The ocean plays a crucial role in climate regulation, biodiversity conservation and the supply of resources for the global economy. Protecting it is, therefore, an essential priority, especially at a time when anthropogenic pressures are intensifying and jeopardising the health of marine ecosystems. Today's threats to this biosphere make it a real time bomb. We must understand these phenomena better to protect the oceans more effectively.

Oceans threatened on all sides

Marine biodiversity is under threat, and a growing number of reports are alarming. The Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity (IPBES) has classified 66% of marine ecosystems as being severely degraded. Last February, the United Nations declared nearly half of all migratory species to be in decline and over 20% on the brink of extinction. In this edifying assessment, the most worrying threat is to migratory fish, with 97% of species on the verge of extinction. This drop in biodiversity is a clear sign that the environment in which these species evolve is undergoing unprecedented mutations, bringing it to the brink of collapse.

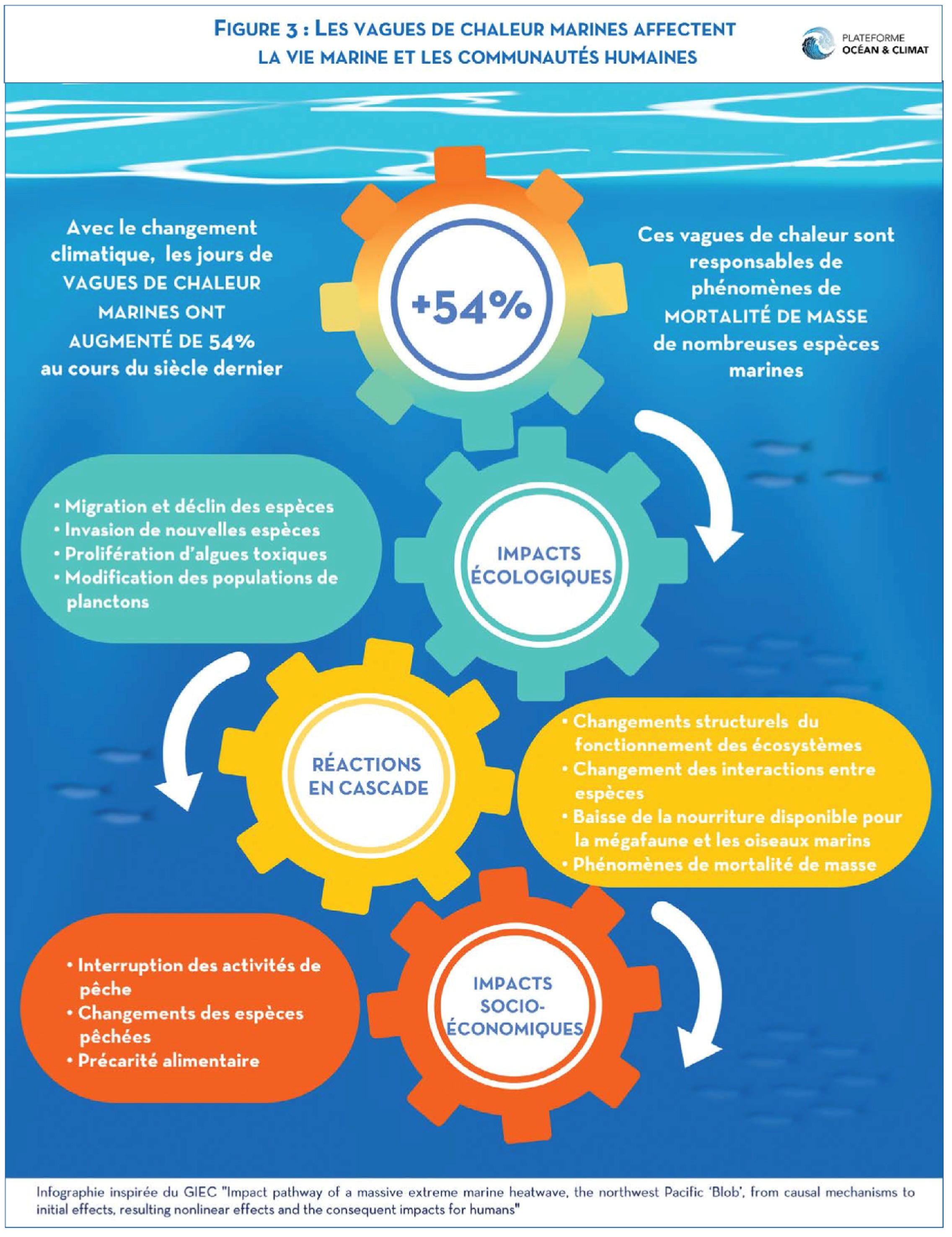

The first observation is the significant warming of the oceans. Marine ecosystems absorb over 90% of the excess heat generated by the greenhouse effect. As a result, the average temperature of the ocean surface - between 0 and 75 m deep - has increased by 0.11°C per decade since the 1970s. And the pace is accelerating: since 1990, the rate of ocean warming has more than doubled, according to the IPCC. The phenomenon is particularly acute in the Arctic, where surface air temperatures are rising at around twice the global average, accelerating the process of sea-level rise. A worrying fact is that marine heat waves have increased by 54% in a century. These episodes are not only conducive to extreme events, but also constitute real tipping points, leading to mass mortality of many marine species, such as corals and kelp forests.

Photo : Pixabay

Warming of the oceans promotes the development of invasive species such as algae and jellyfish.

