The Great Green Disarray

More numerous than ever, they are knocking on therapists’ doors, their minds heavy with an emerging ailment. Anxiety pegged to their body, they say they no longer know how to live with this environmental question haunting them. The magnitude of the challenge has become part of their daily lives. They cannot project themselves into a future that they can no longer serenely foresee. This emerging and growing phenomenon, commonly referred to as eco-anxiety, is defined by the American Psychological Association as "chronic fear of environmental disaster". Today, we face a major challenge: how to overcome this tetany spreading among the population? How to transform these emotions into a movement that meets the challenge?

While not everyone will consult a doctor, the phenomenon is, in fact, widespread, particularly among the young population. A study published last year by The Lancet Planetary Health, involving 10,000 individuals aged 16 to 25 in ten different countries, reveals a strong statement. It reports that 84% of those surveyed said they were affected by anxiety when considering climate challenges. Nearly 60% of respondents declared themselves to be 'worried' or even 'extremely worried', and 45% claimed that this apprehension was negatively affecting their daily lives.

The phenomenon is global. Far from a concern that would be the prerogative of populations living in rich countries, the study reveals, on the contrary, that the level of anxiety is generally higher in poor territories directly impacted by climate change.

This distress is often a psychological response to environmental transformations that have already been at least partly experienced. In this regard, the term eco-anxiety is insufficient to designate this state, as it is defined as anticipatory anxiety and described by certain psychiatrists, such as the American Lise Van Susteren, as a prospective trauma or "pre-traumatic stress disorder". It is worth supplementing it with the concept of solastalgia, which covers psychological distress when facing a deterioration, this time experienced, in one's environment. This neologism, invented by the philosopher Glenn Albrecht (see our interview on page 45), refers to the "feeling of desolation caused by the devastation of one's habitat and territory". As he reminds us in his latest book, Earth Emotions, it is "the homesickness you feel when you are still at home".

This feeling of loss of a beloved place can also be experienced by individuals who are not locally impacted by these transformations but who have a consciousness of the degradation of the biosphere as our great common home. It is thus not surprising that people committed to sustainable development, who are particularly aware of the planet's deterioration, are more prone to solastalgia. A 2021 study conducted on climate scientists entitled "Climate emotions: It is ok to feel the way you do" highlights the real risk weighing on the mental health of this population. Burnout, anxiety, and even grief-like emotions related to climate change were reported.

Given the abundance of information on the topic and the increasingly urgent reports from the IPCC and IPBES, it is becoming difficult - for specialists and the public alike - to escape this XXL-sized awareness of our vulnerability.

A pathology?

If this distress is real, does it qualify as an illness? No, according to the specialists. It does not result from a psychiatric disorder but an advanced awareness linked to a strong sensitivity to the topic. The reaction is actually quite logical when confronted with such a widespread observation. From this point of view, it is instead the 'eco-indifference' that should be considered abnormal. However, this distress can cause considerable suffering and may sometimes require specific psychological support. Panic attacks due to the profusion of products offered in a shop, renouncing plans to have children, ending relationships with certain relatives, depression... The effects induced by this anxiety can be severe.

We must therefore work collectively to improve our psychological resilience. Accepting that the world's upheavals generate emotions, understanding them and letting them evolve to act.

Plural emotions

Charline Schmerber, a psychotherapy practitioner, has studied the expression of this ecological discomfort through the testimonies of more than 1,200 people. She sees an anxiety that she describes as systemic, extending from the intimate sphere to the geopolitical dimension. The multiple climate change impacts and environmental degradation are a matter of concern. The five most-cited risks are war, food and water shortages, violence, economic and health deterioration. The idea of a global collapse is also sometimes raised by participants.

A range of low emotions comes with this anxiety: sadness, anger, feelings of helplessness and even guilt. People go through distinct phases, which are similar to the mourning process. After all, it is about dealing with the loss of a world. "The world as we know it today will change," says Charline Schmerber. "The psychic integration of this reality leads most people to go through a mourning process." As she explains, "the first phase is characterised by an attitude of withdrawal and by a look towards the past, towards what has been lost, tainted. Various stages are attached to this downward phase: denial, anger, bargaining, and sadness. A second, ascending phase then follows, in which life energy is contacted, which allows the individual to move again: acceptance, forgiveness, search for meaning, serenity and regained peace." It remains to be able to overcome this second stage and consequently break free from the tetany and despondency in order to take action.

The powerlessness lock

Feeling powerlessness is a recurring feature of solastalgia.

