Keeping our Planet Alive

The sixth mass extinction is accelerating. The world’s natural balance is being profoundly altered, leading to irreversible changes in climate and ecosystems. Study after study, science is alerting us. Will we be able to prevent the decline of life? With the World Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and the 15th Convention of the Parties for Biodiversity in Kunming (COP15), the end of 2021 turns out to be decisive.

Science raises the alarm

For the past twenty years, scientists have increasingly been reporting on the subject. Resulting from collaborations and studies conducted all over the globe, they sadly converge. The verdict is unanimous: nature's already critical state is deteriorating at a rapid pace. According to the IPBES (Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services), this decline is unprecedented and, most worryingly, accelerating. Current extinction rates are at record levels: hundreds and, depending on the species, thousands of times higher than baseline rates. The researchers behind the study with the explicit title: "Endangered vertebrates, indicators of biological annihilation and the sixth mass extinction" published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) journal, explain this rush: “Close ecological interactions of species on the brink tend to move other species toward annihilation when they disappear — extinction breeds extinctions.”

As a result, one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction over the next three decades. That is, one in eight. And the count increases every year when the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) conducts a biodiversity census and publishes its red list of threatened species. Did you know that today a third of all oak trees are on the verge of extinction?

That the Amsterdam albatross is now down to fifteen mating pairs? That there are only a few years left before our beloved hedgehogs disappear from our lands?

Unprecedented impacts on our lives

Without wanting to lapse into collapsology, a clear and straightforward diagnosis is decisive as to the stakes of this trend, if it is not reversed. After all, this staggering loss of biodiversity eventually jeopardises the survival of the human population. The threat is existential. As the eminent scientist Robert Watson reminds us, "we are eroding the very foundations of our economies, of our sources of livelihood, of food security, of health and quality of life throughout the world". Professor Sandra D.az, who co-chaired the IPBES Global Assessment of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, also notes that "the contributions of biodiversity and nature to people are our common heritage and form the most important 'safety net' for human survival. But this safety net has been stretched to its breaking point.”

Remember, biodiversity is the essential foundation of our lives. In terms of food, 75% of the world's crops depend on pollination by insects and other animals. In the field of medicine, the treasures of nature discovered so far allow four billion people to be taken care of. For example, natural products make up 70% of the drugs used against cancer, not to mention that they also serve as a source of inspiration for the creation of synthetic products. In terms of climate, marine and terrestrial ecosystems represent huge storage sinks for carbon emissions from human activity. Scientists estimate a gross sequestration of 5.6 gigatonnes per year, or nearly 60% of global anthropogenic emissions. The problem is that the more the environment degrades, the more difficult it will be for the food, pharmaceutical and other industries to function.

Economic activities, sources of livelihood, health and well-being... the future of next generations and the construction of a sustainable society depend intrinsically on the preservation of the world's natural heritage. Thus, the IPBES finds that the current state of ecosystems, and the scenarios that are emerging, are jeopardising progress towards achieving 80% of the assessed targets of the UN Sustainable Development Goals related to poverty, hunger, health, water, cities, climate, oceans and land. In economic terms, this translates into heavy losses. Land degradation, for example, has reduced the productivity of 23% of the world's land surface and the agricultural production threatened by the disappearance of pollinators is estimated at between 196 and 485 billion euros.

Human activity has forced most wildlife to increase the distance they travel by an average of 70%.

A pandemic turning point

Disruptions in ecosystems present dangers that were previously largely ignored, with chain reactions that can impact human health and lifestyles. Pandemics are among these major risks. Many came to realise this with the advent of COVID-19, an event that marked a real turning point in the understanding that the health of wildlife, plants and humans are ultimately one and the same. As Isabelle Autissier, Honorary President of WWF France, sums up, "there is no healthy human being on a sick planet".

