenhouses so extensive that they are visible from the moon, the reality of yesteryear, when humankind lived from livestock breeding and local agriculture throughout the seasons is sometimes hard to imagine. Sophistication of machinery, recourse to chemical inputs, transformation, industrialisation and mass production, globalisation of exchanges. For better and for worse, changes brought by the 20th century have structurally modified our way of cultivating and consuming, now in XXL.

Indeed, throughout history, never has so much food been produced, consumed, and unfortunately, thrown away. Already in 2011, the French Academy of Sciences argued that distributed reasonably, the world’s agricultural production would theoretically be able to provide the entire population with an energy intake of 3,000 kilocalories per day. As a corollary to this change of scale, health aspects would guarantee greater product safety and traceability, leading to ever more calibrated food. An inflation of standards and a standardisation which today reveal their many limitations.

Mission: Standardisation!

In 1961, the FAO established the Codex Alimentarius to initiate the harmonisation of legislation and ensure food safety. Since then, the standards set out in this document have become international legal references in this field, notably by governing the World Trade Organization (WTO). Among the latest rules to date, there is, for example, standard CXC76R-2017 on regional codes of hygienic practice for street foods in Asia or standard CXA 6-2019, which contains the list of Codex specifications applicable to food additives. All these rules relating to transport, hygiene, packaging, display of products, and more, are initially intended to ensure increasingly safe and transparent food supply. However, at present, the picture is divided.

Food standardisation is now called into question. It is leading to an astronomical loss of biodiversity as well as to a uniformity of practices, both in terms of production and consumption methods. In the United States, 70% of the potatoes grown are of a single variety imposed by McCain for its French fries. The same is true for 60% of tomatoes, whose standard variety is imposed by Heinz. In 1903, American farmers grew 578 different types of beans. Eighty years later, there were only 32 varieties left. This decline shows in livestock farming, with no less than a third of livestock breeds now threatened with extinction, six of which are disappearing every month.

Under the pressure of open markets and increased competitiveness, farmers around the world have thus moved away from growing their many primitive and local varieties and towards genetically uniform and yield-optimised ones. As a result, supply is becoming more consistent, consumption patterns more global, cultural legacies and lifestyles are shrinking, and biodiversity is dramatically declining. The FAO reports that within a century, 75% of the genetic diversity of crop plants has been lost.

