Interview with Hans-Otto Pörtner

"These are laws of nature that we need to respect"

A leading expert in marine biology, Hans-Otto Pörtner warns of the dangers facing the oceans. He tells us what needs to be done to preserve this essential ecosystem.

Interview

Sustainability Mag : Your work was rewarded last year with the Planetary Health Award. This award recognises the progress you made with the working group you led at the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) on the impacts of climate change, adaptation, and vulnerability. Also, it highlights the importance of your work on the oceans. Is this a sign that the topic of the oceans gets more attention?

Hans-Otto Pörtner : I would hope so. Certainly, the interest in ocean matters was strengthened during the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Cycle, and we were able to compile a special report that brought ocean and cryosphere issues together. There were quite a few government delegations in the IPCC plenary supporting such a special report and I had the privilege to lead the effort. The increase in interest is also visible in the UNFCCC (United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change). We now have an Ocean Dialogue where ocean matters are being discussed during each intermediary meeting and during the main Conference of the Parties (COP). The last one was in Dubai with an ocean pavilion and related activities. So, this is truly a positive development, and I hope that it will become routine to have ocean questions addressed.

Hans-Otto Pörtner - IPCC

Let us hope so, indeed, as the situation is critical. How would you describe the major impacts of climate change on the ocean’s ecosystems?

There are some impacts where the ocean changes are directly coming back to us. With a warming ocean, the hydrological cycle is intensifying. We observe an interaction between land, atmosphere and ocean that is bringing more humidity into the air. This means we have higher intensity of extreme events such as storm surges and so forth.

The expansion of the warming ocean is also contributing to a rise in sea level, up to about 0.3 meters by 2100. In addition, the melting of the ice shelves drives sea level rise and is happening at a faster pace than before, and the situation seems to be riskier than we evaluated in the special report on the ocean. Recent evidence indicates that even with 1.5-degree global warming, we are now moving towards 7 metres of sea level rise, which will challenge many coastlines. For small islands, it is a matter of existence. So, this is what is directly coming back to us from the ocean.

Then, we need to consider the impacts of climate change on ocean ecosystems. There are three major climate drivers: warming – the ocean takes up more than 90% of the heat of the planet –, CO2 entry – it takes up about 30% of the CO2 emissions – and stratification. The warming ocean is stratifying over larger areas, expanding North and South from low latitudes with warm ocean layers that are floating on the cold ocean underneath. This means that the exchange of gases between surface and deep water will be restrained, and that the biological activity will consume more oxygen at the intermediate layer. Consequently, we observe a stronger expression of oxygen minimum zones at this depth level. At the same time, our nutrients and outputs due to our agricultural fertilising practices get into the rivers and then into the coastal oceans. This leads to the formation of oxygen-deficient waters. This hypoxia can become so severe that there is no animal life possible anymore.

These three challenges, warming, acidification and oxygen loss, are strongly affecting marine life, especially where the three drivers come together. Some large-scale observations and the increasing occurrence of heatwaves currently indicate that temperature is still the main driver of change in the ocean.

How was 2023 in that respect?

2023 was an extremely warm year, and ocean warming was a big part of this. This is a record year in which ocean temperatures have moved beyond the continuum of warming that we have seen to date. 2023 is a strong signal of the acceleration of global warming that we are currently experiencing.

Does this mean that certain species are moving to escape from areas that are too hot or lack oxygen?

