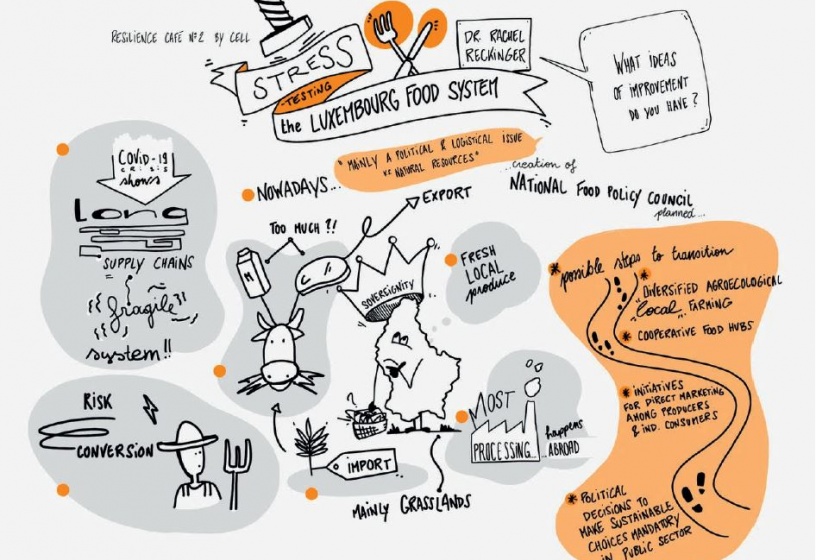

Svalbard, The World's Food Diversity Vault

If you had to store humanity’s world agricultural heritage in a safe place, where would you go? For the Crop Trust, the answer was deep inside Platåfjellet mountain on the Svalbard Archipelago above the Arctic circle. For more than ten years now, this place shelters the largest crop collection on Earth. In this interview with Crop Trust Executive Director, Stefan Schmitz, we take a closer peek at the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, a true vegetal Noah’s Ark which looks like it belongs in a fictional movie!

INTERVIEW

Sustainability MAG: The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is the largest seed reserve on Earth. How many samples do you store underground?

Stefan Schmitz: Over a million! Earlier this year, at the end of February, we celebrated the completion of the two-year renovation work in the Vault. On this occasion, seeds banks from all over the world were invited to join us and send copies of their seed samples. Over 35 depositors participated, and this officially brought us to over one million seed samples stored in the facility.

There are approximately 1,750 gene banks located in more than 100 countries around the world. What makes the Svalbard Global Seed Vault so unique?

The Svalbard Global Seed Vault is a back-up facility for these other gene banks you mention. It is not an operational gene bank, but more like a huge safety deposit box. If you picture a regular bank as we all know it, you will find safety deposit boxes where you can secure your possessions. The Vault functions a little bit like this. The big difference is that all deposits are duplicates of the original material. These duplicates remain the property of its depositor. This procedure is operated in case original collections, which stay at the depositing gene banks, get damaged or become inaccessible for whatever reason such as a war, a fire, a flood, an earthquake and so on.