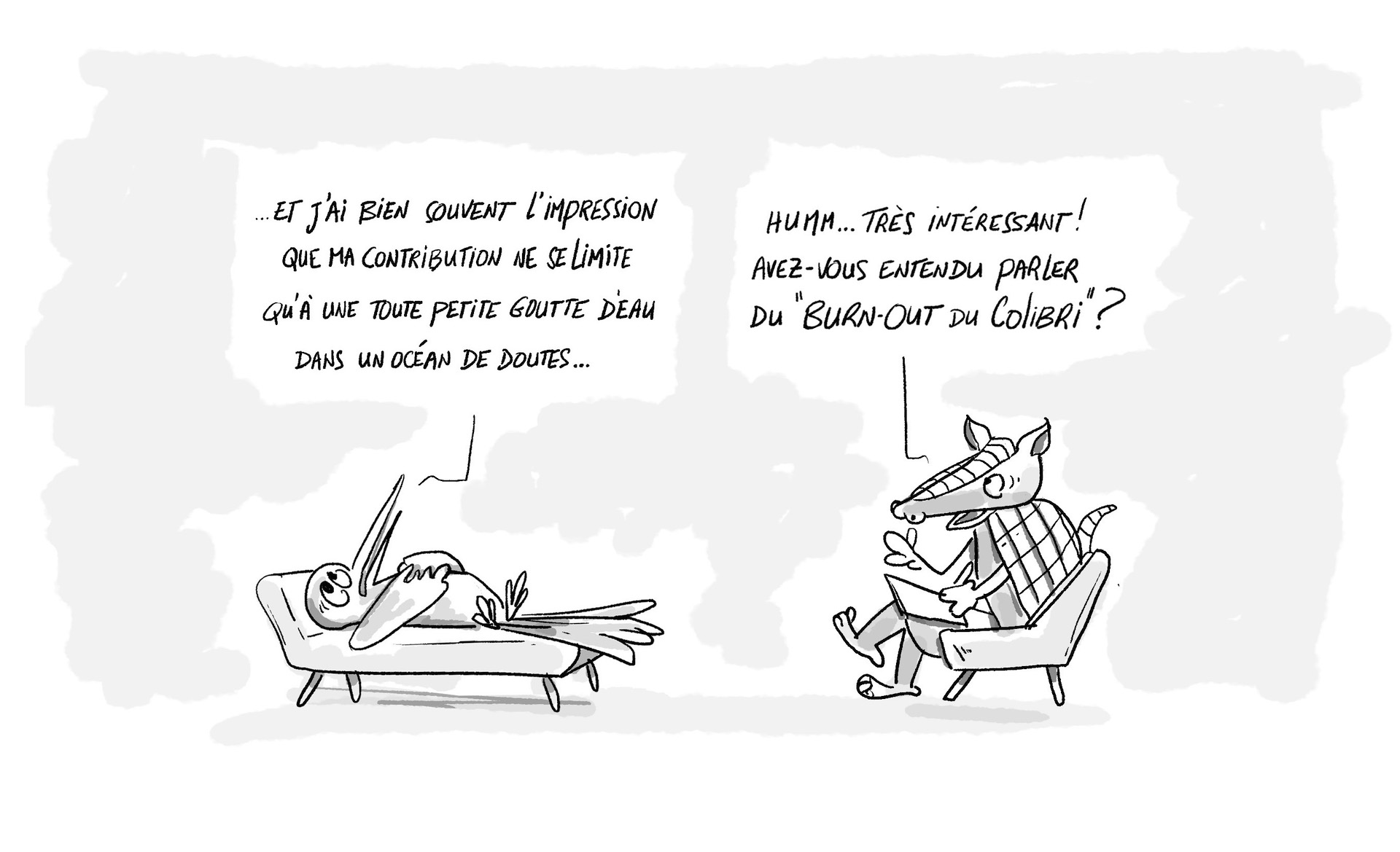

In the view of an eco-anxious individual, the small daily actions taken to preserve the planet often become derisory given the magnitude of the phenomenon and the political or economic forces overwhelming them. Given that my effort does not really change the course of events, what is the point? This refers to the famous notion of powerlessness described in neuroscience.

Yet many people have devoted considerable effort to personal action, increasing the number of small gestures that matter, such as the famous legend of the hummingbird taken up by author Pierre Rabhi, where the bird "does its part" carrying water in its beak to extinguish the forest fire. Relentlessly, they sift through each and everyone of their daily habits to make them as green as possible, a constant exercise that sometimes turns into an obsession. However, this quest for eco-perfection leads straight to exhaustion and general despondency. So many efforts deployed to achieve an impact that is considered tiny to what is at stake... This is precisely what the blogger Justine Davasse, who started an online discussion group on solastalgia, calls "the hummingbird burn-out".

This lack of sufficient impact at the individual level therefore leads to expectations turned towards the collective level. Again, it is the overall powerlessness of society that is pointed out. Looking to systemic change, the inaction of the leading classes is regularly criticised, with great frustration linked to the lack of political decision-making on the matter. The Lancet Planetary Health study cited above states clearly: "Climate anxiety and distress were correlated with perceived inadequate government response and associated feelings of betrayal." Nearly two-thirds of the young people surveyed think that the authorities are not doing enough regarding the environment, and 58% of them consider that they have betrayed the new generations on this topic.

Confronted by this total lack of control and widespread powerlessness - 56% of young people feel powerless to address the environmental question - how can we restore confidence? How can we regain faith in the beneficial capacity of Man and transform these emotions into power for action?

From asthenia to motion...

The task is not simple. It involves overcoming a strong dissonance: the staggering idea that humans are self- destructing.

This requires a realignment on several levels: our perception of ourselves and our actions as individuals, our role within the collective, and finally, our place within the biosphere. All in all, it is the exercise of a great reconciliation.