In oceanic processes, currents play a crucial role in regulating temperature and carbon proliferation. However, climate change is disrupting these processes, leading to ocean-level stratification and a loss of oxygen (see our interview with ocean and climate expert Prof. Hans-Otto Pörtner).

The marine environment is responsible for half of the planet's oxygen production, but over the past 50 years, global oxygen levels have fallen by almost 2%. According to a study by Shanghai University, deoxygenation signals could appear in 72% of the world's ocean areas by 2080 (Hongjing Gong, Chao Li, Yuntao Zhou, 2021). This phenomenon of hypoxia is reinforced by excessive nitrogen and phosphorus inputs from wastewater treatment plants and agricultural inputs, otherwise known as eutrophication. Today, scientists fear that deoxygenation could modify the nitrogen cycle, resulting in the emission of nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas whose potential impact is 300 times greater than that of carbon dioxide. A real time bomb...

Another worrying phenomenon is ocean acidification. This has increased by 26% compared to the pre-industrial era, and some models predict a 150% increase in acidity by 2100. The oceans are a powerful carbon pump, and the dissolution of CO2 in seawater causes a drop in pH, i.e. acidification of the environment. This, coupled with a reduction in the quantity of carbonate ions, is particularly damaging for marine plants and animals with skeletons, shells and other calcareous structures. In addition, several studies show that the altered chemistry of the oceans will ultimately reduce their function as carbon sinks, leading to potential feedback loops in the climate-carbon cycle system and thus accelerating climate change.

In addition to these threats, all recognised as being of anthropogenic origin, there is also pollution more directly attributable to humans, exerting unprecedented pressure on the oceans. Sewage, pesticides, heavy metals, antibiotics, hydrocarbons... the list of pollutants released into the marine environment is quite long. Plastic pollution is undoubtedly one of the most visible, with up to 17 million tonnes ending up in the sea within a single year. That's more than a tonne of plastic waste dumped into the oceans every three seconds. Plastics comprise the bulk of marine litter, accounting for 85% of the total.