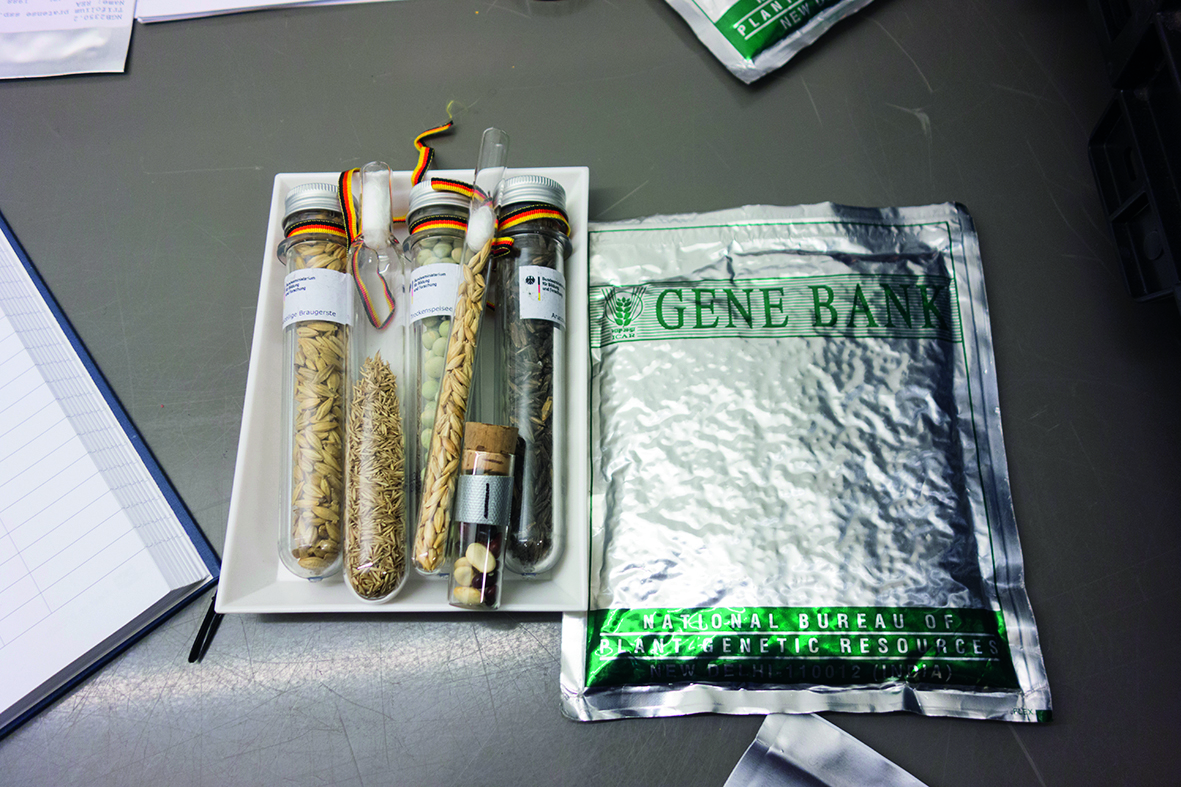

Material, like barley and finger millet, sent by the German and Indian national gene banks for the international seed deposit ceremony organised in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, this February 2020.

Has this ever happened?

Yes. One gene bank has had to make withdrawals from the Seed Vault in the context of the Syrian Civil War, where one of the world’s most important international gene banks was facing great trouble. In 2015, ICARDA, the International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas, lost access to its facility in Aleppo. Fortunately, a large portion of its seeds had already been duplicated and sent to the Seed Vault for safekeeping. As a result, ICARDA was able to re-establish its collection in Morocco and Lebanon. This case shows that the Seed Vault is doing its job. You see, before the Vault existed, there was no such insurance policy in place. Take the National Plant Genetic Resources Laboratory in the Philippines, that experienced a flood due to the Typhoon Xangsane in 2006 and a fire just six years later, resulting in irreversible losses because the germplasm was not completely backed-up.

Are the protected seeds within the Vault meant to be accessible only in case of last resort?

If for whatever reason seed banks run into trouble, they can rest assured that their seeds are safely backed up at Svalbard and retrieve them if necessary. The Vault is also a real resource for these organisations, which conserve invaluable material for feeding a growing global population. They share valuable crops for breeding more resilient varieties able to withstand the challenges associated with climate change, pests and diseases and more. The Seed Vault makes sure that they have their material no matter what. Svalbard gets a lot of attention, but it is just one part of an enormous amount of work that takes place every day and every night across the globe. Gene banks are not museums, using crop diversity is equally important as conserving it. That is why the organisations who have stored their material in the Seed Vault, make their crop collections available to breeders or research institutes to help make our crops more resilient to agricultural challenges.

So, we are talking about an open-source philosophy serving a common good?

Exactly. The Seed Vault was established with the principle that all seeds are a global public good. For an institution to send seeds to Svalbard, it must first sign a depositor agreement, which ensures the seed samples are unique, important for food and agriculture, safety duplicated at the second level and made available to breeders and researchers. It is this open collaboration that makes the Vault very special and efficient to ensure humankind has the available resources to feed the world in the 21st century.

Eggplant varieties and wild relatives fruits.

The globalised food system is being seriously questioned at the moment. How can we move towards greater resilience?

Covid-19 has revealed in very stark terms the vulnerability of humanity. It is too early to say how exactly the food system will be impacted in the long run. However, looking at the post-crisis, we already see tendencies that this highly over integrated food market might turn out to be a real bottleneck for feeding the world. I believe that it is time to carefully rethink globalisation to mitigate the effects of future shocks of the kind we are currently experiencing and to allow us to bounce back from them. We cannot avoid nor abolish a global food market, that is not the point. But we need far more diversity and regionalisation for many different reasons.

One is evident, as it just turned out, that the distance between the producer and the consumer can be highly vulnerable. Another one is that promoting agricultural systems in rural areas represents a great chance to create resilient provisioning food systems that rely on local markets. Everybody would benefit from this. But to tap this potential, you need far more locally adapted seed resources.

We are talking here about varieties adapted to a specific climate, a particular soil and so on. And when you start rethinking globalisation, the trade regime, the strengths of a local agricultural system, this is where all the materials conserved in the world’s gene banks come into play and help provide the diversity of seeds needed. Strengthening our food systems won’t be simple. There are many answers and no silver bullets. No solution on its own will be sufficient. But nothing will succeed if there is no crop diversity to work from.

The advent of a so-called modern agriculture has seen the gradual replacement of traditional varieties with commercial seeds, resulting in plants standardisation and yields optimisation. In what sense does this shift represent a danger for food security?

While change is inevitable in farming systems, as farmers experiment with and adopt new crops and varieties, this narrowing of crop diversity has consequences for the productivity, stability and resilience of the global agri-food system. We have in the past decades pursued an intensification of our agricultural systems that has helped to feed the world, but that has come at an environmental price and may not be sustainable as there are still two billion people who are malnourished, and of these, about 749 million who do not get enough calories.