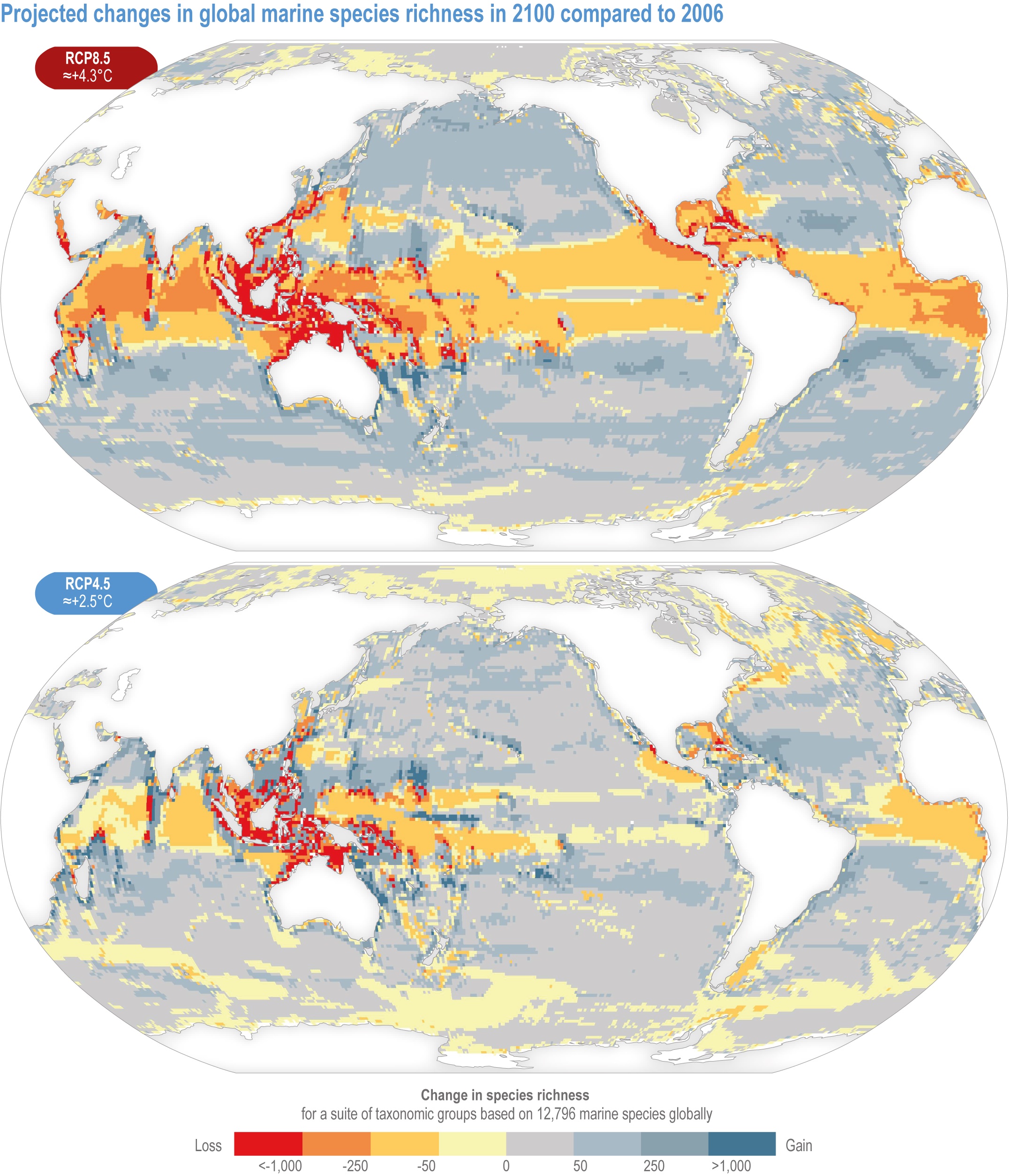

Indeed, animals are moving out of their usual zone and are trying to follow their preferred temperatures. This includes fish, invertebrates, plants, zooplankton and phytoplankton species which are also moving to higher latitudes. The plankton found in the warmer waters will show reduced body sizes and reduced biomass. At low to mid latitudes the productivity in surface water is reduced as the stratification of the ocean prevents the minerals that are important for the growth of marine photosynthetic organisms from returning to the surface. Larger ocean parts literally turn into a desert because their productivity is decreasing.

Species are moving North and South, and interestingly, we see a marine animal biodiversity valley in the tropics around the equator. This picture reflects that the highest temperature tolerances of plant and animal life are being reached in the warming oceans and that these organisms are vulnerable to further warming.

With continued global warming, habitats are lost in the ocean and on land. It should be noted that this is also true for human habitat. The combination of heat and humidity for humans and other mammals on land is becoming so bad in the lower latitudes that lethal environmental conditions form in some areas during heat waves. This may elicit a shift in the biogeography of our own species. We are part of this overall evolutionary picture: we cannot exclude ourselves, although we would like to.

Latitudinal shifts in marine species richness illustrate the responses of species to global warming.

The depletion of biodiversity in certain waters also raises the question of food security in these regions...

Yes, some areas, like parts of the Mediterranean Sea, face such challenges. The situation there is particularly problematic since the organisms cannot move North as they can in the open ocean. Aquaculture is also impacted by climate change. For instance, in Greece, mussel aquaculture is already at risk in shallow lagoon-type ecosystems. There, the heat waves are stronger and mass mortality has been important during recent years. This indicates that there are places where traditional economic activities, like certain aquacultures, may no longer be possible. As a consequence, people will need to change their economic model.

According to you, what are the priority actions for the ocean?

The priorities I see are as much for the ocean as for the land.