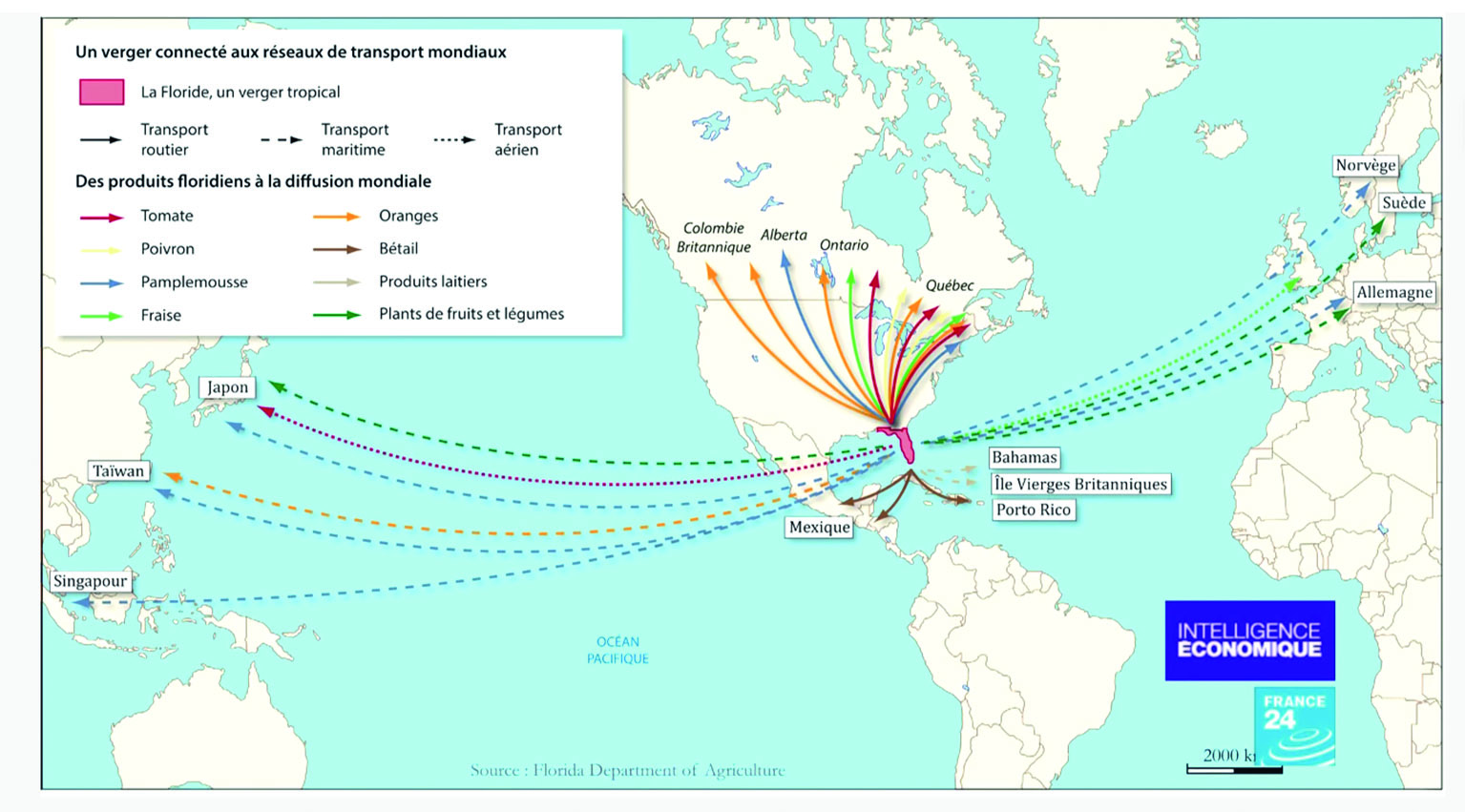

The 20th century was marked by the rise of the aeronautics sector, notably with Boeing, which has thus transformed Florida in a real-world orchard.

Fake Food and"McDonaldisation" of our habits

The "health" content of our plates, which are so similar, animates public debate daily. Foods are too fatty, too sweet, too energetic, processed with carcinogenic and endocrine-disrupting additives. Are we still moving towards a healthy diet for humankind and the planet?

According to the Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques (INSEE), the time spent preparing meals in France has fallen by 25% in a quarter of a century. This trend favors the increased commodification of processed food products and marks a growing distance between the individual and nature. This disconnection between the field and the plate leads to a significant loss of culinary knowledge and know-how among new generations. In 2010, the "Food Revolution" documentary produced in the United States, was perplexing when the famous British chef Jamie Oliver asked 6-year-olds to identify vegetables. They were unable to recognise the tomatoes in their favorite ketchup or the potatoes in their French fries. Far from the vegetable garden and the kitchen, we are now reaching the limits of a society that advocates "fake food" and "ready-to-eat".

Isn't it surprising that every year about 3.6 million Japanese households celebrate Christmas with KFC fried chicken? (*BBC, 2016). In 2018, fast food brought in more than $570 billion globally (or 512 billion euros) (*Franchise Help, 2019). The use of industrialised and standardised foods has thus increased at the expense of fresh products, resulting in more and more intermediaries between producers and consumers.

The French National Food Council tells us that 80% of food expenditure is on processed foods. What is the problem? These products share the particularity of being rich in saturated fatty acids and additives such as preservatives, enhancers, colourings and added sugars. The promotion of this diet represents health risk factors across a range of chronic diseases. Overweight and obesity, but also diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, food intolerances, endocrine disruption, digestive disorders, a list that is muchlonger than a shopping list with disastrous repercussions on the world's population.

In 2017, a study conducted by 130 researchers at the Global Burden Disease warned that one in five deaths was due to poor diet. A report by the Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition published in 2016, is not more optimistic and shows that six out the eleven mortality factors in the world are directly related to poor diet. The primary factors are excessive salt consumption, insufficient whole-grain intake and low daily fruit intake. Director of the Nutrition Department of the World Health Organization (WHO) Francesco Branca, refers to these figures as a "red flag", warning that "unless we adopt a diet that is healthy for our health and the environment, we will not get very far".

A Nutritious Desert?