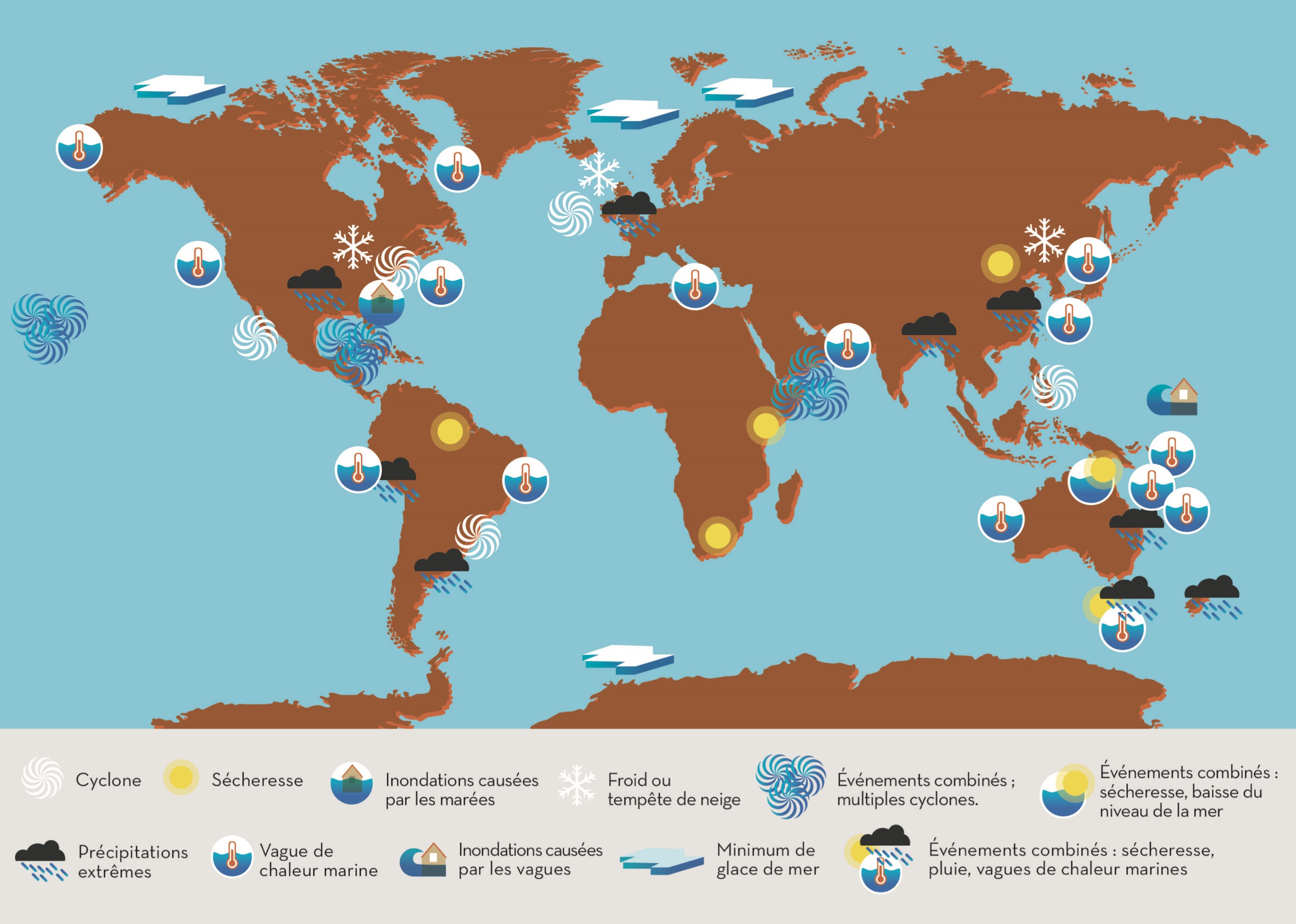

Regions where extreme events related to changes affecting the ocean have occurred (Source: IPCC, SROCC, 2019).

According to the SeaCleaners organisation, over 1.5 million marine animals die every year, and 90% of marine species are affected by this pollution, from cetaceans to plankton. As a reminder, 32% of manufactured plastics still end up in nature, particularly in the ocean. In addition to chemical pollution of the oceans, noise and light pollution are also being blamed. Noise from shipping, drilling and other seabed exploration activities interferes with natural sounds. Cetaceans, which use the same frequencies to orient themselves, feed and reproduce, are particularly affected. According to a study, the range of blue whale songs has been reduced by 90%.

Another particularly impactful anthropogenic pressure is the extraction of ocean resources, from rare metals to sand, including living resources and, of course, overfishing. According to the FAO, 34.2% of the world's fish stocks are depleted or overexploited, 43% in the North-East Atlantic and 83% in the Mediterranean. This depletion of fish stocks is a food security issue in many parts of the world. The factory ships practices are particularly contested. Pelagic mega-trawlers, real titans of the seas measuring up to 145 meters in length, can catch up to 400 tonnes of fish a day, an equivalent of 1,000 small-scale fishing vessels.

Last but not least, coastal and marine tourism exerts considerable pressure on already substantially weakened aquatic ecosystems. Overfrequentation of tourist sites, residual waste dumping and damage caused by nautical activities threaten marine biodiversity and coastal ecosystems. To mitigate these impacts, increased tourist awareness is essential to encourage respect for marine flora and fauna, protect sensitive sites and promote responsible tourism.

Overexploitation of sand According to the United Nations Environment Programme, 50 billion tonnes of sand and gravel - one

million 15-tonne trucks a day - are extracted worldwide yearly. Used in construction, digital materials and glass production, sand is the world's second most important resource after water. Dredging operations lead to the destruction of biodiversity habitats, coastal erosion and the salinisation of aquifers, threatening the water table. The UN warns of this phenomenon and calls on industries to implement circular processes to avoid overexploiting this strategic resource.

