Reconciling Nature and Economics

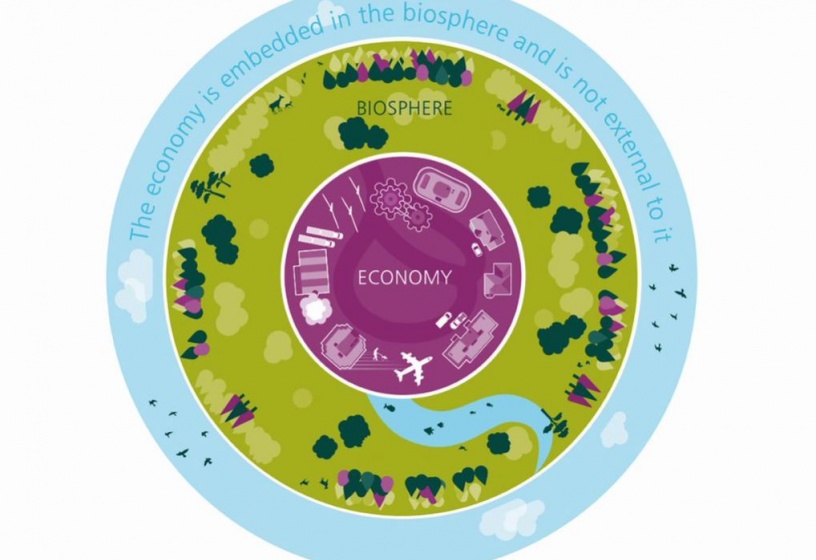

Have we ever wondered how much the life we lead, the work we do, the goods and services we consume depend on nature? The health crisis has slowed down the tempo of the economy, giving us time to reflect. Like a freeze frame, our models' flaws are more visible. The opportunity to realise that the economy is fully integrated into the biosphere, and intrisically depends on it.

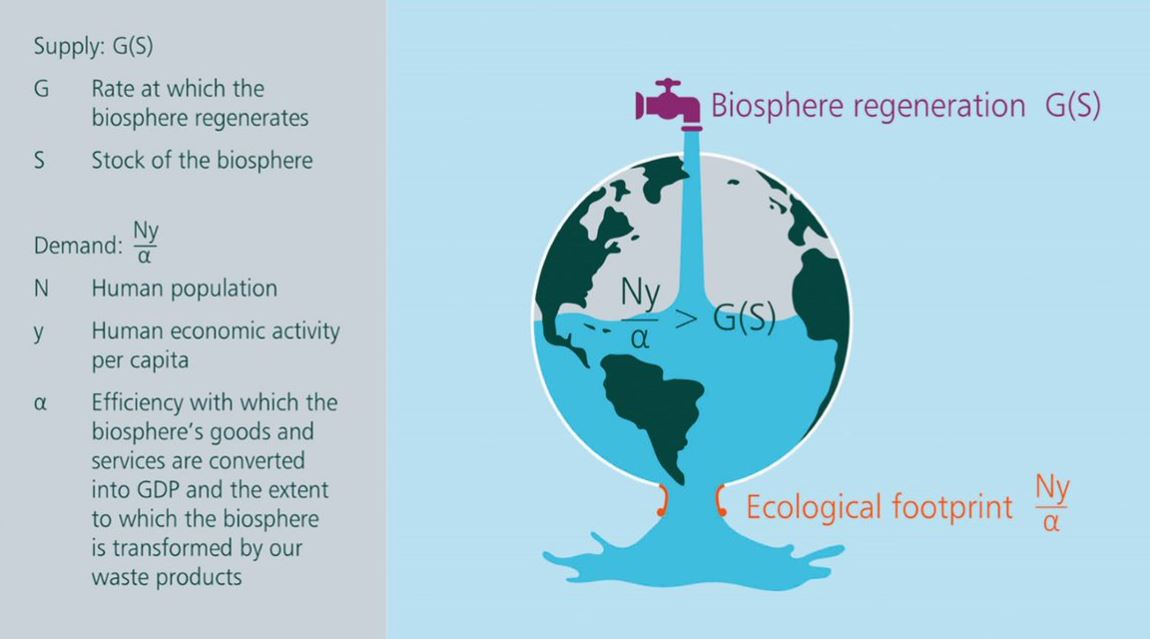

In 2021, the World Economic Forum ranks biodiversity loss and natural resource depletion as one of the five greatest risks to humanity. Published in February 2021, the Dasgupta's report on the economics of biodiversity highlights that since the industrial boom, our demands have far exceeded nature's capacity to provide the goods and services on which the global economy, our lifestyles, our health, our food, and more depend. Ecosystems no longer have time to regenerate. Resources are dwindling. And the biosphere of which we are a part is deteriorating.

More than ever, the world needs to fundamentally rethink the way society measures economic success if it wishes to stem the rapid and threatening decline in biodiversity. For organisations, this translates into a need to understand, manage and mitigate their impacts on nature, but also to begin a fundamental shift in thinking about their purpose and contributions to society. Some decide to act. They are exploring and implementing ways to do business differently, rethinking their dependencies on ecosystems and preventing threats to nature.