Nutritional balance is essential for a properly functioning body. The varieties grown today are selected to be harvested in no time with the promise of incredible aesthetics, robustness and shelf life. The only downside: iron, calcium, vitamins and proteins seem to be on the decline. For several years now, many studies have been looking at the issue of nutrient depletion in the food we eat. From Brian Halweil's report stating that one would have to eat a hundred apples today compared to one in the 1950s to get the same amount of vitamin C, to Professor Guéguen's, who more reasonably argues that the carrot has lost 33% of its protein intake, opinions diverge and are the subject of debate.

So, what is really hiding behind the controversial phenomenon of the "empty calory"? It does not seem easy to quantify the nutrient depletion of food in a precise and unanimous way. However, several of its causes are mentioned, such as the maturity of plants and seasonality at harvest time, the average CO2 content of the atmosphere, and preservation and cooking methods. Therefore, the solution is in the hands of consumers: adopt a consumption of diverse, fresh, local and seasonal foods that are healthier for oneself and the planet!

Growing Systemic Risks

World food production and consumption are now at a pivotal point in their history. Although, they were able to make significant improvements during the 20th century, in the current context and outlook, they contain many systemic economic, social and environmental risks. FAO speaks of an "unbalanced" system with, on the one hand, "the productive potential of our natural resource base having been altered in many parts of the world and jeopardising the prosperity of the planet" and, on the other hand, "hunger that continues to be a reality for 821 million people and one in three people suffering from malnutrition".

Ecosystems on Their Knees

Over the years, the natural resources, which we underestimate, are increasingly deteriorated. The cause? Conversions in land use patterns, standardised production, overexploitation of soils, the import of invasive alien species, the destruction of natural habitats, but also pollution and climate change. The environmental impacts of the food system are disconcerting. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), agriculture, along with forestry and other land uses, accounts for 24% of greenhouse gas emissions. According to the FAO again, nearly a third of the planet's soils are degraded by intensive agriculture, and 70% of all water withdrawals in the world are attributed to it.

Faced with the startling observation of the scarcity of resources, experts are unanimous: the food system is a spectator, but above all, an actor, in a catastrophe scenario for humanity.

Profession Under Pressure

Women and men in agriculture are hard hit by the inconsistencies of the prevailing system. The question of the distribution of income from agriculture is a subject that often resurfaces in the news, but without path for improvement. This is mainly due to the rise in the prices of raw materials and energy, as well as the low remuneration paid to processors and distributors. Sadly, 80% of undernourished people today are small farmers working in southern countries (Rebulard, 2018).

In 2020, paradoxically with rising food prices for consumers, rural poverty is still a reality. The shares paid to farmers are so low that they generally barely cover production costs. Let us recall that today, according to FranceAgriMer, out of 100 euros of food purchases, only 6.5 euros are received by French producers. In industrialised countries, this situation has often pushed desperate farmers into an absurd race for gigantic farms, reminiscent of the heartbreaking scenes in Edouard Bergeon's film "In the Name of the Earth". Crumbling under the weight of debt, many farming families are now forced to give up their farms. The succession of the active and ageing population of the agricultural sector, although essential to continue feeding the world, seems challenging to ensure under such conditions.

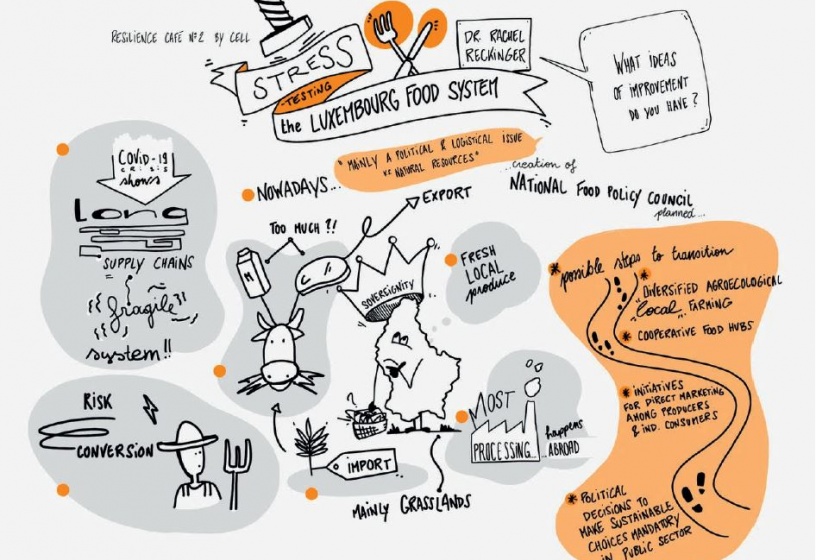

The flaws of the Current Economic Model

From production and consumption to logistics and processing, food plays a crucial role in the dynamics of the global economy. In Europe, the agri-food industry is the second largest sector in terms of turnover, with more than 300,000 companies, over 90% of which are SMEs. "Small" hitch: the economic model on which this system is based is very vulnerable, as highlighted by the recent COVID-19 health crisis. Indeed, the major difficulties that emerged from it highlighted the complexity and weaknesses of the current paradigm. Heavy dependence on trade and globalised value chains, logistical challenges, precarious labor, indebtedness, considerable lack of diversity in production and outlets... Our food system is in peril.

