Some Reflections on the Resilience of Luxembourg's Food System

Tribune of Rachel Reckinger

"

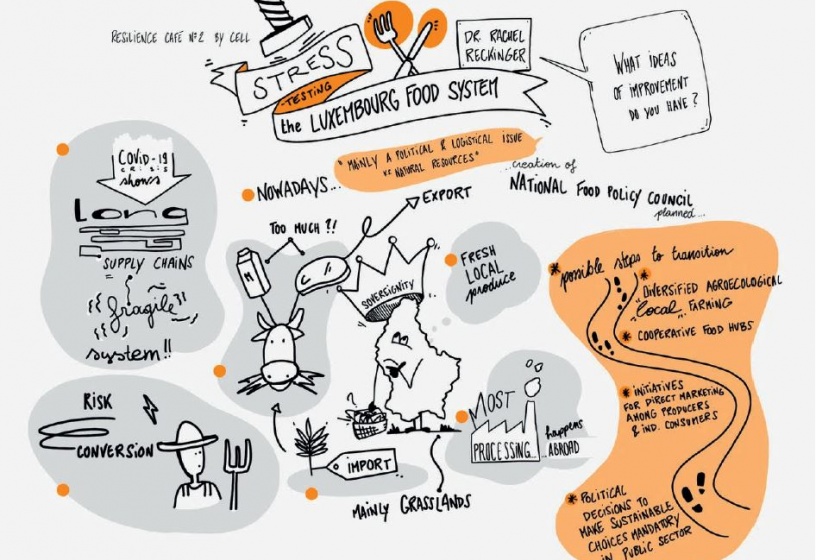

Moments of crisis like the current one sparked by Covid-19 engage social, economic, cultural and political institutions of a society, and stress-test their resilience. In such times of upheaval, individual and collective food supplies become primary concerns. How resilient is Luxembourg’s food system when international supply chains are disrupted? Which vulnerabilities transpire, even in the wealthiest of Western European food-secure countries? The rapidity with which borders closed, even inside the Schengen space, draws focus to national performances and the question of food sovereignty.

Food sovereignty is characterised by the largest possible diversity of locally produced food, and by the highest degree of autonomy possible from international imports and transportation through local options, in a context of food democracy ensuring equity and participation.

Luxembourg is predominantly a grassland region, lending itself to cattle grazing – only ruminants can make grass ‘edible’ to humans – even though a remarkable diversity and density of vegetable production is possible on comparably small surfaces, but requires higher workforce and watering infrastructure. Agroforestry (combined crops between trees, pasture and domesticated animals) is still rare in the territory. In terms of food selfsupply ratio, Luxembourg produces 114% of its beef needs, 99% of milk, 67% of pork, but only 35% of eggs, 3-5% of vegetables, 1,4% of chicken and less than 1% of fruits. As for processed foods, the vast majority of goods are imported. Though this is changing, the processing system today falls short of national demand.

As a small country, Luxembourg would be suitable for shorter supply chains and could adapt to changing circumstances, but only if the food supply is steady and diverse. On the one hand, small producers experience fluctuation and cannot consistently guarantee supply to corporate clients. But cooperative-run platforms or food hubs grouping a number of small producers could function as a one-stop-shop for wholesalers. On the other hand, larger companies in Luxembourg already offer commercial partnerships to national producers who agree to invest in missing products or production lines, but these initiatives would benefit from a market stretching across the Greater Region and beyond – going beyond nationalistic and protectionist understandings of regionality. Current research shows that apart from fish, chicken and tomatoes, all product categories are already being produced in sufficient quantity in the Greater Region to surpass the Greater Region’s out-of-home-catering sector’s needs. Yet, only a minority of these products are currently served locally – indicating that food sovereignty is mostly a logistic and political issue of supply chain management, market orientation, price policies and national legislative regulations.

Experts also point to the need for an agricultural model based on diversified agroecological systems, reducing external input, optimising biodiversity and stimulating interactions between different species as part of holistic strategies to build long-term fertility and secure livelihoods. Yet, Luxembourg lacks the labour capacity for such a transition to more resilient systems, where knowledge-pooling is key. If there were more market incentives and political warranties for farmers, such undertakings would be less risky.

As high-quality, ethical and sustainable local food is made available and becomes the norm, consumers will develop more sensitivity for local contingencies, ethical and high-quality, organic food, seasonality, etc. State-run labels that certify various types of quality enhance food literacy and more sustainable purchases within private households or procurement behaviour among public buyers, only if they are transparent about added value and backed by laws that make such criteria mandatory. Thus, stringent and encompassing governmental action of democratic and accountable governments could act as a lever in transitions to more resilient and sustainable food systems. Such conditions are then ideal for a deliberate shift towards effective multilevel governance of food systems. Social movements, entrepreneurs and civil society can innovate and bloom. As success grows, emerging local food initiatives can move in from the margins and engage with formal legislative processes at national and EU level. A Common Food Policy could prioritise ethical and sustainable experimentation through complementary actions and coherent food policies at EU, national, and local levels. Food Policy Councils are recognised innovative and efficient tools for multi-scale food policy and governance.

To meet these challenges, Luxembourg is currently founding the first Food Policy Council on a national level, as a multi-stakeholder platform for independent cooperation among equal partners from the three sectors of Luxembourg’s food system: policy and administration; research and civil society; production, transformation, gastronomy and trade. This initiative aims to serve a system that is socially just, ecologically regenerative, economically localised and engaging a wide range of actors. It seeks to ensure high-quality, ethical and sustainable food security for its entire population by shortening supply chains in a (trans)regionalised and cooperative way.

Food sovereignty is thus increasingly based on local diversification, innovation, and collective learning processes. Because of its small size and its unique multi-cultural population, Luxembourg can provide a favourable site for experimentation with sustainable innovations at local or transregional levels and build a multi-stakeholder-lead effective food policy. It then can use its political and economic international weight to push best practices forward.

"

For more details, check out https://food.uni.lu

To be read also in the dossier "The Food To Come":