First, we must intensify our effort to curb emissions within a time window of 10 to 20 years and be successful in reaching net zero. We must achieve net zero by mid-century at the latest to minimise the degree of global warming and unfortunately, we must now say, to minimise the overshoot, as we will probably not be able to stop global warming at 1.5. degrees. This threshold will probably be surpassed, and we all hope that ecosystems will be resilient enough. Today, this is an open scientific question. What damage will this overshoot cause?

Second, and at the same time, we must protect our ecosystems. I see a strong connection between climate and biodiversity. In the long term, we will rely on healthy ecosystems to help bind CO2 that we cannot cut by emissions reduction and store it away in forest biomass or sediments on land and in the ocean. Conserving carbon-rich sediments and carbon-rich habitats such as saltmarshes and mangroves is a priority. However, ecosystems on land and in the ocean are so vulnerable to climate change that they may lose the capacity to help the planet in the long term. We see that already unfolding in the tropical forests on land, and we observe a loss in productivity in the ocean. This is a big concern that should stimulate us to minimise global warming.

Hans-Otto Pörtner with Debra C.Roberts, co-Chair of the IPCC Working Group II

Today, less than 10% of the oceans are protected. How much of the oceans do you think should be covered by conservation measures?

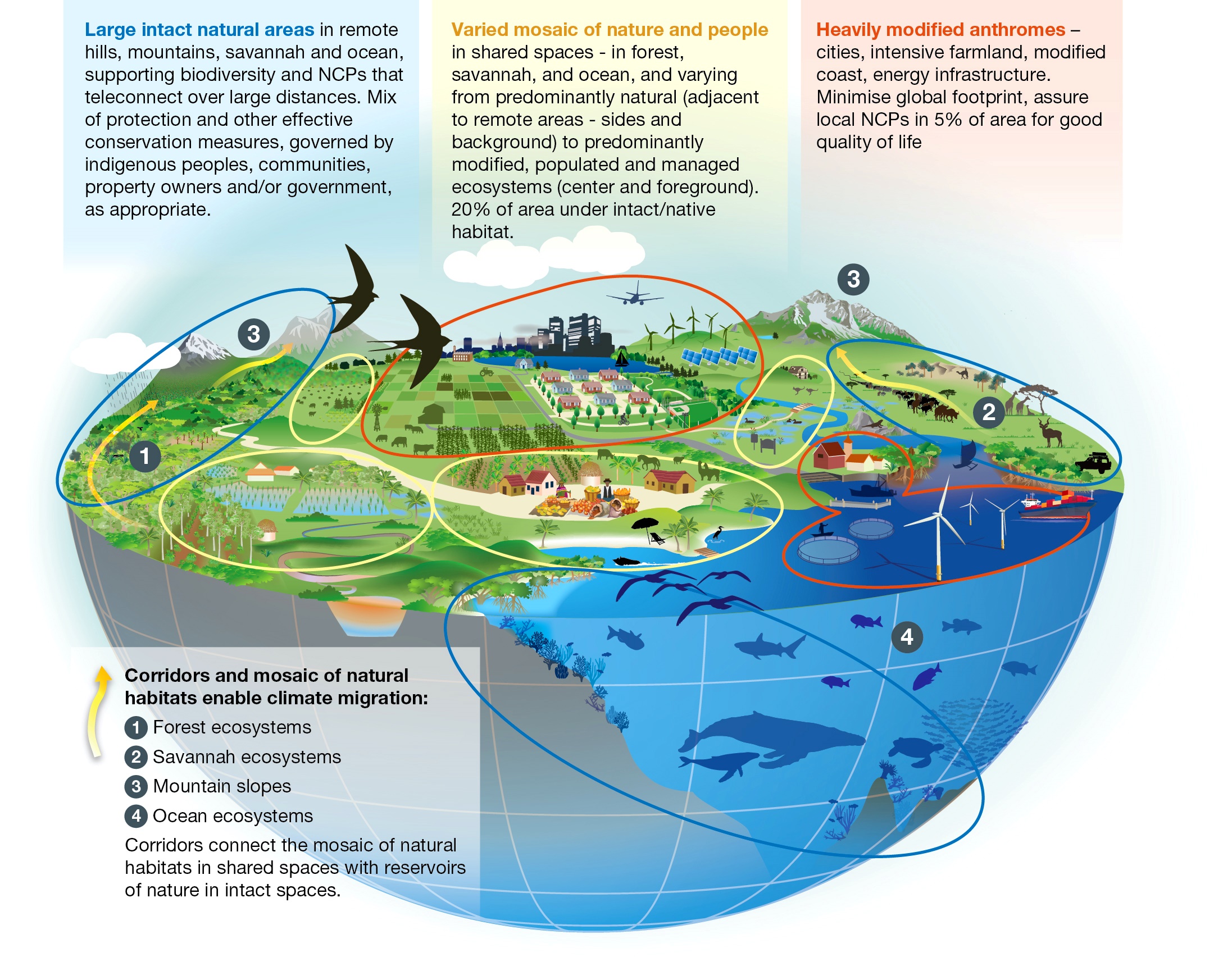

The target of 30% agreed in the CBD agreement (Convention on Biological Diversity, Kunming Montreal COP15) should be a minimum. But this objective also depends on each ecosystem. Think of the Amazon. We must protect 80% of this forest to maintain its capacity to set its own climate and water cycle, which are so important for keeping humidity and precipitation. The same applies to certain areas of the ocean which demand more protection. We need more research to identify the special needs for ecosystems to be healthy and functional, and to provide strong ecosystem services, including nature's contributions to people. Spatial planning will help us identify those areas and build a mosaic of landscapes and seascapes that serves biodiversity and covers sustainable human needs best.

How would this mosaic look like?

It consists of neighbouring spaces with different degrees of use by humans. First, marine protected areas are no-take zones; such ecosystems can unfold their natural productivity, and potential surplus productivity can then spill over to other areas where humans maintain fishing activities. Besides, migration corridors allow species to follow their needs when the environment changes, such as during warming. Finally, the zones of high-intensity uses are dedicated to higher-intensity but sustainable uses, including aquaculture and fisheries. That is the current picture that emerges. We do not just have a blackand-white situation where, on the one hand, we have highly protected areas for biodiversity and, on the other hand, heavily used areas for humans. We need a gradient with a mix of habitats where the uses can be set to adequate levels.

Multifunctional connected and structurally and visibly distinct scapes across land, freshwater, and marine biomes.