Overexploitation of sand According to the United Nations Environment Programme, 50 billion tonnes of sand and gravel - one

million 15-tonne trucks a day - are extracted worldwide yearly. Used in construction, digital materials and glass production, sand is the world's second most important resource after water. Dredging operations lead to the destruction of biodiversity habitats, coastal erosion and the salinisation of aquifers, threatening the water table. The UN warns of this phenomenon and calls on industries to implement circular processes to avoid overexploiting this strategic resource.

Better understanding

As UNESCO reminds us, "to address global issues and ensure the sustainable use of marine resources, data-driven research, conservation and management of the oceans are essential." A better understanding of the oceans' treasures is also the ambition of the "1 OCEAN" scientific exploration project founded by the international organisation and deepsea photographer Alexis Rosenfeld. The objective is to record the oceans’ wealth, explore the environment and understand it through science (phenomena, ecosystems, species), and create emotion by inspiring wonder in as many people as possible to encourage everyone to preserve the ocean.

Understanding the oceans as a whole remains complex. However, a better understanding of these mechanisms would enable us to anticipate climate variations better and more accurately assess the impact of human activity. This is why Mercator Ocean International (MOi) has been developing numerical ocean analysis and forecasting models for over twenty years. Its new objective is to develop the ocean's digital twin. According to MOi, this involves "providing a coherent, high-resolution, multidimensional, near-real-time virtual description of the ocean. This includes its physical, chemical, biological and socio-economic dimensions." This decision-support tool will enable precise diagnosis and identification of best practices and solutions, thanks to satellite data, thousands of sensors, and the support of artificial intelligence.

Towards systemic protection?

International frameworks exist to protect ocean ecosystems and atmospheric processes under anthropogenic pressure. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) forms the legal basis for ocean law. The United Nations' Sustainable Development Goal 14, adopted in 2015, reiterates the ambition to "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development". The aim is to place ocean governance at the centre of the dialogue.

In addition, the UN proclaimed the Decade of Ocean Sciences for Sustainable Development (2021-2030) to preserve the marine realm. More recently, in June 2023, after 18 years of negotiations, the 193 member states adopted a historic agreement: the International Treaty on the Protection of the High Seas. It aims to protect the marine environment beyond the national boundaries initially covered by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This treaty is an opportunity to turn the ambitions of the Kunming-Montreal Agreement into reality by creating a tool for achieving the conservation objectives of protecting at least 30% of our planet by 2030 (the 30X30 target). However, these declarative advances need to be implemented on the ground, and many voices are being raised to denounce highly theoretical marine protected areas (MPA). "Of the 10,000 or so marine protected areas existing worldwide, many are only on paper," points out the Ocean & Climate platform. "One of the main difficulties in running a network of MPAs is their governance and co-management between public players, professional sectors and sea users." A study published in 2024 by the oceans protection association Bloom questioned the effectiveness of MPAs, establishing that trawling is practised in 60% of these supposedly protected areas in Europe. The third United Nations Conference on the Oceans will be held in Nice in June 2025, jointly organised by the governments of France and Costa Rica.

Did you know?

As a result of intensive hunting, oil exploitation, chemical and noise pollution, and intensive fishing for krill, the whale's primary source of food, a total of 70% of blue whale populations have become extinct in just ten years. It is still hunted in Norway, Japan and Iceland.

(Source: Conservation Nature)

It will be an opportunity for States to clarify the protection they intend to give to the oceans, and particularly to the notion of strict protection for MPAs. The "Starfish 2030" mission, via the Horizon Europe program, aims to maintain and restore the health of the oceans, seas, lakes, rivers and streams to build a more ecological blue economy.

Beyond national governments, the protection of ocean ecosystems requires us to rethink our economic model to preserve marine resources: non-depletion of stocks, precautionary principle with regard to the seabed, circular economy to limit waste, and reduction of emissions... these are just some of the avenues to be followed by businesses to move towards a sustainable blue economy (see our article on page 99). Citizen involvement can also make a real difference in protecting the oceans by reducing plastic consumption, choosing responsible fishing, participating in beach clean-ups or supporting environmental organisations. Citizen movements and community initiatives are powerful levers for raising awareness and mobilising the population.

Making a collective commitment to preserving these vital ecosystems makes it possible to influence political and industrial decision-makers. Protecting the oceans is an urgent and complex challenge requiring a holistic and collaborative approach. Whether we live in coastal or landlocked countries, every one of us has a crucial role in preserving these marine treasures. Only a concerted and determined effort will ensure a sustainable future for the oceans and future generations.

To be read also in the dossier "Seas at risk":