Pathways to Resilience

Given the current challenges, the observation is unequivocal: the world food model needs to be redefined to become more coherent, efficient and sustainable for the future of humanity. According to UN forecasts, in a little less than 30 years, close to 10 billion people will have to share the planet's resources. But today, the conditions that allowed our post-industrial food system to prosper can no longer be guaranteed. More importantly, they must be banished because they contribute to the worsening of threats to food security. The agricultural sector thus seems to be caught in a vicious circle of which it is both the executioner and the victim. The complex and interdependent links in the food chain are vulnerable to changes and disruptions. Expanding the current model would entail enormous risks. So, what are the solutions for tomorrow?

Diversity: The Key to Food Resilience

First and foremost, there is diversity at all levels. On the agricultural side, it is the diversity of production, farming practices, stakeholders and their interactions is paramount. The idea: moving away from intensive monoculture systems that are more vulnerable to shocks. Varietal diversity is also essential. A broader range of seeds planted makes it possible to better adapt to the climate, soil types, fluctuations in external conditions (weather, pests, selling prices) and to each farmer's farming methods and means of cultivation.

At the regional level, diversified agricultural sectors are fighting preventively against the risk of epidemics or sectoral crises. At the national level, diversified production makes it possible to stem the severity of shortages, stimulate the economy and strengthen the power of stakeholders. According to the FAO, "the conservation and use of a wide variety of animal and plant species is the key to ensuring the adaptability and resilience of populations to climate change, emerging diseases, pressures on water supplies and volatile market demands”. Also, the exploitation of ecosystem services reduces the need for external inputs and improves the efficiency of output. Diversity, therefore, seems to be the keyword for tomorrow's agriculture.

Along with this need, the construction of sustainable food also requires the involvement of society. Energy suppliers, transport companies, the secondary and tertiary sectors, public authorities, civil society and consumers: all are architects of this change of model. The transition from energy resources to the multitude of options offered by renewable energies, changes in consumption habits, diversification of producers: the aim is to decentralise and reduce dependence between the links in the supply chain in order to promote a modular and heterogeneous system based on a holistic approach to food.

Building a Society Around Food

This includes strengthening the autonomy of the actors in a territory. By this, we mean the power of farmers to dispose locally of the means of production, processing and marketing of their products. As for the territory's inhabitants, it is also about being able to meet their needs close to home. It is on these principles that the concept of "reterritorialisation" or "subsidiarity" of the food system is based. This approach is intended to re-humanise, promote social ties and boost rural development to create jobs and achieve a more stable economy that is less dependent on international markets. To support this model, the FAO stresses that investment is essential in infrastructure such as transport, telecommunications and storage facilities.

Paradoxically, if the need for regionalisation of production and consumption chains is established for greater food resilience, a part of globalisation also has a role to play so that humanity can have robust safety nets for the challenges ahead. For a good reason: climate change is expanding drylands, causing natural disasters and making weather conditions for arable farming more unstable. In view of these prospects, many regions may no longer be able to achieve food self-sufficiency. This is already the case for parts of North Africa and the Middle East. Asia is also increasingly exposed. For these regions, international trade is essential to meet the needs of local populations.

More than the question of globalisation or regionalisation of agriculture, it is production methods and consumption behaviors that need to be reviewed for a change in the food paradigm.

Thus, on the road to resilience, humanity faces many challenges. One of the main ones is at the crossroads between the imperative of feeding a growing world population, reducing the ecological footprint and preserving natural resources for future generations. Quite a puzzle! Our industrialised society today seems particularly vulnerable to the occurrence of severe disruptions such as health and financial crises or natural disasters. As a sign of hope, many inspiring solutions already exist towards the great quest for food resilience. If these paths are ignored, how long before the balancing act of the global food system collapses?

To be read also in the dossier "The Food To Come":