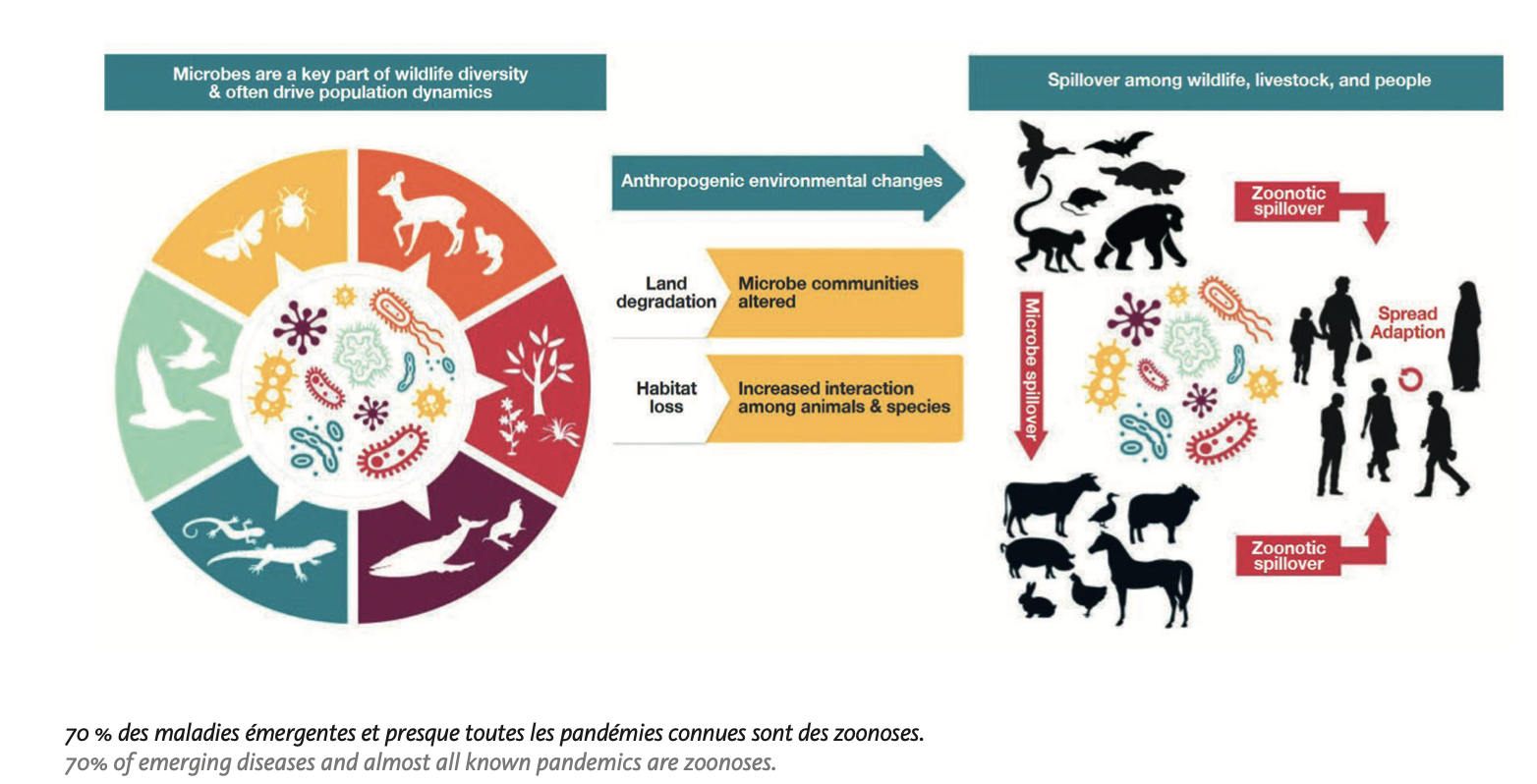

In a year like no other, scientists examined the issue to understand these close links and to qualify this concept of ''one health'' or ''global health''. In its recent report on biodiversity and pandemics, the IPBES states that 70% of emerging diseases and almost all known pandemics are zoonoses, i.e. caused by microbes of animal origin. Alarmingly, the risk of pandemics is increasing rapidly, with more than five new diseases emerging in people every year that have the potential to spread. Experts now estimate that there are 1.7 million currently undiscovered viruses in mammalian and avian hosts. Of these, 631,000 to 827,000 would have the capacity to infect humans. This is due to closer contact between wild animals, livestock and humans, which encourages the spread of germs. In untouched ecosystems, all pathogens are in their place in a fragile equilibrium, but today, natural environments are heavily disturbed by the hand of man, notably through land transformation, agricultural expansion and intensification, trade and consumption of wild species. Other aggravating factors are the excessive use of antibiotics and the exponential increase in the world's population, consumption patterns and globalised trade.