In the long term, narrowing crop diversity will do no good. Our food systems are too vulnerable to changes, to pests and diseases and to changing environmental conditions. I am convinced, and that is also what Crop Trust stands for, that the diversity of seeds, of food, of diets, of agricultural practices, and diversity as an overarching principle is absolutely important. We must rethink our global food system and work towards greater diversification in particular in times of climate changes. It is key to small agricultural holders as it enables them to adapt to various changing conditions: environmental, social, economic conditions, demands coming from markets… There are so many reasons that agriculture and biodiversity have to come together!

Talking about biodiversity, what do you think is the main threat to it?

One of the most significant threats to biodiversity has been agriculture itself. Even without climate change, a lot of biodiversity was lost as agriculture developed. Traditional crop varieties and their wild relatives disappeared from farmers’ fields and forests, cast aside in favour of genetically uniform, potentially high-yielding types or victim to resource degradation, destruction of habitats and shifting ecosystems. Today, crop diversity remains at risk for many of the same reasons but also due to lack of investment in gene banks and in the institutions that safeguard this material. At the same time, climate change is becoming more and more critical. We will have to find solutions to adapt to both of these threats simultaneously. More awareness needs to be raised.

How do gene banks represent an efficient weapon against climate change?

The public often does not realise this, but there is so much work going on in developing more climate-resilient crops. This requires seeds to be sent out every year to help breeders and research institutes around the world make progress regarding climate-resilient food. Take wheat. To adapt to higher temperatures, breeders must go back to the 125,000 varieties of grain stored in the world’s gene banks to search for the maybe only one type that can withstand a hotter climate. International collections of crop diversity distributed last year over 66,000 seed samples to users around the globe.

In the context of climate change, you also pay particular attention to wild seeds. Why are they so important?

Agriculture started with wild plants and grew from there. For millennia, farmers have been domesticating, selecting, exchanging, and improving food plants in traditional ways, within traditional production systems. Meanwhile, many of the wild relatives of these crops have persisted in nature, adapting to harsh environments. Now, as humankind is trying to figure out how to find varieties that are more tolerant to climate change conditions, the solution might lay in the genes of wild crop relatives. They tend to be more robust than their high-yielding domesticated counterparts. Genes for drought-tolerance, for example, have been identified in the wild relatives of tomato, chickpea, barley, rice, and wheat.

Is there a limit or can the Vault store all types of plants that exist on Earth?

Svalbard can store many seeds, but not all of them. These exceptions include favourites like banana, cacao, cassava, coffee, potato, coconut, tea, apples, and others. That’s because some of these crops do not produce seeds at all. Others produce seeds, but the resulting plants do not always resemble their parents. That’s a problem because when you conserve something, you want to be sure of what you will get if you ever need it again. All these plants need alternative methods for conservation. This is usually done by growing seedlings in jars or test tubes, known as in vitro conservation, or outdoors, in what are called field collections. These methods effectively place the crops on permanent life support: they need regular human attention, and are prone to natural disasters, pests and diseases.

Lately, there is another way that is growing in popularity: cryopreservation. This is the process of conserving plant samples in liquid nitrogen at a temperature below -80°C. For this alternative conservation strategy, Svalbard is not suitable. There are other smaller gene banks taking care of this. Discussions are currently being made to create a global vault for these types of plants too.

The Crop Trust recently celebrated its 15th anniversary. What are your ambitions for the next fifteen years?

I dream that in 2035, we will have all the unique crop varieties in the world important for food and agriculture safely backed up in the Svalbard Global Seed Vault and that we will have the funding needed to secure the world’s most important crop collections for a very, very long time. The Crop Trust was established just over fifteen years ago with a mission to help build a global system of crop diversity conservation and use and fund it through an endowment that would make it a lasting reality. Extraordinary changes have been accomplished in just 15 years. If I look to the future, I am hopeful we will complete our global task.

To do so, my science colleagues tell me that Svalbard should host a volume of about 3 million samples. The time and resources this task will take are finite, well understood, and within reach, but we need the support of everyone invested in the food system to make this a reality.

What actions can Luxembourg concretely take to support your initiatives?

We need people in every country to speak to their governments, urging them to contribute to the endowment fund and support international action for a shared resource that no country can do without, and no country has enough of. We need foundations, private companies and individuals to join us in imagining an effective, efficient global system for safeguarding the basis of our food, and, most importantly, making it a reality. Funding crop conservation efforts are essential because food security is not a five year or a tenyear goal, but a forever one. I would say that helping to feed the world is an excellent investment.

Constant seed storage temperature in the Global Seed Vault

Samples in the Vault

Varieties of crops that can be stored in the Vault. Each sample contains on average 500 seeds, so a maximum of 2.5 billion seeds may be stored in the Vault

To be read also in the dossier "The Food To Come":