Is a new chapter opening for the oceans? The agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Agreement), also known as the “Treaty of the High Seas” was adopted on the 19th of June 2023. Is this a decisive step forward?

This treaty is closing a gap as it sets up an international mechanism for the High Seas, which are outside national jurisdiction areas. It allows us to control the situation and the practices there, parts of which have been detrimental. Too many large fishing fleets from China, Spain, or elsewhere, go there and deplete the resources. The implementation of this BBNJ agreement will be interesting to follow.

Precisely. Given the unattained objectives in terms of countries' commitment to climate change (COP 21 Paris Agreement) and biodiversity (Aichi Objectives), what can we expect in terms of implementing this treaty? Are you confident at a time when other geo-strategic priorities are taking over the ecological agenda?

I am hesitant to make a firm projection. I think the BBNJ agreement will be tedious to implement. All environmental goals that were set to date have been missed so far, and the BBNJ agreement may also be missed because of national and selfish interests. Political will is and will stay the bottleneck in all action around these questions.

However, it is essential to remember that the prime condition for a sustainable future is to respect that we cannot fiddle with the physics of the climate nor with the principles of how biodiversity and all life is maintained on this planet. These are laws of nature that we need to respect. The laws of nature are existential; they concern the foundation of our very existence on the planet. Depleting resources and destroying natural environments should be tabooed and abandoned. Many people are not yet ready to accept this reality, which is worrying. That may keep us from reaching the biodiversity and climate targets which are so important for our own well-being and survival.

We have obviously failed in our education systems to instil a sense of appreciation for how nature works, how nature is precious for us and how the life sustaining conditions of the planet can be maintained. There is a big deficiency, and it is important to reform our education systems accordingly so that the next generations including their decision makers will not have the same issues when maintaining a livable future.

Prof. Dr. Hans-Otto Pörtner

Marine biologist, former co-chair of IPCC Working Group II and member of the German Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU).

As a physiologist and marine biologist, Hans-Otto Pörtner conducted research for more than 25 years at the Alfred Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven. He is one of the world's best-known experts on the effects of climate change on marine life and beyond. As co-chair of IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) Working Group II, he made a significant contribution to the 6th IPCC Assessment Report and drew attention to the ocean with the special report on the ocean and cryosphere. His pioneering findings on climate change impacts on marine organisms have earned him worldwide recognition. Hans-Otto Pörtner is an elected member of the European Academy of Sciences and was appointed by the German government to its Advisory Council on Global Change (WBGU) in 2020. Last year, he was honored with the Planetary Health Award.

To be read also in the dossier "Seas at risk":