When scientists were asked how to respond to these threats to public health and the global economy, they were clear: without preventive strategies, future pandemics will be more frequent, more contagious, more deadly and even more damaging to the economy. Purely reactive strategies, with the implementation of public health measures and the race to create vaccines, are inadequate. The COVID-19 crisis has shown that this is a slow and uncertain path. It is crucial to act upstream.In economic terms, the data also speak in favour of prevention. The damage caused by pandemics is indeed estimated at more than US$1,000 billion per year. This growing amount contrasts with global pandemic prevention strategies based on reducing wildlife trade, landuse change and strengthening 'One Health' surveillance, which are estimated to cost between US$22 billion and US$31.2 billion. It is therefore time to act on this warning from Mother Nature.

This is also confirmed by the 62 scientists interviewed by Marie-Monique Robin for her book "La fabrique des pandémies" (the factory of pandemics) published in February 2021. The best antidote to the next pandemic lies in preserving biodiversity. Avoiding the 'bio-bomb' and preserving species means maintaining a protective barrier between humans and pathogenic agents in nature. Beyond vaccines and other sanitary measures, it is the answers to deterioration of the planet's natural heritage that will determine the future of humanity.

Tackling the anthropogenic causes

Factors responsible for biodiversity loss (in descending order): (1) changes in land and sea use; (2) direct exploitation of certain organisms; (3) climate change; (4) pollution and (5) invasive exotic species.

With a world population that has grown from 3.7 billion to 7.6 billion in less than 50 years, humans have literally colonised the Earth. This hasty demographic boom is accompanied by unprecedented pressure on ecosystems. A very recent study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, explains that human activity has forced most wild species to increase the distance they travel by an average of 70%. Compelled to modify their behaviour and move further away to escape human disturbance, they spend much more energy are more exposed to predators and see their reproductive deteriorated. The survival of many wild species is thus threatened.

It is mainly agriculture, but also urbanisation as well as tourism and leisure activities that are being blamed. In short, where man is gaining ground on nature. It should be noted that the urban areas have doubled worldwide since 1992 and that today more than one third of the land surface is used for cultivation or breeding. Life is being reshaped: of all the mammals on Earth, only 4% are wild and 70% of birds are poultry destined to end up on our plates. These trends are in response to population growth and global consumption, to the great detriment of forests, meadows and wetlands, 85% of which have already disappeared.

Diving underwater to look at marine ecosystems, the picture does not get much better. Scientists have noted significant degradation, with no less than two-thirds of all environments in the seas altered and only 3% of the oceans free of human pressure. The cause? Activities linked to the direct exploitation of organisms - mainly through the (over) fishing of fish, molluscs and crustaceans - and the change of use of natural environments for the extraction and transport of fossil fuels or the development of coasts for infrastructure, for example.

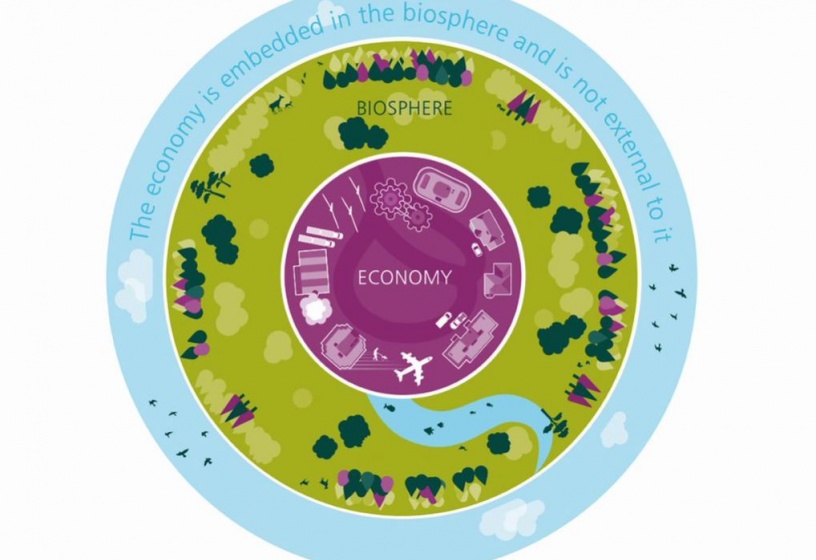

Reckless, humans have thus sought to dominate the Earth without considering that they are part of the biosphere, whose whole resources they consume. Infinite needs and a mistaken vision of a planet with unlimited resources and space have led to ever more extraction, production and processing. As a result, we now find ourselves on a highly artificial planet, made up of objects and waste that replace nature and whose mass now even exceeds the biomass. Researchers at the Weizmann Institute of Science came up with this rather telling measurement: "We find that the Earth is exactly at a crossroads. In 2020, the anthropogenic mass, which has recently been doubling about every 20 years, has surpassed the entire global living biomass". A quantitative as well as symbolic stage of the Anthropocene, the sign of an unbearable heaviness of the human being.