What is the value of nature?

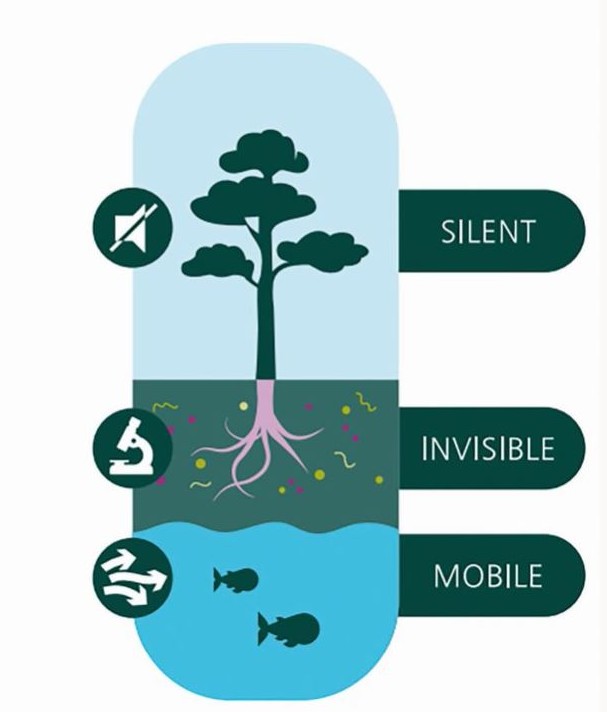

Plants, animals, insects, corals, minerals, winds, currents and tides, lands and forests, climates cradled by the seasons... Nature offers many goods and services. As a source of raw materials, energy, operating surfaces or pure air and water, ecosystems are widely used. Silent, invisible or mobile, they are often undervalued or absent from economic performance models. Yet, they are essential to ensure the proper functioning of our system.

|

Nature’s properties

"The three pervasive features – mobility, silence and invisibility – make it impossible for markets to record adequately the use we make of Nature’s goods and services. There is thus an inevitable wedge between the market prices of goods and services and their social scarcity values. This has far-reaching implications for our conception of our place in Nature. Low market prices for Nature’s goods and services has encouraged us to regard ourselves as being external to Nature" . Dasgupta Review, February 2021 |

Beyond GDP

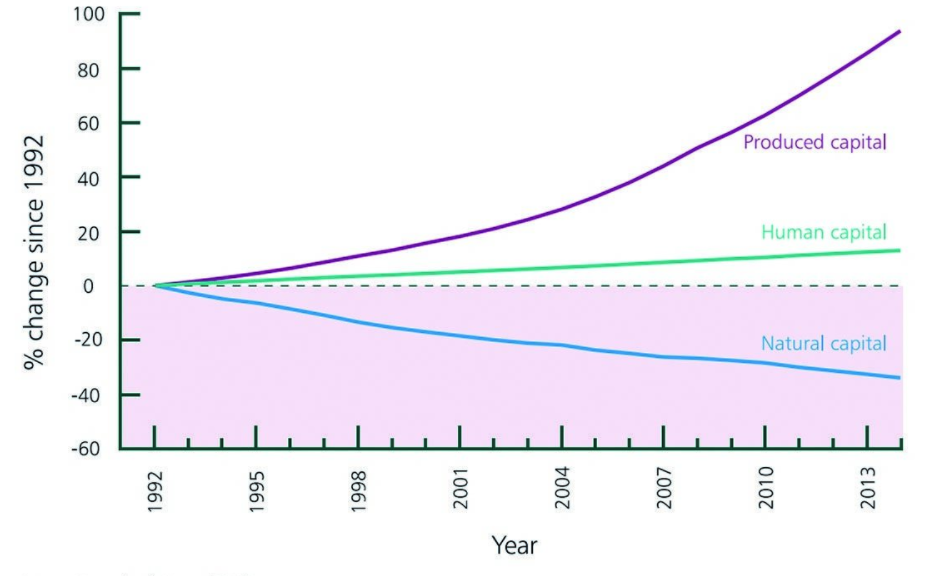

For over 70 years, gross domestic product (GDP) has been the primary measure of a country's prosperity. Yet this measure is often criticised for its omission of natural capital and its role in supporting an economy that encourages activities that destroy ecosystems and habitats essential to human survival. The Dasgupta report firmly aligns itself with this view: “The contemporary practice of using Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to judge economic performance is based on a faulty application of "economics", it underlines. It goes on to note that “in order to judge whether the path of economic development we choose to follow is sustainable, nations need to adopt a system of economic accounts that records an inclusive measure of their wealth. The qualifier ‘inclusive’ says that wealth includes Nature as an asset.” The report thus calls on society's actors to adopt a new measure to assess and secure quality of life by combining the value of produced capital, human capital and natural capital. This seems to be a necessary turnaround, as natural capital has been considerably depleted over the last decades (see figure below).

Global Wealth per Capita Natural capital per capita declined by almost 40% between 1992 and 2014, during which time productive capital per capita doubled and human capital per capita increased by about 13%.