Reconciling with oneself is the first step. We need to leave behind our schizophrenic relationship with the world, where our actions do not reflect our convictions and live by our values. However, the challenge for many eco-anxious people does not lie there, as their behaviour is generally quite respectful of the environment. Instead, it requires a dose of self-care and self-gratitude! Recognising that the actions taken on a personal level are not futile or meaningless. Acting in the present and not projecting oneself into the anxiety-inducing horizons of 2050 or 2100. In a nutshell, to be at peace with oneself and admit one's modest positive impact.

Hence, even on a small scale, actions must be valued as they constitute a strong antidote to solastalgia. In the United States, Isabel Grace Coppola's recent work at the University of Vermont, entitled "Eco-Anxiety in 'the Climate Generation': Is Action an Antidote?" demonstrates this: "It appears that recognition of one’s spheres of influence is vital to long-term coping and resiliency."

Reconciling with the collective is also imperative. The human being is not the great enemy to be destroyed, but it is part of the solution. Collective powerlessness and guilt must be replaced by a feeling of usefulness: How can I be part of a constructive approach to these challenges? What is my role, and what positive impact can I have within a sustainable society? The link between the individual and the collective is key to making the notion of society meaningful. Several forms of collectives can be reinvested. Companies, in particular, play a decisive role as they can contribute to the answer by making work meaningful. They also possess the advantage of being a force that drives the collective on an appropriate scale. Beyond the gigantic scale of states or the weak impact of small, isolated initiatives, companies embracing all their employees and stakeholders have the potential to leverage powerful change. Thriving initiatives such as the international B Corp movement, the so-called "Companies with Missions" and the "Companies and Poverty" Action Tank in France, or the Yunus Social Business in Germany, are federating ambitious strategies in this field. Cities and municipalities also represent successful territorial scales where results are more easily observed and where the collective can be fully expressed without being diluted. These structures are key environmental action areas for implementing change at a level other than that of the individual or the state, and thus creating a more tangible hope for a common movement.

Finally, and most importantly, reconciling with the natural world. We collectively face what the American ecologist Robert Pyle refers to as the "extinction of the experience of nature" or a "nature deficit". Yet this disconnection is the root of our torments. Firstly, because this distancing has encouraged behaviours of control and predation on our environment, inspired by an illusion of power and superiority over nature. Secondly, because it gives us a sense of well- being! This is something we had somewhat forgotten.

In his book published this year, Cerveau et nature, the neuroscientist Michel Le Van Quyen describes the restorative capacity of nature on our physical and mental health. The presence of trees, the silence of the mountains, the rhythm of the waves, the smell of the earth... the physiological, cognitive, and even psychological impacts are unexpected. Far from being esoteric, this field of scientific research is booming, and the benefits of being in contact with nature are regularly identified. For instance, scientists at the University of Michigan in the United States have clearly documented the reduction of stress biomarkers. Canadian biologist Rachel Buxton also demonstrates that nature sounds positively impact cognitive performance and pain sensitivity. A study conducted on schoolchildren in Barcelona even identified an increased attention span and IQ when being exposed to green spaces.

Another exciting field of current investigation in integrative medicine is the link between nature and our microbiota, with impacts on physiological and psychological health. Concretely, Mathew White, a British researcher in environmental psychology at the University of Exeter, has attempted to evaluate the dose of nature that can significantly contribute to better physical and psychological health. The result: at least two hours a week in green spaces. The time has come to "revitalise our brains, which are tired of too much artificiality", says Michel Le Van Quyen. This is the call that 26 scientists co-signed in Science in 2019, with an article entitled "Nature and mental health: an ecosystem service perspective". This is precisely the ambitious mission of the Université dans la Nature, founded in Canada and recently implemented in Luxembourg, which aims to reconcile Man with its environment (see our interview on page 65).

Ceasing the dichotomy between Man and nature is thus beneficial for our well-being and a way to revisit our emotions positively... But there is more. Fundamentally, and this is the good news, this restored closeness to nature leads us to adopt a more protective behaviour towards the environment and consequently, act. As pointed out by the philosopher Cynthia Fleury and the ecologist Anne-Caroline Prévot in their book Le souci de la nature; "Knowing is obviously not enough. We need real-life situations. Experience."

A study conducted on 20,000 people in the United Kingdom and entitled "Nature contact, nature connectedness and associations with health, well-being and pro-environmental behaviours" demonstrates that frequenting nature (at least once a week) is positively associated with health and pro-environmental behaviours of individuals. A society more exposed to nature will be more inclined to take action to preserve it. The researchers conclude that: "Interventions increasing both contact with, and connection to nature, are likely to be needed in order to achieve synergistic improvements to human and planetary health." As the two are mutually dependent. Human health and ecosystem health are interconnected. There is a continuum of life, and the time has come to regain our place, and hence our role, in the world. Much is at stake.

of young people say they are "worried" or even "extremely worried" about the climate and environmental question and 76% find the future worrisome

do not longer trust Governments regarding the climatic question

are reluctant to have children

(Source : Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, déc 2021.)