At least a quarter of the world's land area is traditionally managed, owned, used or occupied by indigenous people. These areas account for about 35% of the world's officially protected land area. Community conservation institutions and local governance regimes are generally considered effective in preventing habitat loss.

Source: IPBES, The Global Assessment report on biodiversity and ecosystem services, 2019.

Combining climate and biodiversity

Climate change and the collapse of life are linked phenomena that have mutually aggravating factors on a global scale. As if trapped in a spiral, they are two evils that cannot be dissociated and that must be addressed together. Take the greenhouse effect: the loss of biodiversity due to deforestation and the alteration of wetlands and marine environments means less CO2 capture, which accelerates global warming. Inversely, accelerated global warming is exacerbating the negative impacts on marine, terrestrial and freshwater ecosystems. Species lack the time to adapt and vanish.

Until now, international meetings and reports have been mainly conducted separately, but experts are gradually realising the need for a coordinated approach. The UNEP report "Making Peace with Nature" of February 2021 highlights the deep links between the issues of climate, biodiversity, land degradation and pollution. It warns against the risk of adverse effects when dealing with the topics in silos. Thus, large-scale afforestation schemes and the replacement of natural vegetation with monocultures for bioenergy supply can be detrimental to biodiversity and water resources. Similarly, the installation of solar photovoltaic plants or wind farms, which are beneficial to the transition to green energy, must be addressed in relation to biodiversity.

In this spirit, the IPBES and the IPCC, representing respectively the intergovernmental scientific platforms on biodiversity on the one hand and on climate change on the other, have started a close collaboration to address the extensive correlations that exist between their subject matter.

Biodiversity refuge, more than 35 % of all mangroves have disappeared in the last 20 years.

The COP 15 in Kunming in focus

2020 was the deadline for the Aichi Biodiversity Targets and it was an unequivocal failure. So far, actions to protect nature and conserve the countless services it provides have fallen short. But little by little, initiatives are emerging. They are adding up to paths of hope.

Experts, scientists, young and not-so-young people committed to nature, NGOs, indigenous communities, pioneering companies... The call for environmental action is increasingly resounding. The hoped-for response? That the different stakeholders, and particularly governments, make commitments that match the environmental distress for the next decade when new biodiversity targets will be set at the 15th Conference of the Parties in Kunming and the World Conservation Congress in Marseille.

There are encouraging signs on the political scene. Ursula von der Leyen, for example, calls for an international pact to preserve biodiversity and for action to be taken. The President of the European Commission is taking the first steps at EU level with two main components: the implementation of legislation to ensure that EU market demand does not lead to deforestation and the presentation of a "legal framework for the restoration of healthy ecosystems". At the United Nations, 84 political leaders - including Luxembourg - have already committed to reversing biodiversity loss by 2030 with the "Leaders' Pledge for Nature". They send a united signal to step up global ambition and take action to match the commitments needed to safeguard and restore biodiversity. Concrete and quantified measures are also endorsed, such as the Global Ocean Alliance in which 30 countries are committed to protecting at least 30% of the oceans by 2030.

Aligned actions for protecting and restoring life on Earth.