In this respect, in March 2021, the UN adopted the SEEA (System Environmental Economic Accounting) standard allowing nations to include nature's contributions in the measurement of prosperity and well-being and thus project beyond GDP. This tool brings together environmental andeconomic information to produce internationally comparable statistics and reflect the dependencies and impacts of the global economy on nature. As a measure of the sustainable development objectives, more than 80 countries in the world – including Luxembourg – are now implementing it.

More than half of global GDP (55%) depends on biodiversity and ecosystem services.

(Source: Swiss Re Institute, 2020)

The difficult measurement of biodiversity

In response to the decline of ecosystems and with a view to prosperity, some companies are implementing new strategies that take into account the capacity of natural resources to regenerate themselves. They are taking into account the close links they have with ecosystems through the notion of “natural capital”, and sometimes right down to their accounting. As the first step is to quantify the approach, some organisations are using impact measurement, monitoring and reporting on biodiversity. These approaches help organise and highlight important information to help decision makers understand how nature influences the sustainability of their organisation. Many tools exist and are used by different sectors. The European Investment Bank uses the Integrated Biodiversity Assessment Tool (IBAT) to assess its projects. Others, such as Engie or Decathlon, use the GBS (Global Biodiversity Score). The multitude of benchmarks represents an obstacle to a global and harmonised monitoring of natural capital within the economy and companies. Actors such as the European Commission with its “Align” project or the IPBES are working to move towards standardised practices. These efforts include an evaluation of the various tools and measures available, and the development of a standardised approach to measuring biodiversity through a common reference framework.

"The demands on Nature far exceed its capacity to provide the goods and services on which we all depend. It is estimated that it would take 1.6 Earths to sustain the current standard of living of the world's population."

Changing "business as usual"

Driven by the objectives of sustainable development and environmental awareness, organisations are showing the way to transform their models towards schemes adapted to the emerging challenges of resources’ finiteness and life’s deterioration on the planet. They are redefining the company’s notions of success, mission and vision. How do they do this? By ensuring that everything they do, they can do forever. Unsurprisingly, this means overhauling a model that aims for ever more financial growth. Kate Raworth, economist and author of the book Doughnut Economics, talks about companies contributing to a harmonious planet by reminding us, in a reasoned approach, that “if something can thrive without growing, it is simply that it pulsates, that it is alive, that it creates, that it regenerates, that it is healthy”.

This is the case for Patagonia Provisions, which places people and the protection of ecosystems at the heart of the development of each of its products. For example, the brand is moving towards the marketing of mackerel with the aim of influencing consumer choices and consequently reducing the pressure on marine ecosystems linked to the fishing of larger fish such as tuna. Another example is Nicoverde, a fruit producer in Costa Rica, which dedicates 30% of its land to safeguarding forests and uses drones to irrigate its fields, reducing water consumption per hectare from 350 to 16 liters. Closer from us, Ramborn, a Luxembourg cider and fruit juice producer, has restored 1 million square meters of abandoned orchards by treating diseased trees and replanting 1,500 trees of local and sometimes ancient varieties, thus providing a healthy environment for the many species of natural heritage nearby.

Protection and restoration of ecosystems, reduction of impacts, implementation of innovations... These companies of a new kind develop activities that, while being profitable, are based on nature's needs of regeneration. And surprisingly but at the same time kind of obviously, these initiatives generally find their solutions in nature itself. By understanding it, valuing it, and sometimes even imitating it.

The decline of European meadow orchards has been dramatic over the past 100 years. In Luxembourg, the cider and fruit juice producer Ramborn has restored one million square meters of abandoned orchards.

Nature-based Solutions

Nature-based Solutions (NbS) implemented within the corporate world are cost-effective strategies that simultaneously deliver environmental, social and economic benefits. Inspired by, based on or supported by nature, these alternatives contribute to strengthening the resilience of people, the environment and the companies that apply them.

In practice, these solutions take many forms. In Bristol, Southmead Hospital has covered its roofs with plants and expanded its green spaces around its buildings. These installations provide therapeutic gardens for patients, vegetable gardens for the canteen and rainwater collection for building cleaning. This last solution has reduced water consumption by 25%. The company Hydrobox is developing small hydroelectric power plants that take advantage of running water from rivers in Africa and transform it into electricity. And in Japan, Takao Furuno bases his rice crops on the functioning of a natural ecosystem: by introducing ducks into his rice fields, he reduces the presence of parasites, provides natural fertilizers to the plants, prevents water from stagnating thanks to the birds' movements and diversifies his production with their eggs and meat.

If implemented appropriately, Nature-based Solutions can make a significant contribution to addressing many sustainable development challenges. According to IUCN estimates, for example, they can cover up to 37% of our climate change mitigation needs. These are all ways to reconcile nature and economy and move towards a prosperous future for all species. As David Attenborough summarises: “By bringing economics and ecology together, we can help save the natural world at what may be the last minute – and in doing so, save ourselves.”

Nature-based solutions are of three kinds: they rely on the innate functioning of species in their environment, develop processes made possible by natural actions, or mimic ecosystem services.

To be read also in the dossier "Life in free fall: no more denial?":