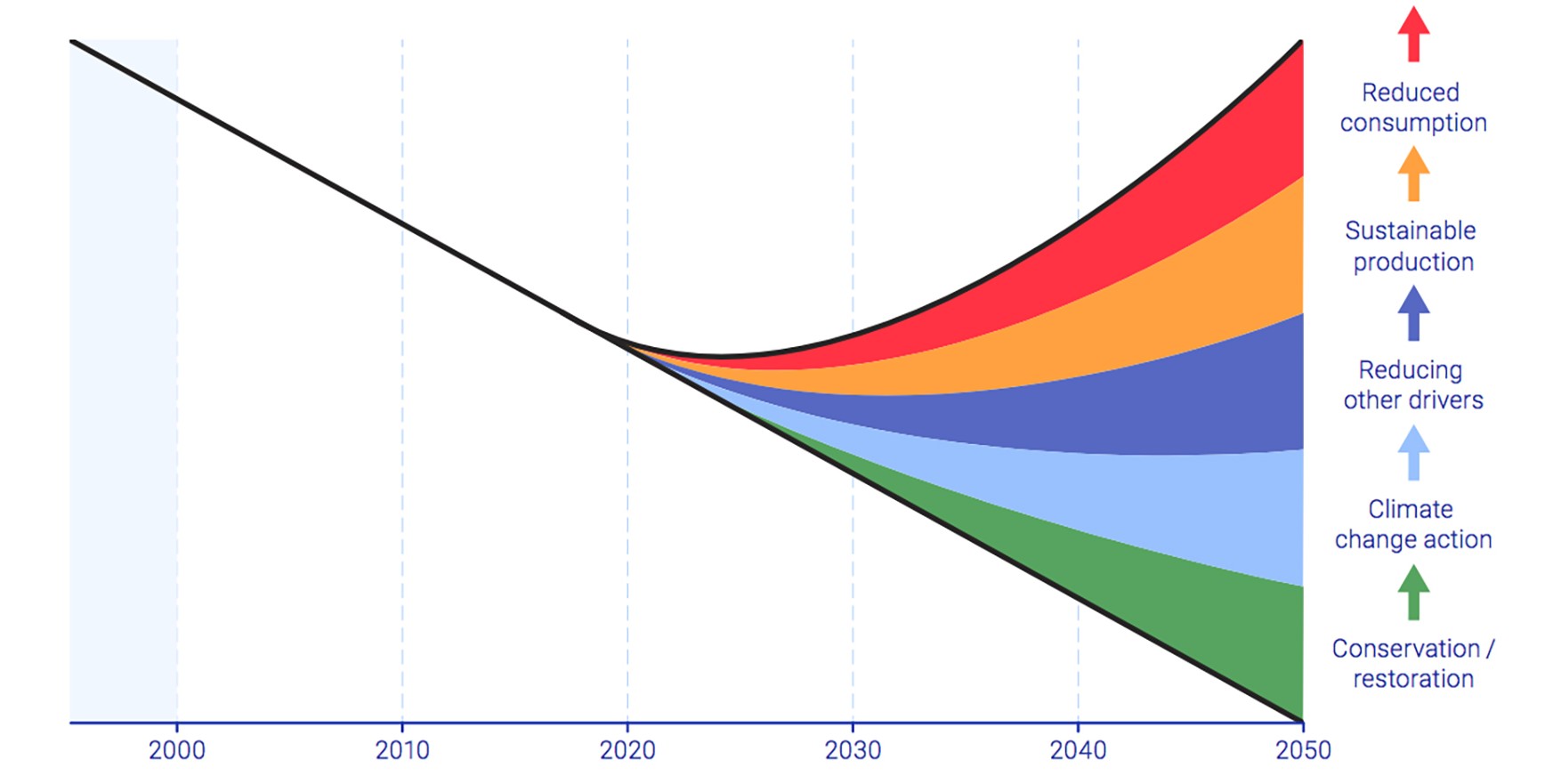

The next decade will be decisive, historic, for the future of humanity. Putting the planet on the road to recovery will require not only intensified conservation and restoration of ecosystems but also a commitment to mitigation. Agriculture, fishing, food, finance, construction, trade, tourism, mobility... a systemic and global transition of production, distribution, consumption and exchange modes is necessary. A paradigm shift called for by UNEP, which advocates an integrated package of measures that combines these conservation and restoration actions with additional measures to address pressures on natural habitats from both supply and market demand. An invitation to evolve towards a sustainable society in harmony with all the living beings that make it up. A reality for tomorrow?

Over 1/3 of the world land surface is devoted to crop or livestock production (IPBES, 2019)

of all the mammals on earth, only 4 % are wild animals.

Over 50 years, average rate on which vertebrate populations have declined.

Only 3 % of the oceans are described as free from human pressure.

70 % of all bords are poultry for us to eat.

Today, 1 million animal and plant species are facing extinction.

To be read also in the dossier "Life in free fall: no more denial?":